ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

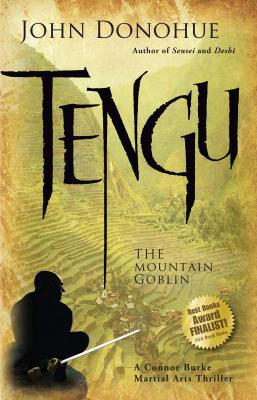

Tengu. John Donohue

Читать онлайн.Название Tengu

Год выпуска 0

isbn 9781594391538

Автор произведения John Donohue

Жанр Ужасы и Мистика

Серия A Connor Burke Martial Arts Thriller

Издательство Ingram

He grabbed me and did the hip shift. I just extended my right arm through him, following his movement. His atemi shot out quick and crisp, a blur on the periphery of my left side. It was a good serious blow and I would have seen stars if it had connected. I liked that about the guy—he was doing this as hard as he could and had enough respect to know that I was capable of dealing with it. It was a shame what I had to do next.

The whole point of the demonstration was to reveal how inadequate his technique was. It’s a hard thing to do to someone who’s probably got over a decade invested in the move and the system that spawned it. But Yamashita is not in the illusion business. He believes in the underlying unity of everything that’s effective and exhorts us to meld functionality with esthetics. Sometimes the result is as graceful as the swoop of a bird. Sometimes you are as subtle as a train wreck, but always your opponent should be the one left in the rubble.

The godan was used to dominating people through superior grace and technique. He wasn’t used to someone like me. He shifted to draw me off-balance and I drove in to join him. The hand he tried to immobilize loosened its hold on his collar and sought his neck instead. His diversionary strike was hard and fast, but I slammed it away with my left forearm, and I saw the quick wince of pain tighten the skin around his eyes.

That flash was all I needed. I struck him a few times—a chop to the neck, a wicked elbow jab to the solar plexus. It happened too fast for me to bother to register. Then I was behind him, and I strung him out and dumped him hard on the floor. In the real world, you give the shoulders a little English as they go down—it makes the head bounce when it hits. But he was new to Yamashita’s school and I tempered my throw with a touch of mercy.

He could fall pretty well, but the thud still echoed in the room. Outside in the murk, thunder rolled in mocking imitation. I came around to the godan’s side and looked in his eyes to make sure he was okay. They focused on me all right, and the look on his face was not pretty. I gave a mental shrug and helped him up. To survive in this dojo, you must learn to let go of some pride—no hard feelings, just hard training.

Yamashita glided up to us. “So. To assume a technique will work is to provide your enemy with a weapon to use against you. I have made Burke do this thing,” my teacher turned to look at the class, making sure that the point he wanted to make was heard. Many of them were eyeing me warily. “In time, you will come to know him. His technique is . . . ” he waved a hand as if to show what had just taken place, “as you see. But he sometimes holds back and does not push hard enough.”

His students, I thought, or himself?

“Burke is a humane man,” Yamashita continued. “It is a great gift. But each of us needs to balance mercy with . . . efficiency. The proportions are mixed differently in each of us. And we struggle for balance. Listen to him. Train well. Ultimately, you will find him a good teacher.” Then he looked at me, his eyes dark and glittery in the lights, like the flash of stormy weather that was held at bay by the dojo walls.

“You must push them, Burke,” he told me.

“Yes, Sensei,” I bowed.

By the time class had ended, night had arrived. The rain came in waves, the distant drumming echoed in the murky night. Yamashita and I went up to the loft portion of the dojo where he had his living quarters. The training floor below was dark, and the soft lights from upstairs gave you a sense of warmth and comfort.

My sensei left me in the sitting area. I heard water running as he filled a pot. “I will make something hot to drink,” he called to me from the kitchen. “I have a new blend you will like.” I smiled to myself. Coffee was one of Yamashita’s obsessions. He was like a mad alchemist and fussed over the process of brewing with all the attention and precision he brought to life in general.

“Where’s it from this time?” I called. Last Christmas, I signed him up for monthly deliveries of something they called “new kaffe.” So far, we’d sampled the produce of Jamaica, Madagascar, and a variety of other places that Yamashita delighted in pinpointing with the aid of a huge hardbound National Geographic atlas. He sits with the atlas splayed across his lap, stubby fingers tracing the contours of the countries in question. At those times, he looks like a happy child.

“Peru,” he answered when he finally came in. He set a square wooden tray down and poured me a cup. It was an act of courtesy and hospitality on his part. I had come to look forward to the ritual. My teacher would invite me up. We would drink coffee, letting the smell and the steam wash against our faces. And I would see another side to this complex man.

I looked at his cup. There was a tea bag in it. “You’re not joining me, Sensei?” It was unusual.

He smiled tightly. “This evening, Burke, I have a desire for something soothing.” He picked up a spoon and fished the bag out. I could smell the mint.

“Is something wrong, Sensei?” I remembered the transient glimpse of trouble I had seen earlier in his usually stoic face.

Yamashita sipped at his cup, his eyes almost closed. He set the cup down and sat back, hands on his stomach. Then he looked at me. “I wonder, Professor,” he replied, pointedly ignoring my question, “how the godan felt about the lesson you gave him?”

I shrugged. “He probably wasn’t too happy. But you were right. It needed to be done.”

“So,” he said and sipped at his tea again. “As a teacher, it is difficult to know when a student is ready to hear something, neh?” I nodded in agreement. “This is perhaps one of the hardest things to gauge.” He held up a thick hand and balled it into a fist. “When to give,” he opened the fingers of his hand toward me, “and when to withhold,” the fist formed again.

“How do you know when the time is right?” I asked my teacher.

He smiled. “Sometimes, you sense it. Or see it in a student’s movements.” He looked at me for affirmation. I nodded. We had both experienced this with trainees. Then Yamashita smiled. “Other times, you guess.”

“Do you think he was ready for that lesson?”

“Time will answer that question,” he said. Then he grew solemn. “Time . . . ” he said, and appeared ready to go on, but the phone interrupted him. I got up and went to answer it.

“Hello?”

“You makee lice?” a screechy voice demanded.

“What!” I said, momentarily flustered. Yamashita looked up inquiringly at the tone of my voice.

“Yeah,” the voice continued, “I’m interested in kung-fu lessons.” Then the evil cackling started.

“You idiot,” I told my brother Micky.

The voice on the phone became normal, more recognizable. “Yeah, well, I tried your apartment and got no answer. I figured you’d be there.”

“What’s up?”

“You comin’ tomorrow?” Micky asked. It was his wife Deirdre’s birthday and the entire family would descend on his house like a cloud of Mayo locust.

“Wouldn’t miss it,” I told him. “Why?”

“No reason,” he told me pleasantly. Which was a lie. Micky was a cop and when he asked questions, it was for a reason. His conversation had all the subtlety of a chain saw. I promised I’d be there and we hung up.

“Your brother the detective?” Yamashita said. His eyes glittered in the lamplight. I nodded. “He wishes to see you,” he stated in reply. It was not a question. He sat there quietly, watching me.

I lingered over the last of the coffee, but Yamashita never picked up the thread of the conversation that had been interrupted by Micky’s call. I knew my teacher well enough to know that it wasn’t that he had forgotten, rather that he did not wish to pursue it right now. My sensei doles out knowledge on