ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

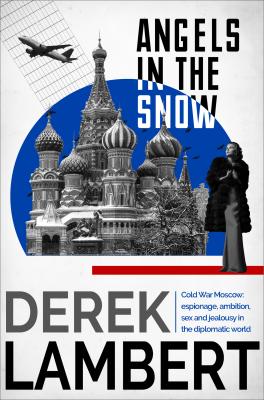

Angels in the Snow. Derek Lambert

Читать онлайн.Название Angels in the Snow

Год выпуска 0

isbn 9780008268312

Автор произведения Derek Lambert

Издательство HarperCollins

‘Perhaps they approve of drunkenness in Britain,’ Keres said.

‘They can hold their liquor—not like you bloody Russians.’

‘And you can hold your liquor, can you?’

Harry belched loudly and painfully. ‘I could drink you under the table,’ he said.

Keres said: ‘I doubt that. See to him, Ivan.’

The bald assistant put down the bread and raw onion he was eating. ‘Strip,’ he said.

‘Balls to you,’ said Harry.

Ivan removed his clothes as easily as if he were undressing a schoolboy. Then he dragged him to the shower, pausing on the way to bite his onion.

‘It’s easier if you don’t resist,’ Keres said. ‘Ivan sometimes loses his temper. Especially if you happen to kick him in the crutch.’

Harry shuddered as the water poured over him. ‘I’ll get you sacked for this,’ he shouted. ‘I’ve got contacts. You see if I haven’t.’ His head was snapped back and the water sluiced over his face and into his mouth.

‘Puny little bastard, isn’t he,’ the first militiaman said. ‘Look at all those scars on his back. Wonder where he got those.’

Ivan put Harry’s clothes in a locker numbered three and threw Harry on to bed number three.

‘Are you going to behave yourself or do we have to strap you down?’ Keres asked.

‘I want to go home,’ Harry said. But he lay quietly on the bed, shivering violently, thin and sharp and beaten. They threw a soiled blanket over him.

On one side of him a jovial drunk who had been ordered not to sing aloud hummed ballads to himself. He was a regular client and was allowed to keep his guitar under his bed. He was a Georgian with curly black hair and a moustache; he looked like a bandit who would enjoy carousing or killing with equal appetite.

On the other side an alcoholic twitched in dribbling sleep. He awoke intermittently and whimpered with fear, knees drawn up to his stomach, palsied hands protecting his face. His mouth was stained with tobacco tar and his face was as starved as a jockey’s.

Harry brooded on the ignominy of it. He with the biggest stomach and bladder capacity in the beer hall carted off to a sobering-up station. When he closed his eyes the darkness heaved around him. He dozed and heard the call of ships in the Pool of London and went hop-picking as a child with his mother. He was awoken by Nosov’s voice in the adjoining room.

The cold encountered between the entrance to the chapel and the station had not improved the appearance of Nosov’s nose which was mauve and polished.

‘They’ll have to move us out soon,’ he told Keres. ‘You can’t run our business in a monastery. We’ll become the laughing stock of Moscow. I just tripped over a cross lying outside. Left there deliberately I shouldn’t wonder. How can we be expected to make a contribution to the celebrations of the anniversary of the glorious Revolution in a monastery?’

Keres shrugged. ‘I think you’re making too much of it,’ he said. ‘It’s only being restored as a museum after all.’

Nosov moved Ivan’s bread and onion from his desk. ‘That’s even better,’ he said. ‘A sobering-up station in a museum. That will really get us a good reputation. People wandering in and thinking we’re part of the museum. We’ll have to put our drunks in glass cases. No, we’ve got to get new premises. We cannot allow ourselves to be humiliated any longer.’

‘I think you are too sensitive,’ Keres said.

Nosov thumbed through the papers on his desk. ‘How many have we got in now?’

‘Four. One more was brought in while you were resting. He isn’t causing any trouble.’

‘Four. There was a time when all the beds would have been occupied and we’d have had a couple on the floor besides.’

‘When the winter sets in we’ll be full again. They’ll have their old excuse—drinking to keep the cold out.’

Nosov wandered into the next room. Harry, who had decided that he was completely sober, sat up and said: ‘I demand to be sent home.’

Nosov appeared startled. He shook his head. ‘This is all I need,’ he said. And added: ‘Keres, please leave the room.’

Five minutes later Harry Waterman was dressed. Keres looked at him in amazement. ‘Where do you think you’re going?’ he asked.

‘I’m going home,’ Harry said.

Nosov said: ‘This man is discharging himself.’

‘But he can’t,’ Keres said. ‘It’s against the regulations. And what about the fine?’

‘I’ll pay the fine,’ Harry said. ‘If that’s all that’s bothering you.’ He turned to Nosov. ‘And now may I go home?’

Nosov pointed to the door. ‘Clear out,’ he said. ‘There are plenty of taxis outside.’

The blue mosaic eyes of Christ watched icily as Harry picked his way past snow-felted heaps of crosses and eroded sculptures.

‘Why did you let him go?’ Keres demanded.

Nosov sighed. ‘Comrade,’ he said, ‘may I ask a favour?’

‘There’s no harm in asking.’

‘We’ve been good friends. Good colleagues devoted to the cause. Doing our small bit for the furtherance of the aims of the State. May I plead with you never to mention this to anyone again?’

‘But why did you let him go?’

‘He happens to be married to my daughter,’ Nosov said. ‘This very night my wife is sleeping at his flat.’ He tugged at his nose as if he were trying to remove it.

‘What a disgrace,’ said Harry’s mother-in-law. ‘What a terrible disgrace.’

‘It can’t be all that bloody disgraceful,’ Harry said. ‘After all it’s your husband’s work.’

‘To think that my daughter’s husband should be taken to a sobering-up station.’

‘Your husband’s sobering-up station.’

‘Good kind man that he is,’ said Nosov’s wife who frequently told her husband that he was the most evil and cruel man in the Soviet Union. ‘Letting you go like that.’

Harry’s wife Marsha said: ‘I was worried about you, Harry. I thought perhaps you’d been hurt in a fight. You do provoke people so.’

‘I don’t get hurt,’ Harry said. ‘It’s the others who get hurt. And as for your husband …’ he rounded on his mother-in-law ‘… the only reason he let me go was because he knew he’d be the laughing stock sobering up his own son-in-law. That and the fact that he was scared stiff of what you’d say.’

‘I would have been all for keeping you in,’ she said. ‘Best place for you if you ask me.’

‘No one is asking you. But the point is Leonid thought you would be angry if he kept me in and brought disgrace to the family. As it is I was never officially there. And the drunks won’t be able to spread gossip about me when they wake up in the morning.’

His mother-in-law was planted in front of the dead television set to which she seemed to address her remarks. She was eating small biscuits as hard as nuts from a box on the table beside her. She was grossly fat, Harry thought. Like most Russian women. A sexless lump of peasant stock.

‘What’s for dinner?’ Harry asked.

‘Strogonoff,’ said his wife. ‘I’m sorry, Harry,