ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

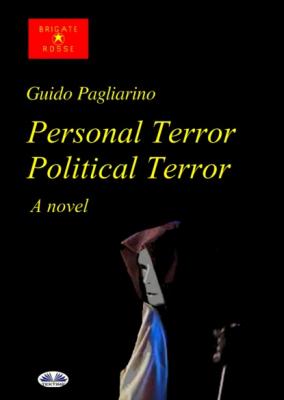

Personal Terror Political Terror. Guido Pagliarino

Читать онлайн.Название Personal Terror Political Terror

Год выпуска 0

isbn 9788835426301

Автор произведения Guido Pagliarino

Издательство Tektime S.r.l.s.

Unfortunately, unlike my friend, I was not and am not a believer; I say unfortunately because, being no longer a young man, I think more often of death and its putrefaction than I did in the past and, if is there is only nothing after our last breath, the tragic futility of life. In any case, it had been precisely this pessimistic feeling that, from a young age, led me to that same desire for justice that drove my friend, even if for me it was a justice that could only be earthly. Convinced as I was that in the cosmic tragedy in which I had a part, complete solidarity between humans was at least indispensable according to the ethos I considered timeless, which every person honors, I had the highest disdain for those who consciously curtailed the gift of life of others, already so brief, and towards violent people in general who caused anguish to human beings during the few years on earth which they were granted.

And I completely agreed with Vittorio when he said that, since the ‘60s of the XX century, civility had been brutalized little by little as many of the traditional philosophical-social or religious ideals weakened and were finally lost. Thus the life of those very people had become simply putting their own selfishness into practice, according to what my friend called the rule of I do as please if it’s seems convenient for me.

Vittorio had made rapid advances in his career from the early 1970s, and had been promoted to Deputy Commissioner at an early age. Then, unfairly, nothing further. He had automatically moved to a higher level only on the day he retired with the pension of Commissioner, as regulations required.

My friend had neither family nor next of kin: he had been a widower with no children for a long time. I was a bachelor who was equally alone, and we felt like brothers.

I’m Ranieri Velli - they call me Ran - journalist and writer and, in the 50s and 60s of the last century, I was a colleague with the rank of deputy sergeant of the then Commissioner Vittorio D'Aiazzo in the Public Security Guards Corp.

I was the younger of the two, just sailing along, let’s say, towards sixty-eight, with a birthday the following 1st of August 2001. Like Vittorio I was already receiving a pension, although I had not ceased my activity as a columnist in the daily press. In the distant past, when there were still no faculties of Communication Sciences and even a non-graduate could become a journalist after the usual internship, I had worked at the glorious Gazzetta del Popolo, a Turin newspaper that, after stops and starts in its last decade of life, had ceased publication altogether on December 31, 1983. So I had moved on to another newspaper, La Gazzetta Libera, founded the following year. It had nothing to do with the previous homophonic daily, even though it too had been created as counterpoint in Turin to the immortal La Stampa which, in essence, meant FIAT. Thanks to the subsidies of an economic group that had an interest in it, the new Gazzetta, even though it never reached the same circulation numbers of the previous one, was still viable at the start of the twenty-first century.

Though Vittorio was my only friend, he instead had more than one, even it they were not as close. Evaristo Sordi could also call himself one of Vittorio’s friends despite not having frequented him socially. Years before, he had been his side-kick in the Homicide Section of the Squadra Mobile after I, his predecessor and part-time writer, had tendered my resignation to devote myself entirely to writing. Evaristo had arrived at the highest career level for a non-graduate and was a senior inspector of sUPS (sostituto Ufficiale di Pubblica Sicurezza, meaning deputy Public Security Officer), commonly called "deputy commissioner" and performing those duties. Not much younger than I, and not far off retirement, the man sported an impressive grey mustache for a long time and despite his age still had a lot of hair, which was salt-and-pepper too. He was a robust figure, just like my friend Vittorio who, unlike Evaristo, was not a very tall man. I was the tallest of the three by quite a bit, almost six feet two, and I had always been very thin although, unfortunately, in recent years I had become a little hunched because of my bad habit, common in tall people, of bending down to the many interlocutors of lesser stature, starting with Vittorio himself.

Vittorio had learned of the first crime from the evening news on television and the following morning had read about it calmly in our newspaper, in an article by the chief crime editor Carla Garibaldi, an unmarried colleague in her forties. She was a woman about five feet eight tall and because of the excessive amount of body building which she "carried out daily" as she had told me, had arms and calves, and probably thighs, a little too muscular for my tastes of an old fashioned kind of man. A protruding jaw and a nose which was too small for the shape of her considerably broad face made her quite ugly. On the other hand, she was a person of great culture with a frank and self-effacing character, and I got along well with her, unlike certain entitled brats on our newspaper.

Just as for cases in the past, by way of me, there had been an exchange of information between Vittorio and Carla, and vice versa which all things considered was to her advantage because my friend was usually in possession of first-hand information, given that he often visited Sordi at Police Headquarters. He had already had crucial clues from the retired commissioner in previous cases, so it was not only out of respectful friendliness that she often welcomed Vittorio into her office and, at times, to the crime scenes themselves and listen to his opinions. In the case of the Ear Monster too, she had very willingly kept Vittorio close.

My friend sometimes went to visit another of his former employees, Deputy Commissioner Giandomenico Pumpo who, after a period as Chief Commissioner leading a special department that dealt with magic, esoteric, pseudo-religious and satanic groups, the ACT, Anti Sect Team, sat in the very place that had once been D'Aiazzo’s. Although not as close a friend as Sordi, Pumpo also allowed the old policeman to extract some news out of him now and then which was useful for his parallel investigations.

The second crime took place five days after Mrs Capuò Tron had been murdered, in October at that point. The victim was Giovanna Peritti Verdani, a 60-year-old widow and pensioner who lived alone in an apartment on Corso Agnelli inherited from her husband. She had a daughter but she was married and lived in Asti. She infact had discovered the body, shortly after 10:00pm of the same day of the murder.

It was her custom to phone her mother every evening, but had not had an answer that time, even though the phone had rung many, many times from 7:30pm onwards; and shortly after 9:00pm the daughter, very worried knowing that her mother never went out after dark, had jumped in the car and had come to Turin. Arriving about an hour later in front of her mother's building and after buzzing uselessly on the intercom, she had let herself in with the spare key she had with her, had gone upstairs and opened her mother’s apartment, which was closed with only a half turn of the lock, as she would later tell the police.

After turning on the light, she had made the gruesome discovery of her mother lying dead on the floor in the entry hall, with her mouth gaping in a grimace of pain, her eyes wide open, blood and brain matter spilling from one ear and a large hematoma on her head.

It would be established that the bruising had been caused by a heavy domestic vase being dropped onto the head, and on which the anatomo-pathologist would find traces of the victim's scalp. The doctor would also determine that, in all certainty, death was due to an ice pick pushed into the ear until it pierced the brain.

The dead woman’s daughter, who barely had time to drop onto a chair, had fainted. When she came to her senses around 10:10pm as she had ascertained on her wristwatch, she had managed to call 113 even though she was still in shock.

Around 11:00pm I had phoned Vittorio on