ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

The Summer of Theory. Philipp Felsch

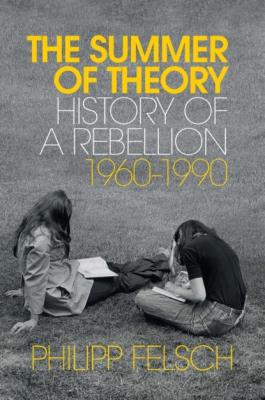

Читать онлайн.Название The Summer of Theory

Год выпуска 0

isbn 9781509539871

Автор произведения Philipp Felsch

Жанр Социология

Издательство John Wiley & Sons Limited

Merve has been called the ‘Reclam of postmodernism’ – Reclam, of course, are the publishers of the ‘Universal Library’, the yellow, pocket-sized standard texts that no German student can do without. Merve was the German home of postmodernism, and practically owned the copyright to the German word for ‘discourse’.6 Merve had made a name for itself in the 1980s, primarily with translations of the French post-structuralists. Its cheaply glued paperbacks were a guarantee of advanced ideas, and the pop-art look of their un-academic styling was ahead of its time. The coloured rhombus on the cover of the Internationaler Merve Diskurs series was a well-established logo whose renown rivalled that of the rainbow rows of Suhrkamp paperbacks.

I remember well the first Merve titles I read. It wasn’t easy, in Bologna in the mid-1990s, to get them by mail order. My intention had been to spend a semester there studying with Umberto Eco, but Eco’s lectures turned out to be a tourist attraction. Whatever the famous semiotician was saying into his microphone at the far end of the lecture hall was easier to assimilate by reading one of his introductory books. In retrospect, that was a stroke of luck, because it forced me to look for an alternative. And the search for a more intense educational experience led me – twelve years after his death – to Michel Foucault. My Foucault wasn’t bald and didn’t wear turtlenecks, and although he occasionally spoke French, his Italian accent was unmistakable. But his grand rhetorical flourishes and his tendency to overarticulate his words are engraved in my memory. In his best moments, he came very close to the original. Valerio Marchetti had heard the original Foucault at the Collège de France in the early 1980s, if I remember correctly, and absorbed – as I was later able to verify on YouTube – his way of talking as well as his way of thinking. He was a professor of early modern history at the University of Bologna. His lecture course, which was attended by very few students, was devoted to a topic only a Foucauldian could have come up with: ‘Hermaphroditism in France in the Baroque Period’. I was spellbound on learning of the seventeenth-century debates in which theologians and physicians had argued about the significance of anomalous sex characteristics.7 I had never heard of such a thing at my German university, where philosophy students read Plato and Kant. I hung on Marchetti’s every word, attending even the Yiddish course that he taught for some reason, and started reading the literature he cited: Michel Foucault, Paul Veyne, Claude Lévi-Strauss, Georges Devereux … I waited weeks for the German translations to arrive in the post. I read more than I have ever read since, and collected excerpts on coloured file cards. In the heat of the Italian summer, the ‘microphysics of power’ and the ‘iceberg of history’ stuck to my forearms.8

In 2008, I hadn’t touched these books in years. Their spines crumbled with a dry crackle when I opened them. Inside I discovered vigorous pencil marks, reminding me what a revelation theory had been to me in those days. But at a decade’s remove, that experience seemed strangely foreign: it seemed to belong to an intellectual era that was now irretrievably past. I went to Karlsruhe to have a look at the materials that Peter Gente had turned over to the Centre for Art and Media Technology. In the forty heavy boxes that had not yet been opened – much less catalogued – perhaps I would find a chapter of my own Bildungsroman. They contained the publisher’s correspondence with the famous – and the less famous – Merve authors, along with the paper detritus that lined the road to over 300 published titles: newspaper clippings, notes, budgets, dossiers … While Gente rested, I supposed, in the shade of coconut palms, I immersed myself in his papers. Only gradually did I realize that what I was looking at were not the typical assets of a liquidated business: it was the record of an epic adventure of reading.

The oldest documents dated back to the late 1950s, when Gente discovered the books of Adorno. That discovery changed everything. For five years, the young man ran around West Berlin with Minima Moralia in his hand, before he finally got in touch with the author. By then, Gente was in the middle of the New Left’s theoretical discussions, combing libraries and archives in search of the buried truth of the labour movement. He was everywhere, cheering Herbert Marcuse in the great hall of Freie Universität, demonstrating with Andreas Baader in Kurfürstendamm, running into Daniel Cohn-Bendit in Paris a few weeks before May of ’68. Later, he had discussions with Toni Negri, sat in jail with Foucault, put up Paul Virilio in his shared flat in Berlin. There was never any question that he belonged to the movement’s avant-garde – yet he kept himself in the background. It was a long time before he found his role; he didn’t care to play the part of an activist, nor that of an author. ‘Tried to intervene, but wasn’t able to do so’ was his summary of the year 1968.9

From the beginning, Gente had been, above all, a reader. The scholar Helmut Lethen, who had known him since the mid-1960s, called him the ‘encyclopaedist of rebellion’.10 He knew every ramification of the debates of the interwar period; he knew how to lay hands on even the most obscure periodicals; his comrades’ key readings were selected on his recommendation. Compared with Baader – whom he supplied with books in Stammheim Prison – Gente embodied the opposite end of the movement: the man I met in 2010, and questioned about his past, interacted with the world through text.11 In preparation for our conversations, he would arrange books, letters and newspaper articles, and he picked them up in turn as he talked, to underscore one point or another. In the echo chamber of the theories that he mastered as no other, he had found his vital element. Professor Jacob Taubes, a gifted reader in his own right who counted Gente among his disciples, attested in 1974 to Gente’s talent for ‘dealing intensively with unwieldy texts’.12 One of the peculiarities of the theory-obsessed ’68 generation is that hardly any theoreticians originated in their ranks. ‘As they silenced their fathers, they allowed their grandfathers to be heard again – preferably those who had been exiled’,13 the cultural journalist Henning Ritter wrote. Was he thinking of Peter Gente, who had served alongside him as a student assistant to Taubes in the 1960s? From that perspective, Gente was the ideal New Leftist: a partisan of the class struggle mining the archives.14

Gente travelled to Paris and brought back texts by Roland Barthes and Lucien Goldmann, authors no one knew in Berlin. Towards the end of the sixties, when the leftist book market began booming, he picked up odd editorial jobs. But he didn’t find his life’s theme until, in his mid-thirties, he decided to start his own business: in 1970, he and some friends and comrades founded the publishing company Merve Verlag. Initially, they called themselves a socialist collective. As their political beliefs evolved, however, the organization of their work changed as well. For two decades, Merve shaped the theory scene of West Berlin and West Germany. From the student movement’s latecomers to the avant-garde of the art world, everyone got their share of dangerous thinking: Italian Marxism, French post-structuralism, a dash of Carl Schmitt, topped off with Luhmann’s sober systems theory.

2 Heidi Paris and Peter Gente, West Berlin, around 1980.

But Merve probably never would have been anything more than just a minuscule leftist publisher whose products occasionally turn up in Red second-hand bookshops if Gente hadn’t met Heidi Paris. In the masculine world of theory, where women were all too often reduced to the roles of mothers or muses, she was a pioneer.15 She led the group’s publishing policy in new directions, contributing to the dissolution of the collective. From 1975 on, she was Gente’s partner both in work and in a personal relationship. The couple composed Merve’s legendary long-sellers, established authors such as Deleuze and Baudrillard in Germany, and steered their publishing house into the art world, where it has its habitat today. They produced books that didn’t want to be read at university; they transformed