ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

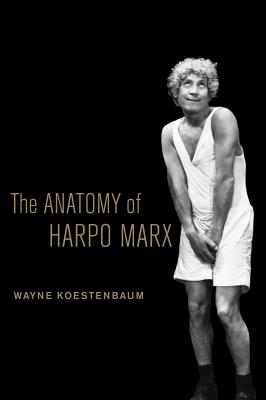

The Anatomy of Harpo Marx. Wayne Koestenbaum

Читать онлайн.Название The Anatomy of Harpo Marx

Год выпуска 0

isbn 9780520951983

Автор произведения Wayne Koestenbaum

Жанр Кинематограф, театр

Издательство Ingram

BIRTH ORDER Harpo is the second brother. (So am I.) Actually, Harpo is the third brother. The very first Marx child, Manfred, died as an infant. (I, too, am the third child: my oldest sibling was stillborn.)

After Manfred came Leonard, a.k.a. Chico, in 1887. Chico is the wheeler-and-dealer, the charming gambler and schemer, the dolt with a stereotypical Italian accent.

In 1888, Adolph was born. He later changed his name to Arthur. We know him, however, as Harpo, the silent one.

In 1890, Minnie Marx gave birth to Julius Henry, who grew into Groucho. Loudmouth with a cigar and painted mustache, he is the most educated of the brothers, and the most celebrated. Deposing Groucho from vocal sovereignty might have been Harpo’s covert aim.

The youngest child, Herbert, born in 1901, ended up as Zeppo, the conventionally handsome, matinee-idol brother, the straight man, the only plausible love-interest.

I’ll ignore the second-to-youngest, Gummo, who doesn’t appear in films.

I have two brothers, one sister. Maybe one day I’ll write about sisters. But my subject here is brothers, or the sensation of losing identity amid fraternal haze.

DUCK-MOUTH Harpo, in his first scene, juts out his lips to compose an indignant chute, like a piggybank slot, or a vacuum-cleaner attachment: I call this mannerism duck-mouth, or chute-mouth. I will often mention it—because it attracts me, and because it confuses me, and because its repetition (again and again the duck-mouth) might have comforted him. He doesn’t want to be a duck, but he seems to realize that duck-mouth brings results. Harpo is a pragmatist, though the fruits of his actions are often ephemeral—trifles like satisfaction, attention, recognition, surfeit, stasis, excess, magnification.

As soon as Chico says, “We sent you a telegram,” Harpo faces forward, greeting the Broadway audience, the camera, or some offscreen presence. Seismic processes—gravity, time, sequence—transpire without intervention; we needn’t manually turn causality’s wheel. Harpo proposes liberation from the need to push reality into prescriptive, fixed formations.

CONSUMING THE INEDIBLE Harpo sits on the couch. Beside him, at attention, gazing upward to the ceiling, and not looking at Harpo, stands a hotel porter in white tux jacket. Harpo removes one of its silver buttons, holds it at a distance to identify its nature, polishes it, and pops it in his mouth. He turns toward the camera, smiles, and nods: tastes good. The experiment succeeded. Eating a button, he violates dietary laws, and ingests the forbidden, the inedible: Judaism calls it “treif.” Harpo plucks another button, chews it, and wipes his mouth with the stooge’s bow-tie. Sacrilege intensifies: loafing on the couch, Harpo rests an ankle in the lackey’s hand. The poor guy, demoted to furniture, ignores the insult and stands stiffly at attention, forced to obey a fool.

Groucho calls Harpo a “groundhog.” Button-eating has turned him into an animal, an escapee from a Kafka story. Becoming an animal (or, as theorists Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari put it, becoming-animal) is a laudable human tendency. Harpo may, in fact, represent a semi-utopian condition of permanent ascent into animality, a variety of exalted consciousness.

All this talk of “exaltation” shouldn’t make you forget that my topic is a dead man. I began writing about Harpo in the months after the death of my favorite singer, the soprano Anna Moffo, who is famous for having a voice of unusual voluptuousness and lightness, and also famous for having lost that voice prematurely. She died on March 10, 2006. The word anatomy, in the title, accidentally refigures her name: Anatomy is “Anna to Me.”

HARPO’S EMPTINESS Emptying myself, I try to become as erased and vigilant as Harpo, who, sitting on the couch while Chico and Groucho talk, maintains a spy’s posture, eyes attuned to ambient frequencies. The porter tries to take Harpo’s suitcase. Harpo, thinking himself robbed, fights back. In the scuffle, the suitcase opens and proves to be empty, like Harpo’s wordless mind. His blankness lacks presuppositions and forbids reciprocation. If you don’t interfere with Harpo, and you satisfy his oral needs (give him coat buttons to chew, and ink to drink), he will be a glad groundhog; but if you thwart him, he will bop you over the head with his honker, a subaltern’s scepter, providing a merely playpen sovereignty.

The title’s “cocoanuts” refers to the Marx Brothers, whose Jewish “nuts,” their testicles, their masculinities, have a suspect, pigmented, tropical undertone; but the fruity title especially applies to Harpo, a sweet nothing with a hollow noggin that promises a forbidden medley of milk and meat.

EXCOMMUNICATION: THE THIRD LETTER Harpo, baby monster, sits on the desk and methodically tears up mail. Excommunication delights him. Advocating witless increase, magnification for magnification’s sake, Harpo is overjoyed to repeat the same action: reach into the mail cubicle, retrieve a letter, rip it up, remove another letter, rip it up. His eyes flash as he probes the postal beehive; his other, unoccupied hand hangs suspended, conducting a phantom orchestra. Enthralling, the speed and efficiency of Harpo’s reverse factory, an assembly line that destroys rather than produces. His gaze pivots between letters and Groucho, to whom the mail-destroying feat is a potlatch obediently offered.

When a hotel employee hands Groucho a telegram (actually, a bill), Harpo intercepts and shreds it. Harpo, bookkeeper, performs his favorite function, erasure, canceling debt in medias res. If asked to perform a three-part task, he skips the middle step. If ordered to deliver a message, he destroys it.

Comedy’s rhythm: do anything, however trivial, three times. Make a motion; repeat it; repeat it again. Harpo’s eyes flash when he tears the third letter. The first two gestures are exploratory. With the third letter, he moves from experiment to ecstasy. Like an anteater examining its prey, or like an absorbed infant contemplating a rattle, Harpo glances at the letter-about-to-be-delivered. By ripping it up, he reenacts the destruction of his own voice. Toward his voicelessness—as toward the letters he aggressively destroys— he exhibits no pity, no chagrin. We might consider language’s disappearance a nightmare, but Harpo finds it Lethean.

RATIOCINATION IS FUNNY Harpo sees what resembles a potato but is actually a sponge; he prongs it with a pen, as if with a fork, and chews experimentally, slowly, quizzically. (We can see him think. For our sake, he exaggerates ratiocination, and turns it into a joke.) With Butoh-precise gestures, he spreads paste on the sponge and drinks the ink from the jar, a mock-teacup. Fussy Harpo examines a bouquet before choosing the ideal blossom to eat, and almost “cracks up” at his own preposterousness.

THE INSTANT OF EYE CONTACT WITH THE VIEWER Note Harpo’s distended, glowing, mesmerized eyes, peering, out their corners, toward the camera. His gaze, no longer shy about confronting us, implies: I know that you see my misbehavior. I like being caught. Harpo recognizes the viewer recognizing him. After bliss, an attack of autohypnosis seizes him and shuts down pleasure; glazed eyes, turning away from the camera, sever our momentary bond.

HARPO