ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

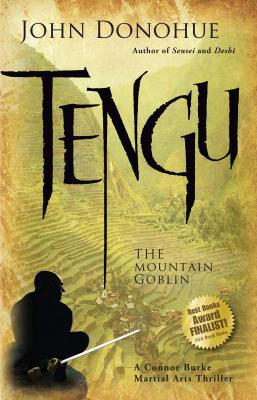

Tengu. John Donohue

Читать онлайн.Название Tengu

Год выпуска 0

isbn 9781594391538

Автор произведения John Donohue

Жанр Ужасы и Мистика

Серия A Connor Burke Martial Arts Thriller

Издательство Ingram

But Yamashita’s dojo is a place where you get what you need, not what you want. He himself is a bit of a surprise. Asian, but not wispy. He’s a dense howitzer shell of a human being. He prowls the practice floor like the burly predator that he is. He speaks in an elegant, curt manner with a precise pronunciation that many of his more senior students unconsciously begin to mimic. His hands are broad and the fingers thick, his forearms corded with the strange muscles of the swordsman. So I didn’t feel bad that the novices thought I was decidedly second-string. Standing next to my teacher, most people are.

These new students were from various aikido schools and, while it’s a nice art, like most systems of fighting it conditions you to do some things extremely well and to do other things not at all. They were all yudansha—black belts—and were skilled at the techniques of their system. Some came from the mainline aikido schools that were still connected to the founder’s family. A few were from the harder variants promulgated by disciples who founded their own styles of the art. They all had the fluid movement and propensity for direction shifts and other disorienting moves that would let them dominate an opponent. Executed well, these techniques are effective. But the process of learning them, of repeating the same pattern over and over, of dealing with a choreographed response and a looked for result, creates a type of mind-set that Yamashita detests.

People, as my master has taught me and my experience has proven, are unpredictable. Our techniques are grounded in the commonalities of movement and possibility inherent in the human form, but there are always surprises out there. No matter what you expect to happen, you need to stay open to the possibility that things may not turn out exactly as you planned. It’s a commonplace insight, but one that needs to be absorbed deep into your muscles, because to overlook it is to court disaster.

I had worked with the students on some variants of a very basic technique they knew as ikkyo. It’s a defense to an attack that can come in different forms—a grab or a strike—but that ends with the attacker immobilized through an evasive maneuver that unbalances and distracts the opponent, leading him to a point where the joints are manipulated into an angle that violates normal human kinesiology and he’s subdued. With students at this level of proficiency, the action is smooth and fast. Partners flow in a blur, swirling into the inevitable success of the technique. It’s great, as long as the attacker cooperates.

But what if he doesn’t?

I knew only too well that a desperate opponent will do the unexpected. The white scars I have on my hands are a fading reminder of a skilled lunatic who almost took my life. The fear and pain of that battle sometimes returns unbidden late at night and I am haunted by the memory of rain and death on a wooded mountain.

I was trying to impress upon the trainees the importance of real focus and a more elusive quality called zanshin. It means “remaining mind,” and different teachers use the phrase in different ways. For Yamashita, zanshin is the quality that preserves you from losing sight of the unpredictability of life— and of your opponent. We train long and hard to focus on an attack or a technique—to give it everything we’ve got. But the effect of zanshin is the development of an awareness that is both inside and outside the moment. Commitment with flexibility. Balance while flustered. Creativity in chaos.

When my students started to flow into their ikkyo routine, I continually encouraged them to stay grounded in the technique, but not to lose themselves in it. It sounded contradictory even to me. The point I was trying to drive home was that they shouldn’t be so confident in what they did. They needed to stay alive to the possibility that the opponent would not respond as they had come to expect, that the opponent wouldn’t lose focus or balance, or flinch from the distracting atemi blow that was intended to set up the technique. It was hard to get through to them. They were more confident in themselves than they were in my ability to show them something new.

Yamashita finally called the group to order, seeing that alone I couldn’t get the point across.

He regarded the class. They sat quietly; a few mopped sweat off their brows with the heavy sleeves of their keikogi. Many of them had just gotten the dark blue practice tops Yamashita has us wear. They are dyed a deep indigo and when new, the coloring comes off on the skin. I watched the students and smiled inwardly as they created faint blue smudges on their faces. It was a rite of passage we all experienced during our first months here.

Outside, a gust of wind pushed against the building—you could feel the subtle change in air pressure. Winter was upon us. Yamashita’s head swiveled to take in the sitting row of novices. His thick hands lay in his lap, palms up and fingers curled slightly, dangerous looking even in rest. He spoke quietly and you had to strain to hear him over the sound of the rain on the roof.

“When we train,” he said, “we must strive to go . . . beyond ourselves. To see more than what lies on the surface. So.” He gestured with one hand and rose to his feet. He stood in the hanmi ready posture familiar to these aikidoka. “Familiar technique is a good friend, neh?” He flowed in a swift pantomime of the actions in the ikkyo technique. Immobilization of the attack with the left hand—a hip twist to off-balance the attacker—the distracting blow—then the finish, as smooth and certain as the downward flow of a current. He finished and looked at us. “But if you lose yourself in the technique, you . . . ” he brightened as he came up with the finishing phrase, “ . . . lose yourself. Do you understand?” Some heads nodded hesitantly. Others frowned to show him that they were thinking.

Yamashita looked about and sighed. “Sometimes what appears to be our friend can be our enemy. To be so certain that a technique will succeed is to court disaster.” He looked eagerly about at the class. They had all been training for years in various dojo. Maybe that was the problem. Some schools were tougher than others, but they were all schools. People tended to cooperate with one another. It cuts down on injury and made sure that everyone could make practice again next week. But it wasn’t real fighting. The whole point in real fighting is to make sure that the other guy doesn’t make practice next week, or maybe ever again. And that’s a hard lesson to teach someone.

“So,” he concluded and gestured to me. I stood up with an inward sigh. Serving as my teacher’s demonstration partner is a regular part of what I do, but it does induce high degrees of wear and tear and I’m not getting any younger. But today I got a reprieve. Yamashita gestured again to another student, a godan—fifth degree black belt—in aikido who had some of the most fluid moves we had seen that day.

“Ikkyo,” he ordered. He didn’t bother to identify who was attacker and who was defender. We were all experienced enough to know that the junior member always defends. Which meant that I would attack. We set ourselves and I looked for a brief moment at Yamashita, trying to figure out what exactly he wanted out of me for this demonstration.

He looked right back at me and his glance was the same cold, severe look he gave everyone on the dojo floor. “Take the middle way, Burke,” he told me.

My teacher is not someone who believes in making things easy.

The whole thing works like this: The attacker reaches out with his right hand and grabs the collar of the defender. So I did, and the godan flowed right into the routine. He grabbed my wrist with his left hand while swiveling his hips so as to pull me forward and off balance. Then his right hand came around to smack me in the head and distract me, which should have set me up for the technique.

It’s based on a simple premise: it’s difficult to stay balanced and centered when threats are coming from either side of you simultaneously. The conventional wisdom is that you either opt to stay upright or block the strike, but you don’t do both. At least most people don’t.

But Yamashita