ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

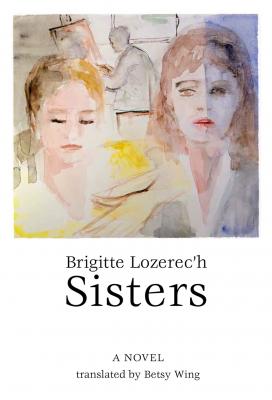

Sisters. Brigitte Lozerec'h

Читать онлайн.Название Sisters

Год выпуска 0

isbn 9781564788313

Автор произведения Brigitte Lozerec'h

Жанр Контркультура

Серия French Literature

Издательство Ingram

“Well, child, Madame Chesneau can’t go with you!” Grandmother fired back, giving the impression that I should know it wasn’t the moment to ask her anything at all, no matter what.

Young girls don’t go out on the streets alone—that was something I’d known as long as I could remember. What would happen if I disobeyed? Would attackers suddenly leap out from porches and alleys or from the entrance to the metro to menace me? After six years in a convent and two years under the surveillance of a grandmother and her lady companion, I lacked all instinct for the outside world and knew nothing about the habits of what I took to be society at large. Flanked by my family when I was out walking, I deeply wanted to feel something of the real city, something of the intense excitement that never touched me because I was so thoroughly insulated. My world consisted of what I could see of the few people, the workers and servants of whom I knew only their public face, and then the few things I thought I knew of a life that was more refined, revealed to me entirely through how certain people dressed and carried themselves; I could sense subtle differences in their behavior and was curious to know more, but everything outside apparently threatened some invisible danger. What was I being protected from? That’s what I hoped to find out, if with a slight rush of apprehension.

Which brings us again to that day which began with a strange disturbance in the house, when something told me that I might take advantage of my grandmother’s panic.

“I’ll just run out and come right back, Grandmother! I promise I’ll hurry.”

She’d known for a long time that if I didn’t draw or paint every day I became impatient and aggressive, thanks to all manner of anxieties even I wasn’t quite aware of. So, with a wave of her hand, as if to brush away some flies, she murmured as she went down the hall, “Don’t take forever—I trust you! Just this one time, Mathilde!”

I raced down the staircase as fast as I could go, my coat still half-buttoned and my gloves in my hand, without even taking time to put my hat on straight—either driven by the fear that she might change her mind, or perhaps in my haste to know who I was once I was alone in the midst of strangers on the boulevards. On my way down rue Blanche the idea came to me of going to immerse myself in the lively crowds at the gare Saint-Lazare, where I’d feel life swarming around me. I laughed, lighthearted and alone, looking at the stores and cafes as if they might have changed overnight, weaving my way through the onlookers, the peddlers, the horse carriages, the junkman at the crossroads. On the other side of the road, on one of the buildings that I thought I knew very well, I was amazed to discover caryatids standing on either end of a porch and holding up a broad stone balcony. “I’ll have to come back some day and sketch them in pencil,” I thought. Just as I was about to set out to cross the congested street, I hesitated . . . If I didn’t muster my courage all these strangers would see the slight anxiety unsettling my euphoria. I might have been unaware of where the danger lay, but these strangers all knew for certain. The women all seemed happy to me and the men good-natured in spite of the overcast skies of early March. Free in their midst I’d have liked to run the way I did as a child, until I was almost out of breath and dizzy, in the lane along Marble Hill Park, where our house was next to last before a bit of meadow began, hidden by a hedge. The Thames flowed down below.

On the steps to the station, a crowd of travelers was going up and down, a rhythmic stream of people. Suddenly an invisible hand pulled me back to my childhood, to the time I’d just been thinking about. An arrow stuck in my heart made me stop short, there on the Cour de Rome. I was looking at the stone arcades, the clock, the station’s large windows, all with a fascination that was becoming more and more painful. We’d just arrived in Paris, right here, in the spring of 1895—my twin brother, William, was holding my hand, and our little sister, Eugénie, still an infant, was asleep in the arms of our mother who was dressed in mourning. It seemed to me that it was at the bottom of these stairs that happiness got away from us forever—though we didn’t know it at the time. William and I weren’t quite nine years old, and now, at almost seventeen, I saw that nothing had changed about this station or this crowd. The only thing different was that now, ever since the turn of the century, a few automobiles were mixing in among the horse carriages.

Yet how long ago that all seemed! I was there at the foot of the stone steps both in the past and in the present. As if I were arriving there to greet us. I remembered that my brother and I had been beside ourselves with the joy of our adventure when we left London. After crossing the gray swells stirred up by a north wind, then an interminable train ride, we’d arrived at this very spot. Fatigue, perhaps, had added to the excitement we felt as the children we were then, in this noisy, crowded Cour de Rome—simultaneously huge and too small. Our father, buried two months earlier in Twickenham, wasn’t really dead for us yet. We were still expecting to see him emerge from the crowd, with his arms open for us to leap into them so he could hug us and murmur “my lovely twins.” The feeling of his absence had not yet eaten into our souls, attacked our memories, gnawed away at our existence.

Dazed, I’d have stood there indefinitely, enduring the pain of standing at the frontier separating me from a lost happiness, at the foot of the steps leading to the gare Saint-Lazare. This boundary felt so real, I could almost touch it. I’d have liked to cross over it, go back in time the way I did in my incoherent dreams, and catch hold of the harmonious years spent in our home with its pretty name: Swann House, our beloved place at the end of Montpelier Row in Twickenham. All those names still sing inside me like the notes of a nursery song that might once have rocked me to sleep.

Intimidated and traipsing along behind our mother, we were approached by two women, one of them more refined looking than the other, who were waiting for us in the throng. The more I stared at them, the more I heard them ask us about our crossing, the more I knew that I knew them, but when and where had I seen them before? Which one was my grandmother? The driver, with the help of a porter, tied our baggage down on a carriage, while the horse tossed his head and pawed the ground, making me feel very sorry for him. How unhappy he must be so far from fields and forests! As for myself, lost in this crowd, all of them speaking French, laughing in French, I was sure I was the only one paying any attention to the creature. His loneliness and submission broke my heart. I hadn’t yet said hello to the two women lingering over my little sister with worried looks on their faces.

I’d willingly embraced one of the two women after she’d said “Hello, dear child,” but five months later, at the end of August, she was the one who, with her daughter, my mother, would exile me to the Sacré-Coeur convent.

Though I’d come out now with the notion of melting into the bustling city, with no thought of digging up old memories, it became obvious that it was here on the steps of the gare Saint-Lazare that our little unit had come undone, and not at the English cemetery where our father, Frank Lewly, lay at rest.

I now know that stones have memories. I looked at that façade as if I could decipher all the layered palimpsests, inscribed there ever since men and women began to arrive here to experience moments of life that were full of despondence or hope, the throes of love or abandonment as the trains went on coming and going . . . That day I discovered that streets have memories too, as do monuments and bridges.

Leaving the Cour de Rome I was unaware that I was on my way to a meeting arranged by fate on the pont de l’Europe—a meeting that was to determine the course of the rest of my life. I set out for it at a brisk pace.

I was brought back to the present by the cold gripping my feet and legs. I knew that the moment of freedom