ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

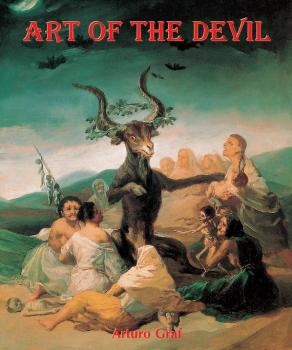

Arturo Graf

Список книг автора Arturo GrafАннотация

“The Devil holds the strings which move us!” (Charles Baudelaire, The Flowers of Evil, 1857.)

Satan, Beelzebub, Lucifer… the Devil has many names and faces, all of which have always served artists as a source of inspiration. Often commissioned by religious leaders as images of fear or veneration, depending on the society, representations of the underworld served to instruct believers and lead them along the path of righteousness. For other artists, such as Hieronymus Bosch, they provided a means of denouncing the moral decrepitude of one’s contemporaries.

In the same way, literature dealing with the Devil has long offered inspiration to artists wishing to exorcise evil through images, especially the works of Dante and Goethe. In the 19th century, romanticism, attracted by the mysterious and expressive potential of the theme, continued to glorify the malevolent. Auguste Rodin’s The Gates of Hell, the monumental, tormented work of a lifetime, perfectly illustrates this passion for evil, but also reveals the reason for this fascination. Indeed, what could be more captivating for a man than to test his mastery by evoking the beauty of the ugly and the diabolic?

Аннотация

„Der Teufel hält die Fäden, die uns bewegen!“ (Charles Baudelaire, Die Blumen des Bösen, 1857.) Satan, Beelzebub, Luzifer… der Teufel hat viele Namen und Gesichter; sie alle haben Künstlern stets als Inspirationsquelle gedient. Bilder von Teufeln wurden oftmals von kirchlichen Personen von hohem Rang in Auftrag gegeben, um, je nach Gesellschaft, mit Bildern der Furcht oder Ehrfurcht und mit Darstellungen der Hölle die Gläubigen zu bekehren und sie auf den von ihnen propagierten rechten Pfad der Tugend zu geleiten. Für andere Künstler, wie z. B. Hieronymus Bosch, waren sie ein Mittel, um den völligen moralischen Verfall seiner Zeit anzuprangern. Auf dieselbe Weise hat die Beschäftigung mit dem Teufel in der Literatur oftmals Künstler inspiriert, die den Teufel mithilfe von Bildern austreiben wollten; dazu gehören insbesondere die Werke von Dante Allighieri und Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. Im 19. Jahrhundert fühlte sich die Romantik zunächst von dem mysteriösen und ausdrucksvollen Gehalt des Themas angezogen und setzte die Verherrlichung der Böswilligkeit fort. Auguste Rodins Höllentor, ein monumentales Lebenswerk, für das er sich sehr gequält hat, stellt nicht nur diese Leidenschaft für das Böse perfekt dar, sondern enthüllt auch den Grund für diese Faszination. Was könnte in der Tat fesselnder, motivierender für einen Mann sein, als seine künstlerische Meisterschaft zu prüfen, in dem er die Schönheit im Hässlichen und Diabolisch darstellt?

Информация о книге

Автор произведения Arturo Graf

Жанр Изобразительное искусство, фотография

Серия Temporis

Аннотация

« C’est le Diable qui tient les fils qui nous remuent ! » (Charles Beaudelaire, Les Fleurs du Mal, 1857) Satan, Belzébuth, Lucifer… Le Diable possède de multiples noms et visages qui, toujours, furent une grande source d’inspiration pour les artistes. Longtemps commanditées par les instances religieuses, pour en faire, selon les civilisations, un objet de crainte ou de vénération, les representations du monde des ténèbres eurent souvent vocation à instruire les croyants et à les guider dans le droit chemin. Pour d’autres artistes, tel Hieronymus Bosch, elles étaient un moyen de dénoncer la dégradation des moeurs de leurs contemporains. Parallèlement, au fil des siècles, la littérature offrit une nouvelle inspiration aux artistes qui souhaitaient exorciser le mal par sa représentation imagée, notamment au travers les oeuvres de Dante ou de Goethe. À partir du XIXe siècle, la période romantique, attirée par le potentiel mystérieux et expressif suggéré par un tel sujet, exalta, elle aussi, cet attrait pour le maléfique. La Porte de l’Enfer d’Auguste Rodin, oeuvre d’une vie, monumentale et tourmentée, est la parfaite illustration de cette passion pour le Mal et nous permet également d’entrevoir la raison de cette fascination. Car en effet, quoi de plus envoûtant pour un homme que d’user de son meilleur savoir-faire pour représenter la beauté de la laideur et du diabolique ?

Информация о книге

Автор произведения Arturo Graf

Жанр Изобразительное искусство, фотография

Серия Temporis

Аннотация

“The Devil holds the strings which move us!” (Charles Baudelaire, The Flowers of Evil, 1857.) Satan, Beelzebub, Lucifer… the Devil has many names and faces, all of which have always served artists as a source of inspiration. Often commissioned by religious leaders as images of fear or veneration, depending on the society, representations of the underworld served to instruct believers and lead them along the path of righteousness. For other artists, such as Hieronymus Bosch, they provided a means of denouncing the moral decrepitude of one’s contemporaries. In the same way, literature dealing with the Devil has long offered inspiration to artists wishing to exorcise evil through images, especially the works of Dante and Goethe. In the 19th century, romanticism, attracted by the mysterious and expressive potential of the theme, continued to glorify the malevolent. Auguste Rodin’s The Gates of Hell, the monumental, tormented work of a lifetime, perfectly illustrates this passion for evil, but also reveals the reason for this fascination. Indeed, what could be more captivating for a man than to test his mastery by evoking the beauty of the ugly and the diabolic?

Информация о книге

Автор произведения Arturo Graf

Жанр Изобразительное искусство, фотография

Серия Temporis