ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

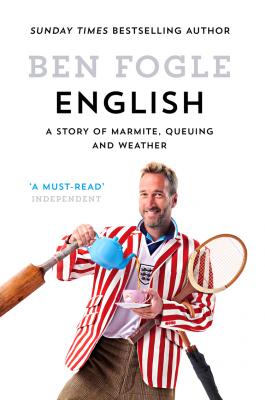

English: A Story of Marmite, Queuing and Weather. Ben Fogle

Читать онлайн.Название English: A Story of Marmite, Queuing and Weather

Год выпуска 0

isbn 9780008222260

Автор произведения Ben Fogle

Жанр Юмор: прочее

Издательство HarperCollins

Arguably our earliest pioneer was Captain James Cook. He was born in 1728 in a small village near Middlesbrough, the son of a farm worker. One of the few naval captains to rise through the ranks, Cook’s achievements are pretty impressive. Between 1763 and 1767 he was responsible for charting the complex coastline of Newfoundland aboard HMS Grenville. On an expedition commissioned by the Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, he commanded HMS Endeavour to witness the transit of Venus across the sun – a rare event visible only in the southern hemisphere – sailing to Tahiti via Cape Horn. Once the astronomer, Charles Green, had made his observations they sailed on to New Zealand and then became the first Europeans to navigate the length of Australia’s east coast. Cook claimed the region for Britain and named it New South Wales.

In 1772, a year after his return home, Cook set out on a second voyage to look for the southern continent. They nearly succeeded but had to return before discovering it because of the extreme cold. For his final voyage, he set out to discover the fabled North-West Passage, which the world’s navigators and cartographers presumed was the link between the Atlantic and the Pacific Ocean. He was unsuccessful and ended up landing on Hawaii, where he was stabbed by an islander and died on 14 February 1779. Despite a lifetime of success, his untimely death seems to me to mark the beginning of the era of heroic failures.

While Cook circumnavigated the globe, nearly a century later a new generation of explorers would begin a new land grab for some of the last unexplored corners of the planet, the polar regions.

I took on my own ocean in 2005 when I teamed up with the double Olympic gold rowing champion James Cracknell to row the Atlantic. Ocean-rowing is a peculiarly English occupation that has escalated in popularity over the last decade. Goodness knows why. Rowing a tiny 21ft boat made of plywood and stuck together with glue nearly 3,500 miles across the Atlantic has to count as the most miserable seven weeks of my life.

What makes it so English? Well, the slowness and monotony have an appeal a little like that of cricket; the challenge itself is both eccentric and utterly pointless; and it is far from glamorous or sexy. In many ways, ocean-rowing epitomizes so many English traits. There’s a certain ‘because-it’s-there’ feeling to the whole enterprise.

So why did I choose to do it? Well, I think my Englishness played a part.

Growing up, I relished the stories of those great earlier explorers and pioneers. A particular favourite was Captain Robert Falcon Scott, who was born in 1868 in Plymouth, Devon. He led two expeditions to the Antarctic. On the Discovery expedition in 1901–4 he broke a new southern record by reaching latitude 82°S and discovered the Polar Plateau. Then in 1910 he set off for the Terra Nova Expedition, which was to end infamously in tragedy. He reached the South Pole on 17 January 1912 a month after Roald Amundsen’s Norwegian expedition. They perished on the return journey having missed a meeting point with the dog teams. Temperatures suddenly dropped to -40°C as they trudged northwards.

In a farewell letter to Sir Edgar Speyer, treasurer of the fund raised to finance the expedition, and dated 16 March 1912, Scott wondered whether he had missed the meeting point and fought the growing suspicion that he had in fact been abandoned by the dog teams: ‘We very nearly came through, and it’s a pity to have missed it, but lately I have felt that we have overshot our mark. No-one is to blame and I hope no attempt will be made to suggest that we had lacked support.’

On the same day, one of his companions, Laurence Oates, who had become frostbitten and who had gangrene, voluntarily left the tent and walked to his death. Scott wrote down Oates’s last words, some of the most famous ever recorded: ‘I am just going outside and may be some time.’ If ever there was an English way of dying, surely that was it?

I was always taken by the tragic tale of Captain Scott, so perhaps it is no surprise that when I finally got a chance to take part in a race to the South Pole, once again James Cracknell and I teamed up for an escapade which I recounted in The Accidental Adventurer. In a gratifyingly English outcome, we were pipped to the finish by the Norwegian team, by the tiny margin of four hours. Heroic failures to the last.

Born around the same time as Scott was another plucky Englishman, George Herbert Leigh Mallory. He took part in three British expeditions to Mount Everest in the early 1920s. First was the 1921 reconnaissance expedition, which reached 22,500 feet (6,900m) on the North Col. In the second, a year later, the team including Mallory got to 27,320 feet (8,320m) but could not summit. But it was his 1924 summit attempt with climbing partner Andrew ‘Sandy’ Irvine that is most deeply shrouded in mystery. Both men disappeared as they attempted to become the first to stand on top of the world. They were last seen about 245 vertical metres from the summit. The fate of the climbers remained a mystery until 1 May 1999, when a research expedition sponsored by the BBC to find the climbers’ bodies came across Mallory’s corpse at 26,755 feet (8,155m). Irvine’s body remains somewhere up there. Did they reach the top? The subject remains one of intense speculation and continuing research. Whatever the answer, Mallory and Irvine only added to the public’s enduring love of the heroic failure.

When you’re going into the unknown, it’s quite possible that you’ll disappear and, if you’re English, the odds are that bit shorter. Perhaps one of the greatest explorer mysteries is that of Lieutenant Colonel Percival ‘Percy’ Harrison Fawcett, born in 1867 in Torquay, Devon.

His upbringing was about as English as you could get. He was educated at Newton Abbot Proprietary College; in 1886, he joined the Royal Artillery and was stationed in Ceylon (as it then was). He studied mapmaking and surveying and joined the Royal Geographical Society. Military life bored him and after a spell working undercover for the British Secret Service in North Africa, he received a commission from the RGS to use his surveying skills to settle a border dispute between Bolivia and Brazil. He arrived in La Paz in June 1907, aged thirty-nine. Fantastic stories started to trickle back to London. He claimed to have shot a giant 62ft anaconda, as well as many other animals unknown to zoologists – including a ‘cat-like’ dog and a giant poisonous Apazauca spider. He made seven expeditions through the jungle and his adventures became the inspiration for Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Lost World. After volunteering to serve in the First World War he returned to South America with his eldest son, Jack, in 1925. Before the war, he’d heard local legends about a lost city called ‘Z’, somewhere in the Brazilian jungle. It became an obsession. He was convinced the city existed in the Mato Grosso region and he, his son and Jack’s best friend, the heroically named Raleigh Rimell, plunged into the jungle. They were never seen again. Percy left instructions with his wife that, if they should disappear, no one should come after them; but ever since hundreds of expeditions have taken place with the sole purpose of locating this true English heroic failure.

It continues to surprise me the astonishing rate at which we have generated great adventurers compared to the size of our nation. Take a look at the current generation of great English explorers: Colonel John Blashford-Snell, Sir Ranulph Fiennes, Sir Chris Bonington, Sir Robin Knox-Johnston and Dame Ellen MacArthur, to name just a few. We are celebrated for our explorers, but I think somehow we tend to celebrate those who have a go and fail spectacularly rather than those who easily come out on top.

A. A. Gill wrote in his book The Angry Island: Hunting the English:

For the English, real character is built not by winners, but by losers. Anyone can be a good winner … It is in losing that the individual really discovers what they’re made of, and it was in coming a good second that the kernel of the truth in the lesson of sport lay, because winning a game of muddied oafs or flannelled fools is transiently unimportant, but being able to cope with failure and disappointment, to turn around the headlong impetus of adrenalin, effort, expectation and hope, and still shake hands with your opponent and pick up the bat or the boot the next day – that’s the proving and honing and the toughening of character.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу