ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

Иностранные языки

Различные книги в жанре Иностранные языки, доступные для чтения и скачиванияАннотация

Marc Chagall was born into a strict Jewish family for whom the ban on representations of the human figure had the weight of dogma. A failure in the entrance examination for the Stieglitz School did not stop Chagall from later joining that famous school founded by the Imperial Society for the Encouragement of the Arts and directed by Nicholas Roerich. Chagall moved to Paris in 1910. The city was his “second Vitebsk”. At first, isolated in the little room on the Impasse du Maine at La Ruche, Chagall soon found numerous compatriots also attracted by the prestige of Paris: Lipchitz, Zadkine, Archipenko and Soutine, all of whom were to maintain the “smell” of his native land. From his very arrival Chagall wanted to “discover everything”. And to his dazzled eyes painting did indeed reveal itself. Even the most attentive and partial observer is at times unable to distinguish the “Parisian”, Chagall from the “Vitebskian”. The artist was not full of contradictions, nor was he a split personality, but he always remained different; he looked around and within himself and at the surrounding world, and he used his present thoughts and recollections. He had an utterly poetical mode of thought that enabled him to pursue such a complex course. Chagall was endowed with a sort of stylistic immunity: he enriched himself without destroying anything of his own inner structure. Admiring the works of others he studied them ingenuously, ridding himself of his youthful awkwardness, yet never losing his authenticity for a moment.

At times Chagall seemed to look at the world through magic crystal – overloaded with artistic experimentation – of the Ecole de Paris. In such cases he would embark on a subtle and serious play with the various discoveries of the turn of the century and turned his prophetic gaze like that of a biblical youth, to look at himself ironically and thoughtfully in the mirror. Naturally, it totally and uneclectically reflected the painterly discoveries of Cézanne, the delicate inspiration of Modigliani, and the complex surface rhythms recalling the experiments of the early Cubists (See-Portrait at the Easel, 1914). Despite the analyses which nowadays illuminate the painter’s Judaeo-Russian sources, inherited or borrowed but always sublime, and his formal relationships, there is always some share of mystery in Chagall’s art. The mystery perhaps lies in the very nature of his art, in which he uses his experiences and memories. Painting truly is life, and perhaps life is painting.

Аннотация

Egon Schiele’s work is so distinctive that it resists categorisation. Admitted to the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts at just sixteen, he was an extraordinarily precocious artist, whose consummate skill in the manipulation of line, above all, lent a taut expressivity to all his work. Profoundly convinced of his own significance as an artist, Schiele achieved more in his abruptly curtailed youth than many other artists achieved in a full lifetime. His roots were in the Jugendstil of the Viennese Secession movement. Like a whole generation, he came under the overwhelming influence of Vienna’s most charismatic and celebrated artist, Gustav Klimt. In turn, Klimt recognised Schiele’s outstanding talent and supported the young artist, who within just a couple of years, was already breaking away from his mentor’s decorative sensuality. Beginning with an intense period of creativity around 1910, Schiele embarked on an unflinching exposé of the human form – not the least his own – so penetrating that it is clear he was examining an anatomy more psychological, spiritual and emotional than physical. He painted many townscapes, landscapes, formal portraits and allegorical subjects, but it was his extremely candid works on paper, which are sometimes overtly erotic, together with his penchant for using under-age models that made Schiele vulnerable to censorious morality. In 1912, he was imprisoned on suspicion of a series of offences including kidnapping, rape and public immorality. The most serious charges (all but that of public immorality) were dropped, but Schiele spent around three despairing weeks in prison. Expressionist circles in Germany gave a lukewarm reception to Schiele’s work. His compatriot, Kokoschka, fared much better there. While he admired the Munich artists of Der Blaue Reiter, for example, they rebuffed him. Later, during the First World War, his work became better known and in 1916 he was featured in an issue of the left-wing, Berlin-based Expressionist magazine Die Aktion. Schiele was an acquired taste. From an early stage he was regarded as a genius. This won him the support of a small group of long-suffering collectors and admirers but, nonetheless, for several years of his life his finances were precarious. He was often in debt and sometimes he was forced to use cheap materials, painting on brown wrapping paper or cardboard instead of artists’ paper or canvas. It was only in 1918 that he enjoyed his first substantial public success in Vienna. Tragically, a short time later, he and his wife Edith were struck down by the massive influenza epidemic of 1918 that had just killed Klimt and millions of other victims, and they died within days of one another. Schiele was just twenty-eight years old.

Аннотация

During the Renaissance, Italian painters would traditionally depict the wives of their patrons as Madonnas, often rendering them more beautiful than they actually were. Over centuries in religious paintings, the Madonna has been presented as the clement and protective mother of God. However, with the passing of time, Mary gradually lost some of her spiritual characteristics and became more mortal and accessible to human sentiments. Virgin Portraits illuminates this evolution and contains impressive works by Michelangelo, Caravaggio, Rubens, Fouquet, Dalí, and Kahlo.

Аннотация

Mega Square Sculpture spans over 23,000 years and over 120 examples of the most beautiful sculptures in the world: from prehistoric art and Egyptian statues to the works of Michelangelo, Henry Moore and Niki de Saint-Phalle. It illuminates the wide variety of materials used and the evolution of styles over centuries, as well as the peculiarities of the most important sculptors.

Аннотация

They met in 1928, Frida Kahlo was then 21 years old and Diego Rivera was twice her age. He was already an international reference, she only aspired to become one.

An intense artistic creation, along with pain and suffering, was generated by this tormented union, in particular for Frida. Constantly in the shadow of her husband, bearing his unfaithfulness and her jealousy, Frida exorcised the pain on canvas, and won progressively the public’s interest. On both continents, America and Europe, these commited artists proclaimed their freedom and left behind them the traces of their exceptional talent.

In this book, Gerry Souter brings together both biographies and underlines with passion the link which existed between the two greatest Mexican artists of the twentieth century.

Аннотация

Pierre-Auguste Renoir was born in Limoges on 25 February 1841. In 1854, the boy’s parents took him from school and found a place for him in the Lévy brothers’ workshop, where he was to learn to paint porcelain. Renoir’s younger brother Edmond had this to say this about the move: “From what he drew in charcoal on the walls, they concluded that he had the ability for an artist’s profession. That was how our parents came to put him to learn the trade of porcelain painter.” One of the Lévys’ workers, Emile Laporte, painted in oils in his spare time. He suggested Renoir makes use of his canvases and paints. This offer resulted in the appearance of the first painting by the future impressionist. In 1862 Renoir passed the examinations and entered the Ecole des Beaux-Arts and, simultaneously, one of the independent studios, where instruction was given by Charles Gleyre, a professor at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts. The second, perhaps even the first, great event of this period in Renoir’s life was his meeting, in Gleyre’s studio, with those who were to become his best friends for the rest of his days and who shared his ideas about art. Much later, when he was already a mature artist, Renoir had the opportunity to see works by Rembrandt in Holland, Velázquez, Goya and El Greco in Spain, and Raphael in Italy. However, Renoir lived and breathed ideas of a new kind of art. He always found his inspirations in the Louvre. “For me, in the Gleyre era, the Louvre was Delacroix,” he confessed to Jean. For Renoir, the First Impressionist Exhibition was the moment his vision of art and the artist was affirmed. This period in Renoir’s life was marked by one further significant event. In 1873 he moved to Montmartre, to the house at 35 Rue Saint-Georges, where he lived until 1884. Renoir remained loyal to Montmartre for the rest of his life. Here he found his “plein-air” subjects, his models and even his family. It was in the 1870s that Renoir acquired the friends who would stay with him for the remainder of his days. One of them was the art-dealer Paul Durand-Ruel, who began to buy his paintings in 1872. In summer, Renoir continued to paint a great deal outdoors together with Monet. He would travel out to Argenteuil, where Monet rented a house for his family. Edouard Manet sometimes worked with them too. In 1877, at the Third Impressionist Exhibition, Renoir presented a panorama of over twenty paintings. They included landscapes created in Paris, on the Seine, outside the city and in Claude Monet’s garden; studies of women’s heads and bouquets of flowers; portraits of Sisley, the actress Jeanne Samary, the writer Alphonse Daudet and the politician Spuller; and also The Swing and The Ball at the Moulin de la Galette. Finally, in the 1880s Renoir hit a “winning streak”. He was commissioned by rich financiers, the owner of the Grands Magasins du Louvre and Senator Goujon. His paintings were exhibited in London and Brussels, as well as at the Seventh International Exhibition held at Georges Petit’s in Paris in 1886. In a letter to Durand-Ruel, then in New York, Renoir wrote: “The Petit exhibition has opened and is not doing badly, so they say. After all, it’s so hard to judge about yourself. I think I have managed to take a step forward towards public respect. A small step, but even that is something.”

Аннотация

Flowers are the centerpiece in the majority of pictorial still-lifes. By painting their colours and forms, artists from Brueghel to O’Keeffe have created symbols for both life and mortality. Van Gogh’s sunflowers, Monet’s water lilies and Matisse’s bouquets are, of course, unforgotten. Most of the works contained in Flowers are true masterpieces, which have often marked whole epochs and styles.

Аннотация

Sargent was born in Florence, in 1856, the son of cultivated parents. When Sargent entered the school of Carolus-Duran he attained much more than the average pupils. His father was a retired Massachusetts gentleman, having practised medicine in Philadelphia. Sargent’s home life was penetrated with refinement, and outside it were the beautiful influences of Florence, combining the charms of sky and hills with the wonders of art in the galleries and the opportunities of an intellectual and artistic society. Accordingly, when Sargent arrived in Paris, he was not only a skilful draughtsman and painter as a result of his study of the Italian masters, but he also had a refined and cultivated taste, which perhaps had an even greater influence upon his career. Later in Spain, it was chiefly upon the lessons learned from Velázquez that he found his own brilliant method.

Sargent belongs to America, but is claimed by others as a citizen of the world, or a cosmopolitan. Sargent, with the exception of a few months at distant intervals, spent his life abroad. The artistic influences which affected him were those of Europe. Yet his Americanism may be detected in his extraordinary facility to absorb impressions, in the individuality he evolved, and in the subtlety and reserve of his methods – qualities that are characteristic of the best American art.

Аннотация

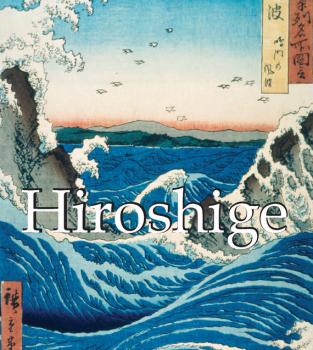

The art of the Ukiyo-e reflected the artistic expression of an isolated civilisation which, when it became accessible to the West, significantly influenced a number of European artists. The three masters of Ukiyo-e, Hokusai, Utamaro and Hiroshige, are united here for the first time to create a true reference on Japanese art. The three masters rank highly among the most famous Japanese artistic productions of all time. This new title of the Prestige of Art collection will be a reference for art students and Japanese art lovers.

Аннотация

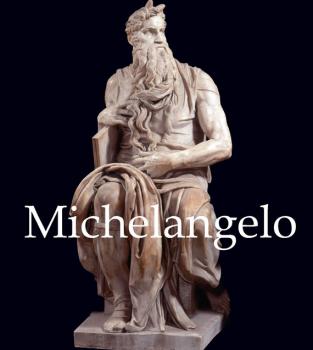

Michelangelo, like Leonardo, was a man of many talents; sculptor, architect, painter and poet, he made the apotheosis of muscular movement, which to him was the physical manifestation of passion. He moulded his draughtsmanship, bent it, twisted it, and stretched it to the extreme limits of possibility. There are not any landscapes in Michelangelo's painting. All the emotions, all the passions, all the thoughts of humanity were personified in his eyes in the naked bodies of men and women. He rarely conceived his human forms in attitudes of immobility or repose. Michelangelo became a painter so that he could express in a more malleable material what his titanesque soul felt, what his sculptor's imagination saw, but what sculpture refused him. Thus this admirable sculptor became the creator, at the Vatican, of the most lyrical and epic decoration ever seen: the Sistine Chapel. The profusion of his invention is spread over this vast area of over 900 square metres. There are 343 principal figures of prodigious variety of expression, many of colossal size, and in addition a great number of subsidiary ones introduced for decorative effect. The creator of this vast scheme was only thirty-four when he began his work. Michelangelo compels us to enlarge our conception of what is beautiful. To the Greeks it was physical perfection; but Michelangelo cared little for physical beauty, except in a few instances, such as his painting of Adam on the Sistine ceiling, and his sculptures of the Pietà. Though a master of anatomy and of the laws of composition, he dared to disregard both if it were necessary to express his concept: to exaggerate the muscles of his figures, and even put them in positions the human body could not naturally assume. In his later painting, The Last Judgment on the end wall of the Sistine, he poured out his soul like a torrent. Michelangelo was the first to make the human form express a variety of emotions. In his hands emotion became an instrument upon which he played, extracting themes and harmonies of infinite variety. His figures carry our imagination far beyond the personal meaning of the names attached to them.