ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

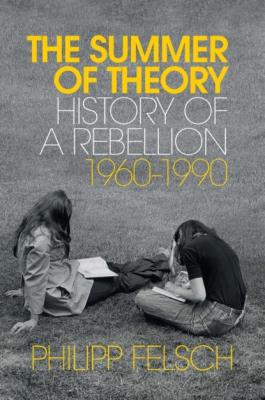

The Summer of Theory. Philipp Felsch

Читать онлайн.Название The Summer of Theory

Год выпуска 0

isbn 9781509539871

Автор произведения Philipp Felsch

Жанр Социология

Издательство John Wiley & Sons Limited

And, while catching up on Adorno’s past publications, Gente also had to keep up with his current production. What with the author’s growing popularity and presence in the West German media, that was a time-consuming task. Together with a handful of like-minded readers – who were thought nuts by their fellow students – Gente formed an ‘information syndicate’ to lay hands on everything Adorno published, no matter how obscure the outlet. ‘He’d just written something in Neues Forum, so I ran to Schöller’s and bought it.’45 (Marga Schöller’s historic shop in Knesebeckstrasse was where West Berlin’s revolutionary students bought their literature before the little Red bookshops usurped the market.) The thick dossier Gente compiled as an Adorno fan would later become his seed capital as a publisher. His theory archives grew more diverse with each passing year, and eventually spawned the first Merve titles.

Among the earliest articles Gente clipped and filed is a commentary by Adorno on the 1959 Frankfurt Book Fair. In it, Adorno expressed a vague ‘anxiety’ that had oppressed him for some time at the sight of each season’s new publications: it seemed to him that the books no longer looked like books. The covers had become ‘advertising’, degrading the reader to a consumer as they made their advances. They heralded the ‘liquidation of the book’ in ‘all too intense and conspicuous colours’. A proficient stylist, Adorno needed no more than two columns to run the gamut of his cultural criticism: the diagnosis of death where life only appeared to persist; the successive moments of horror, realization and despair. For Adorno would not be Adorno if he did not finish with a dialectical sidestep and declare the industrialization of the book market inevitable. The melancholy over the deterioration of a cultural artefact ‘in which truth presents itself’ was all the deeper for that.46

Every new medium has kindled in its turn the apocalyptic discourse of the death of the book – television, in particular, and later the screen culture of the digital age.47 In the post-war period, that discourse was first heard as a critique of the paperback book. In the same year in which Adorno reported on the Frankfurt Book Fair, the Hessian radio network broadcast Hans Magnus Enzensberger’s ‘analysis of paperback production’, an examination of the leading German publishers’ catalogues. Rowohlt’s rororo series, named for the mass-producing rotary printing press, had entered the German market as early as 1946. From then on, paperback production had only grown, in all segments of the industry. In his critique, an attempt to grasp the significance of the paperback phenomenon, Enzensberger essentially came to the same conclusions as Adorno. He, too, saw intellectual culture deteriorating to a commodity, the reader demoted to a consumer. Of course, the fear that cheap paperbacks would be not so much read as briefly leafed through and then stuffed back onto the shelf, or even thrown away, was not limited to Germany. It was a common motif of cultural criticism wherever publishers pressed forward into the new book market – in Paris and Rome no less than in Frankfurt. The paperback seemed to be a harbinger of the global ‘mass culture’.48 What worried Enzensberger most was the reader’s disenfranchisement: he thought the flood of new titles robbed readers of their ability to judge. In the ‘literary supermarket’, where anticipated sales took the place of the cultural canon, helpless readers were prey to the manipulations of the culture industry.49

Neither Enzensberger nor Adorno could have imagined in 1959 that they would owe their own success as authors to the generation of paperback readers.50 Once Minima Moralia appeared in a soft cover in the early 1960s, no one carried it around in hardcover any more. Adorno later attained high sales figures in the various paperback series published by Suhrkamp. The new medium, which, from its critics’ perspective, ensured the conformance of the consumer, was supplying difficult ideas – initially as contraband – to a growing readership.51 The history of theory is not conceivable without these upheavals in the book market, and that is what makes Peter Gente, the book collector and book producer, such an exemplary figure in that history. It was the Penguin designer Hans Schmoller, a German-Jewish emigrant, who remarked in 1974 on the paradox of the ‘paperback revolution’: ‘though in the West paperbacks have become big business, this has not prevented their publishers from giving free rein to expressing ideas strongly opposed to established political and economic systems and indeed advocating their overthrow’.52

Adorno Answers

After having been forgotten for an interim, Adorno was omnipresent in the 1960s.53 He filled the lecture halls and appeared in the young mass media – most of all, radio, the German ‘counter-university’ of the post-war period.54 The barely modulated voice, separating its words with tiny pauses, was unmistakable. It was a hit with the audiences of the cultural programmes and the night-time airwaves. Learning by radio how to read Hegel: such breathtakingly highbrow content sends today’s cultural editors into raptures of nostalgia. It is hardly imaginable any more, Joachim Kaiser wrote for Adorno’s hundredth birthday, what influence the philosopher had in those days.55 At that time, when Kaiser himself fell under that influence, he described it in these terms: ‘Anyone writing, speculating, politicizing, aestheticizing today must engage with Adorno.’56 No one has held a comparable monopoly since. In the seventies, as Marxism grew sclerotic, Critical Theory submerged in the think-tank on Lake Starnberg – the Max Planck Institute for the Study of the Scientific-Technical World, whose second director was Jürgen Habermas – and the French came to dominate the theoretical airspace, another German generation grew accustomed to living in the philosophical provinces, dependent on onerously decrypted imports from a Mecca of theory across the Rhine. The Weltgeist didn’t live here any more.

Before ’68, when German society had maintained an eloquent silence about its recent past, it had been otherwise – this was one of history’s ironies. Dangerous ideas hadn’t had to be smuggled across the border then; they were right there in Frankfurt. And if you weren’t one of the chosen few who personally inhabited Adorno’s orbit, as Joachim Kaiser did, you could pick up the Frankfurt phone book, look up his address and write to him.57 Adorno’s philosophical presence seems in retrospect almost to have demanded direct communication. The Situationists in Munich apparently thought so too, although their missive also contains a first grain of resistance against Adorno. In 1964, five years after they had taken on Max Bense, they posted on German university buildings their famous ‘lonely hearts advert’, composed of excerpts from the as yet largely unknown Dialectic of Enlightenment, in block letters: ‘THE CULTURE INDUSTRY HAS SUCCEEDED SO UNIFORMLY IN TRANSFORMING SUBJECTS INTO SOCIAL FUNCTIONS THAT, TOTALLY AFFECTED, NO LONGER AWARE OF ANY CONFLICT, THEY ENJOY THEIR OWN DEHUMANIZATION AS HUMAN HAPPINESS, AS THE HAPPINESS OF WARMTH’, and more in that vein. Readers who felt the poster made them stop and think were invited to contact ‘Th. W. Adorno, Kettenhofweg 123, 6 Frankfurt/Main’. Among those who wrote to the address given was the University of Stuttgart, which sent an invoice for the cost of removing the posters, although Adorno, like Bense before him, had known nothing of the Situationists’ action.58

The ‘nexus of deception’ that Adorno depicts in sombre colours penetrated to the capillaries of day-to-day life. In the absence of functional differentiation, which had no place in his theory, nothing was safe from the falseness of society as a whole – and from that fact Adorno derived an almost boundless authority. The numerous unsolicited letters among his archived papers show how willing his German readers and listeners were to appeal to his expertise. His remark in Minima Moralia that, in a society in which ‘every mouse-hole has been plugged, mere advice exactly equals condemnation’ did not stop them from asking the book’s author for advice in almost every imaginable circumstance.59 He gave it, sometimes hesitantly, sometimes reluctantly, but he always made an honest effort to help. ‘Intellectual people’, Adorno wrote in one of his return letters, must have had a great need for spiritual guidance at that time.60

The questions, arriving from every state of the Federal Republic and from all social classes, make up an intellectual portrait of post-war West Germany. Doctoral candidates in philosophy sent Adorno their dissertation projects; disillusioned students turned to him in search of meaning. The expectations people had in writing to Adorno are