ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

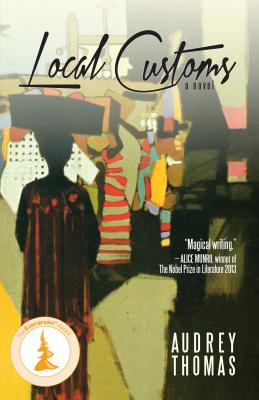

Local Customs. Audrey Thomas

Читать онлайн.Название Local Customs

Год выпуска 0

isbn 9781459708006

Автор произведения Audrey Thomas

Жанр Приключения: прочее

Издательство Ingram

Advance Praise for Local Customs:

“Thomas is at the top of her game with this elegantly written, deeply felt gem of a novel.”

— Ann Ireland, author of

The Blue Guitar and The Instructor

“Once again Audrey Thomas proves that a writer can deliver great narrative even while she is finding new ways to compose a book. I just sat and read her new novel while the world somehow went on without me.”

— George Bowering

Praise for Audrey Thomas’s Writing:

“Thomas has a faultless ear for dialogue, for how people sound.… And she has a camera eye for physical detail.”

— Margaret Atwood

“Audrey Callahan Thomas’s specialty is not a region but a gender. She is intensely, assertively feminine … Mrs. Thomas’s perceptions … are brilliant.”

— New York Times Book Review

“The author’s writing is stylistically brilliant.”

— Publishers Weekly

“Audrey Thomas is not a romantic, nor is she a narrow satirist of false sophistication. She is a realist and a terrible comedian who exposes her characters in a light like ‘the intense glare of the sun against the white walls of the houses.’”

— Globe and Mail

Dedication

To Sarah, Victoria, and Claire

And to the memory of Peggy Appiah

and Monty de Cartier

Carte Generale De L’Afrique by Eustache Herisson, 1829. Dot indicates location of Cape Coast.

Courtesy of the University of Texas Libraries, The University of Texas at Austin.

Epigraph 1

Duncan: “This castle hath a pleasant seat;

the air nimbly and sweetly recommends itself

Unto our gentle senses.”

— Macbeth I, VI, I

“Well,” exclaimed Lord Harvey,

who had appeared to be absorbed in

watching his own shadow on the water,

“I do not think it is such a dreadful

thing to be married. It is a protection,

at all events.”

— Ethel Churchill, by Letitia Landon

“She no sick; she no complain, no nuttin’.

And then she go die, one time.”

— Isaac,

sense-boy at Cape Coast Castle

Epigraph 2

Letty: I can speak freely now that I am dead.

Prologue

MY NAME IS LETITIA ELIZABETH LANDON, nickname Letty, early professional name L., and later L.E.L. It was a shock to several of the young beaux at Oxford when it was revealed that L.E.L., who wrote such sweetly melancholic poetry was a young woman, not a young man. The initials had been my publisher’s idea; they added to the mystery. I was also known, briefly, as Mrs. George Maclean, wife of the Governor of Cape Coast Castle, on the Guinea Coast. (“Mrs. Maclean as was,” as Mrs. Bailey would say. You haven’t met Mrs. Bailey yet, but you will.)

I say “My name is,” not “was,” because your name is your name and stays with you forever; it will still be my name a hundred years from now, two hundred, even if no one by then can remember why it was important. “L.E.L.? Wasn’t there some mystery …”

I was born on 14 August 1802, the eldest of three children, a brother named Whittington and a sister who was an invalid and died young. Our father was a partner in the firm of Adair and Company, who supplied the army during the Napoleonic Wars. He prospered, but then lost most of his money on speculation and the romantic idea of a gentleman’s hobby farm in the country. We became what I suppose one would call “shabby genteel,” a family with a good name who had come down in the world. In spite of being the engine of our rapid descent into almost-poverty, I adored him. It was not his fault that he was impractical, a dreamer, and even less his fault that he died very suddenly of a heart attack. At a very early age I became the financial head of the family and it was lucky for us all that I was not only prolific, but popular.

They said I was a precocious child and knew my letters even before I could string them into words. Once I could actually read, nothing excited me so much as books. I was supposed to have been seen often rolling a hoop with one hand while holding up a book with the other, no doubt some romantic adventure. True or not, it paints a very pretty picture. I do know that I wasn’t the least bit interested in most of the things a young lady should be interested in. I did no embroidery, did not sing or play the piano, never asked for a receipt or a pattern in my life; I was totally deficient in the science of the spoon and the scissors. What I excelled in was words, they flowed from my pen almost as though I had nothing to do with the actual composition; I simply had to be quiet and let them come in. Of course there were revisions — that’s where the hard work comes in, that’s the exhausting part.

I was considered a genius by some, a silly rhymester by others. I think I understood what people wanted, or some people, mostly, but not exclusively, women. I could definitely move about in Society and was welcome at the very best mansions. I was not a debutante, of course. I was never presented at Court in a white dress with the requisite three feathers in my hair, like some gigantic white cockatoo, but I was definitely part of the London literary scene without having to go through the rigors of The Season, or the “Meat Market,” as some wag called it, where the real purpose of all those fifty balls and thirty luncheons and numerous dinners was to secure a suitable husband as soon as possible. If the Honourable Lady Annabelle Thing hadn’t managed to be engaged by the end of her second season, she was considered a failure.

I was invited to select Wednesdays at men’s clubs, where the men attempted to show us how well they could do without us, dining on greenish soup and overdone sole and some sort of pudding remembered from their nursery days; to the National Gallery; to walks in Hyde Park; to house parties in the country where one had to admire everything, from the park to the pigsty and where I never really had the right quantity of clothes for the many changes of wardrobe, but learned how to do wonders with a brilliant shawl and a smile.

I was good at being a guest. I liked talking; I looked charming when I talked. I liked strangers; every stranger presents a new idea. And I knew how to listen, how to make the person speaking to me feel as though he were the most important person in the room. That is a great talent and will take you a long way — even as far as the Gold Coast.

The following is the story of my meeting with George Maclean, our engagement and marriage, our life at Cape Coast Castle, my unexpected death. You will also meet Brodie Cruickshank, another Scot, like George, in charge of the fort at Anamaboe, who became my great friend, and Mr. Thomas Birch Freeman, a Wesleyan missionary, Mrs. Bailey and several other characters of interest.

The story takes place between 1836 and late 1838, in London and at Cape Coast, just before the rains end and the Dry Season is about to begin.

It is curious how much of its romantic character a country owes to strangers, perhaps because they know least about it. I will try, at least, to give some sense of what that world on the coast was like.

It is worthwhile having an adventure, if only for the sake of talking about it afterwards.

“AND WILL THERE BE LIONS AND TIGERS?” I asked.

“If