ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

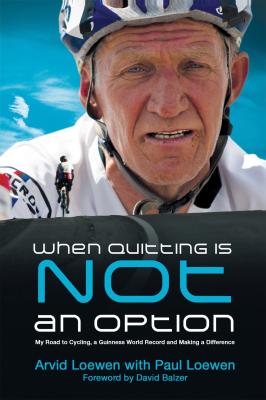

When Quitting Is Not An Option. Arvid Loewen

Читать онлайн.Название When Quitting Is Not An Option

Год выпуска 0

isbn 9781927355497

Автор произведения Arvid Loewen

Жанр Биографии и Мемуары

Издательство Ingram

“Up there.” He flicked his head towards the tree straight in front of us. It was, maybe, 50 feet tall. My little eyes followed the trunk until what my ears heard matched what my eyes saw. A bees’ nest, some 40 feet up in the tree. It was a good 8 inches in diameter and 15 inches long—we had definitely found the sweet jackpot.

“You have a shot?” I asked. He responded by nodding. We didn’t quite speak, didn’t quite whisper. The sound was somewhere between the two, and it blended in with the sounds around us. The last thing we wanted was for our attack on the hive to be spoiled, sending us careening through the trees with nothing to show for it.

“I’ve got a shot,” he said, lifting his arms up into the air. Being older and stronger (for a while, anyway), he always took the shot. With his arms held high in the air, the slingshot cocked and ready to fly, he whispered out of the side of his mouth, not moving his head or letting his eyes leave the target.

“Remember,” he said, “when it comes down, you get it. If they attack, run—but don’t forget the hive.”

Right, I thought. Why am I always the runner? “Okay,” I whispered, sneaking closer to the tree. We were both about 15 feet from its trunk now, the sound of the hive buzzing in waves, rising and falling. He pulled the slingshot tighter, his aim true, and let the first clay bullet fly.

Thwack, it hit the hive. Instantly the buzzing increased in volume. The number of bees outside of the hive increased exponentially. There was a cloud of them now, attacking the tree angrily. Something had disturbed their home, and it was going to pay.

Without taking his eyes off of the hive, Art put another bullet into the slingshot and pulled it back. I held a two-foot club in my hand, spinning it lightly. It was the perfect size and weight, and its role was still to come.

He let loose the second bullet, and it missed the hive by an inch. Standing right beside him, I could trace its flight. The cloud of bees felt that they’d been grazed, and the intensity and volume of the buzzing increased.

Within a few seconds he had let a third bullet fly, and this one found its mark. Another tear appeared in the side of the hive. Like alarm bells had gone off in their home, the rest of the bees swarmed out to inspect what was going on and destroy the intruder. But they had no idea the intruder was far below them.

One more bullet to the hive should have done it—the bees were out of the hive now. The slingshot was the easy part. Art lowered it and hooked it onto his shorts, letting it hang and holding out his hand. I deposited the club into it like a relay baton. He swung it once, twice, testing its weight. Then, with the skill born out of practice, he cocked it back and let it fly. Now that the bees were out of the hive—supposedly—he would knock the hive off the branch, and it would fall to us. Empty of anything other than honey, it would land at our feet. The bees would be stuck upstairs, confused about why their house had just disappeared.

That was the plan, anyway.

His aim was true and the throw was strong—it knocked the hive off the branch. It careened its way towards us—though we still stayed a few feet back—bouncing off of branches until it hit the ground right in front of our feet. It had gaping holes from the bullets, where his shots had torn through it.

I went forward, diligent in doing my job. But something was wrong.

When I picked up the hive, I knew.

The sound of the bees had travelled to us as the hive came down. There were still bees in the hive.

“Run!” Art yelled, and I listened. But I didn’t forget what he’d said earlier—don’t forget the hive. I took off running in Art’s direction. Fear was written all over his eyes as he saw what was in my hand—and what was coming out of it.

Like Olympic sprinters out of the starting blocks we ran—not towards something but away from something. By now the cloud at the top of the tree had realized where their family and friends were and joined in the pursuit.

We hadn’t followed a specific trail, so it was a full-speed tilt through trees and bushes, the branches scraping at us while we dodged the trunks. I bounced off one, then another, clinging tight to the hive—a source of food for a family with little. We came out of the trees and into the open, our bare feet pumping up and down like pistons, our little legs a blur. Behind—and with—us came a horde of bees. Sting after sting after sting after sting. I was trying to swat them, but it didn’t work well with the hive in my hands and bees still pouring out of it.

Art was ahead of me, and we both knew where we were going. A large puddle—deep enough to swim in—was there for the cattle to drink from. Without hesitation we jumped headlong into the water, me still clutching the hive for all it was worth, and held our breath underwater. The bees couldn’t come down, but with the enveloping water and the still beneath the surface came the catch-up of the nerves—and the realization that my body was stinging like it was on fire. There wasn’t a part of me that didn’t feel like the bees were still leeching their poison into me.

I held my breath until I couldn’t anymore, hearing Art thrashing around beside me. I surfaced, only to spit my air out and grab another breath. At the same time I caught a glimpse of the sky around me—dotted with black and yellow bees like stars in the daytime. I didn’t need to be up longer than a second to realize they were still angry. Going back under I held my breath longer, my body fighting against the need to surface.

Several times later—finally—the bees had calmed down enough to leave. I left my head above the surface and waited for Art to come back up. Still stinging from the swarm we’d faced, his face broke into a smile the second he came up.

“You got it?” he asked.

I held up the hive, now soggy but still good, and smiled—13 bee stings were a small price to pay for our sweet loot.

* * *

When my forefathers arrived in Paraguay from Russia, they were given a tent, an ax, a spade, and an ox to share with another family. Given to my grandparents by MCC (Mennonite Central Committee), these tools made life possible, though certainly not simple. It was a meagre beginning, and it set the tone for the years that were to come, including my childhood.

Paraguay was never my family’s destination, fleeing from Russia due to religious persecution. Health concerns made Paraguay the only option available. They would take anybody that could breathe. Dad’s family had aimed for Canada but missed by a few thousand miles. Nevertheless, we were in a country that didn’t care what we worshipped or who we were, and it was now home.

With the tools they were given, my grandparents and their families set to becoming agricultural farmers. This included growing peanuts, cotton, and a small amount of grain. Agricultural farming is very dependent on the weather—particularly rain. The landscape of the Chaco (our territory in Paraguay) is mostly flat, like the prairies, with open fields and meadows. The natural grass (bitter grass that the cattle and horse can’t eat) grows three or four feet high, surrounded by bush. There are very few forests but a significant amount of dense bush. The roads were mud, subject to the dustiness of the dry winter season and the sogginess of the rain. Depending on their condition at the time of travel, they could make getting somewhere very difficult.

In winter the temperature dips colder but rarely below zero Celsius, the main difference being the lack of rain. Dust and sand whip up in columns and clouds, getting into every nook and cranny. The houses aren’t sealed, but the northerly winds would break any seal anyway, scattering the dust and sand in a layer that cakes just about everything. It provides a strange contrast, because the land is often green and yet suffers from significant drought. It’s this drought that has earned the Chaco the nickname “Green Hell,” a gritty yet accurate representation of some of the difficulties of the land.

With the dependency on the weather to co-operate, farming was not simple. Over time most farmers switched over to raising cattle. For my family this was on a very small scale with a small margin of success. The difficulty in growing up in this environment laid the groundwork for my understanding of