ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

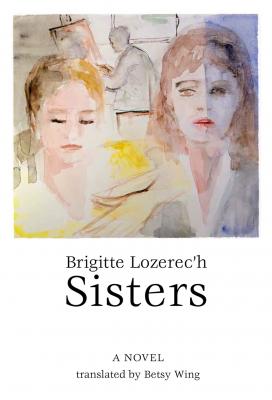

Sisters. Brigitte Lozerec'h

Читать онлайн.Название Sisters

Год выпуска 0

isbn 9781564788313

Автор произведения Brigitte Lozerec'h

Жанр Контркультура

Серия French Literature

Издательство Ingram

We tried to copy them or invent new ones in our notebooks. I rediscovered the pleasure I’d once taken in drawing fruits, birds, rabbits, and flowers to compose a farandole of color and motion. My eyes transformed everything into miniature form, which I set down in multicolored garlands in the margins of my pages. My guilty obsessions showed up here, but you’d have had to know what you were looking for to recognize them. Who could have guessed that the leaves folded across the central vine represented hands under the sheets placed exactly at the intersection of two other stems, there, in the forbidden spot? I alone knew it, and it was wonderful not to be scolded or judged when I showed people my drawings. Nor did anyone know that when I drew a family or rabbits or a nest of birds I never was able to put the young in alongside their parents. Each member of the family had its own leafy branch or teetered on letters that were far away from each other. I was the only one who knew that they were from the same litter or the same hatching and that they were waiting for someone to bring them together again . . .

I never let go of my colored pencils. For my twelfth birthday I asked for brushes and tubes of paint.

My mother took the family as well as Aunt Dilys to the opening of the show at the Willon Gallery on May 13, 1903, scarcely two months after the birth of little François. This was a chance for her to meet Frédéric Thorins and decide whether or not he had any talent in her eyes.

She arrived looking quite haughty, with Eugénie hanging onto her gown and Grandmother, despite having her cane for support on one side, leaning on her arm. M. Versoix, my mother’s second husband, whom I still can’t call anything other than Monsieur, brought up the rear with his son from his first marriage, Alain, a fourteen-year-old boy who meant nothing to me but who had the same little brother as I. We looked at each other with a certain mistrust. We were polite when we spoke, but quite reserved. I would have liked to have William there with us at the opening, but he was preparing for his baccalaureate exams.

The personal history that I had with painting, and that I had now with this artist, whom I’d met a few weeks earlier, was turning into my mother’s business, and I had a strong sense of watching these private connections be taken away from me. Her little group, attentive to her words, followed her from room to room. She analyzed the construction of the works and went into raptures over a particular color, or, whispering to her family what they ought to think, rejected a certain style. Where did she get this knowledge? Was it profound or superficial? I had no memory of having heard her discuss painting when she was at Grandmother’s; rather, all she talked about were things she’d read, or concerts and plays that she went to with our English cousin. Had she gone with my father to art exhibits in London? My memory was completely blank on this point, but I had a question: was it because of this familiarity with art that she had not stood in the way of my taking classes with M. Jacquier? Or had that kindness been, instead, an attempt to make recompense for my abandonment in the convent?

I saw Frédéric Thorins coming toward us in the crowd and had a sinking feeling, as though he represented some wrongdoing in my life and all these people were now going to be exposed to it. Besides, I wanted to protect myself from my family’s judgment concerning the work of a person whom I hardly knew but who belonged to the world that I wanted to enter. A person who knew how to talk about things I felt passionate about. The worst of it was that their point of view might possibly influence me and I was ashamed of this in advance. As soon as he’d greeted me the reflexes instilled in me by my education came to my rescue and provided some guidance. I introduced him to my family, despite how much I regretted having brought these two opposite poles of my existence face to face when they shared no point in common.

How proud I was, however, of my mother’s natural elegance, the gracious yet haughty way she held her head . . . Since her marriage to M. Versoix, she had regained her panache. In another life I’d adored her, and perhaps I still adored her, but in a way that was more reserved, even stifled. She intimidated me, seduced me, crushed me. She still had power over me, while her own mother held all the authority. Which reminded me that I belonged to them. It was at once reassuring and appalling. William, even though he too had been shut away, seemed free to me, by contrast, simply because, being a young man, he was able take the train from Sceaux by himself, get off at the gare du Luxembourg, and hop into an omnibus to come to Grandmother’s, if he didn’t saunter instead along the streets of the Latin Quarter on his way to the home of our mother and her husband on the rue du Four . . . That’s the stuff dreams are made of! Occasionally, without the least concern on his part, he’d even give up his monthly permission to leave school in order to take part in a game of sports or go riding with his fellow students. No one even commented when he decided to do this. The entire family knew he’d begun riding lessons with our father and still was passionate about it. William, less supervised than I, took life head-on.

As I watched my mother at the Willon Gallery, she seemed larger, wiser, and more triumphant in her new existence. Her name was no longer Jeanne Lewly but Jeanne Versoix and I couldn’t get used to it, even though it was almost as though M. Versoix were giving me back the happier woman of before. Still, I couldn’t help but think that now she owed her triumphant air to him, and that it was with him and her new family that she shared it above all. We, the twins, belonged to another life that had led briskly and joyously to bankruptcy, the sale of Swann House, and our return to Grandmother’s.

Feeling the need to build up my self-confidence in the midst of this crowd, I moved toward Frédéric Thorins, who was busy talking with a man. When he caught sight of me, he waved me over and introduced me to the visitor in a manner that I found quite surprising: “Take a good look at her, she’s going to be my next pupil, and I think people will be talking about her some day!” The man, a journalist, turned to look at me, full of curiosity, then he gave Frédéric a knowing wink, which made me very uncomfortable indeed. But at the same time, because the artist himself was watching me so steadily, with eyes that were so warm, so protective, eyes shining with a gleam that was unique, a burst of joy quelled my anxiety. Not only had I just learned that he was thinking of having me for a pupil and that he believed I had a future, he’d also made me conscious of feeling something very pleasant that I was savoring for the first time—something I wouldn’t have known how to encourage. For a brief moment I saw that he thought I was pretty, and I was flattered by that and felt alive.

I had no time to enjoy my happiness. My little sister slipped catlike close beside me, fishing for compliments with a smile and a glance. Her slightly auburn hair, her green eyes, and her voluptuous lips, which were so skilled in the arts of pouting and laughter, formed an adorable mélange that would always be the perfect temptation for portrait painters. In her smocked dress and large collar she was flirtatious and stylish with all the arrogance of her eight and a half years. I’d have liked it better if she had stayed with our little brother.

Eugénie was never able to see any member of the family conversing with someone outside of our circle without forcing her way in. She talked charmingly about herself, about how her music teacher had recognized her gift for the piano, even predicting that because she was so gifted, she might have a career. Eugénie was careful not to mention that this attentive woman had added that one had to work on it every day, if one wanted to be great, which my sister didn’t do. She was always looking for compliments, but, in order to avoid provoking a tantrum by reminding of her obligations, she was left alone to practice her music however and whenever she pleased. A quick glance in my direction made her certain that I wasn’t going to contradict her in front of these gentlemen. I recognized her way of saying “See, me too!” or maybe “Me most!” without actually putting it into words. The two men, charmed with her audacity, smiled and congratulated her on her ambition. We’d interrupted their conversation, so I took the little one by her hand and led her off to our grandmother, who was sitting on a sofa. She’d been keeping an eye on us the whole time.

When our family left the exhibition, Eugénie voiced her challenge: “And what if I painted with you?”

“Would you like that, dear?” my mother replied, giving us an encouraging look.

“Yes,