ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

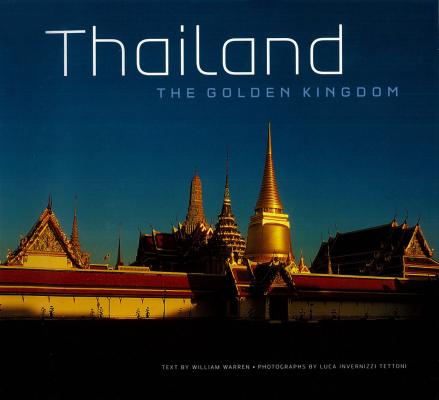

Thailand: The Golden Kingdom. William Warren

Читать онлайн.Название Thailand: The Golden Kingdom

Год выпуска 0

isbn 9781462909391

Автор произведения William Warren

Жанр Книги о Путешествиях

Издательство Ingram

Thailand's revered monarchy has managed to adapt itself to demands of the contemporary world without losing its rich traditions and ceremonial grandeur. Also still vigorously alive are other memorable parts of the old cultural fabric: enduring faiths (Buddhism most prominently, but others as well); an internationally celebrated cuisine; sports (try an evening at Thai boxing to discover how different that is); and an almost endless array of festivals, rituals and classic arts found nowhere else.

"Amazing" is the word selected by the Tourism Authority of Thailand to sum up this diverse land. And amazing it most certainly is-full of beauty both natural and man-made, full of serendipitous surprises. It is a country that constantly draws its visitors back to discover yet another part of its complex pattern.

A young classical dancer; the elaborate jewelled costumes, inspired by court dress during the Ayutthaya period, are works of art in themselves.

Aspects of Thai life.

Thai boxing, a sport that involves grace as well as ferocity.

Buddhist monks meditating in a field.

Elephants in the famous roundup held annually in Surin province.

Dancers in traditional costume.

A procession carrying lustral water during the northern Songkran festival.

Members of the Royal Guard taking part in the Trooping of the Colors in Bangkok.

Students learning the classical dance gestures.

Members of the Akha hilltribe gather for a festival.

History

"When the Waters begin to retreat, the People return them Thanks for several Nights altogether with a great Illumination, not only for that they are retired, but for the Fertility which they render to the Lands. The whole River is then seen covered with floating Lanterns which pass with it... Moreover, to thank the Earth for its Harvest they do on the first days of their Year make another magnificent Illumination..."

— Simon de la Loubere, A New Historical Relation of the Kingdom of Siam (1691)

The gold handle of a sword that forms part of the Royal Regalia.

Painting in the throne hall of the Chakri Maha Prasat, showing Sir John Bowring being received in audience by King Rama IV in 1855.

The earliest inhabitants of what is today Thailand are known only in shadowy form, through the assorted tools and ornaments they created. Some of these have been found in Kanchanaburi Province, along the River Kwai, others elsewhere in the country. The most dramatic discoveries came in a tiny hamlet called Ban Chiang in the northeast. Here, from around 3600 BC to 250 AD, an enigmatic people not only cultivated lowland rice but practised the art of bronze metallurgy, at a time much earlier than previously suspected. They also lived in houses, wove textiles, had domestic animals and fashioned objects that showed a refined sense of beauty.

The origin of these people remains a mystery. So does their fate, though some experts suggest they may have been the first of a series of migrant groups who were attracted to the fertile Chao Phraya valley and river basin. Two of the most important arrivals here were the Khmers and the Mons. Khmer culture reached its culmination in the splendors of Angkor, in the 12th century, but they also established cities deep in present-day Thailand. The Mons founded the Dvaravati Kingdom in the western half of the Chao Phraya valley and produced some of the earliest Buddhist monuments; their ancestors still live in the area.

The Thais, who would become the predominant group, are thought to have migrated from southern China into northern Thailand during the 11th century AD. By the 12th century, several independent Thai kingdoms had been established in the north, where they formed a federation known as Lanna Thai. Some had penetrated down into territories theoretically controlled by Mons and Khmers. In 1238, two Thai chieftans joined together, overthrew a local Khmer commander and founded the kingdom of Sukhothai. Though it lasted only a little more than two centuries, Sukhothai was the scene of extraordinary development in art and culture, as well as in politics. Here the Thai alphabet was devised, and the first distinctly Thai forms of architecture and sculpture took shape; moreover, through a system of treaties and alliances, Thai power spread until it was felt over a considerably larger area than the country occupies today.

Ayutthaya, which ruled for four centuries, was a more complex kingdom, one that demonstrated to an even greater degree the Thai gift for assimilation. At its peak, in the 17th century, the capital was larger than London of the same period and as cosmopolitan. Besides the Khmers, Mons, Lao and Burmese with whom the Thais had co-existed for centuries, traders came from India, China, Japan and distant Persia. The first Europeans also arrived, and soon there were Dutch, English, Portuguese, and French "factories," or trading posts, doing business outside the walls of the city.

The remains of Sukhothai and Ayutthaya. Both these ancient capitals were laid out according to ancient Hindu cosmological patterns, with the sacred Mount Mem as the center This was also followed at Angkor Dominating the view of Ayutthaya is Wat Phra Ram, modelled on Khmer architectural style.

A foreigner of the 17th century, depicted in a gold-and-black lacquer painting.

Following the destruction of Ayutthaya by the Burmese in 1767, the capital was moved further south, first to Dhonburi and finally to Bangkok, both on the Chao Phraya River.

When King Rama I of the present Chakri Dynasty decided to relocate his capital from Dhonburi to Bangkok in 1782, one of his goals was to recreate the splendors of Ayutthaya. Outwardly, it was a traditional Thai capital, with traditional values. The king was still known as Chao Jivit, the Lord of Life. He was surrounded by arcane ritual and held absolute power over every aspect of his kingdom, from social matters to national defense.

Yet behind that facade, something new was stirring-or, perhaps more accurately, something as old as Sukhothai. King Ramkhamhaeng, the greatest of the rulers of the first capital, had established the concept of a benevolent, paternalistic monarchy, mindful of the needs of his people and accessible to them. This concept had not always been maintained in Ayutthaya, where rulers became increasingly aloof and even god-like, but early Bangkok saw a return to the ideal, along with deeply-rooted Buddhist beliefs. The king once more became