ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

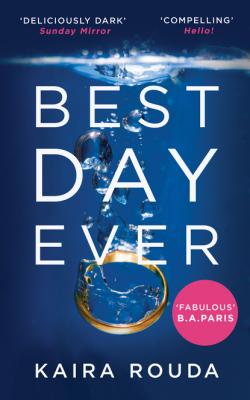

Best Day Ever. Kaira Rouda Sturdivant

Читать онлайн.Название Best Day Ever

Год выпуска 0

isbn 9781474064682

Автор произведения Kaira Rouda Sturdivant

Жанр Морские приключения

Серия MIRA

Издательство HarperCollins

Mia shifts in her seat, angling her body toward me as much as possible for someone strapped in by her seat belt, and asks, “Do you really think the strawberries will take hold? I mean, they looked like they were from the photos Buck sent me. They might even have grown a little. But things can change.” I notice she holds her phone in her hands now; her lovely fingers, accented by a cheery red—strawberry red—fingernail polish, move quickly across the small keypad. She was a copywriter at the advertising agency when I met her, and she has amazing keyboard speed still.

“It says strawberry plants should be bought from a reputable nursery. I’m just not sure I picked the right one. And they need deep holes, wide enough to accommodate the entire root system without bending the roots. Very persnickety plants,” she continues. Her lips are pursed together, as if she has eaten a sour berry.

“I’m sure they’re fine,” I reassure her. “No one will nurture them more than you.” A black sports car passes us on our right, only a flash of metal actually, because it’s moving so quickly. I hadn’t even seen it coming in my rearview mirror. It’s funny how things can sneak up on you, appear out of nowhere.

“It’s like having babies again, or puppies,” she says, ignoring the race car as I turn on my blinker and slide us out of the passing lane. “Don’t plant too deep, it says. The roots should be covered, but the crown should be right at soil surface. I should call Buck and ask him to check on the crowns.”

She glances at me, no doubt catching my smirk. First, what kind of name is B-U-C-K? I mean, really. But despite his ridiculous name, Buck Overford is a nice enough guy, I guess. He’s our neighbor at the lake, a widower even though he’s about my age, who likes to talk gardening with my wife. I should be clear. I’m forty-five, and Mia is only thirty-three. Buck is closer to my age than hers, maybe even a bit older. I look younger anyway. Not that we’re old geezers by any stretch. Buck does have this affinity for gardening, which to me is a woman’s thing, so that makes him older, weaker than me in my book.

At least gardening is what Mia tells me she and Buck have been talking about since we met him last summer. It was just after our moving truck had left. He brought over a bottle of Merlot, a nice one if memory serves, and the three of us spent a pleasant evening together on the screened porch until it was time for us to find our boys and get them ready for bed. The boys were free-range chickens up at the lake, had been every summer we’d rented. Now that we were owners, members, they’d increased their span of wandering, it seemed.

There were countless wholesome activities at the lake to draw their attention, from sailing lessons to shuffleboard, skateboarding to bike riding. Sometimes, we’d find them sitting by the edge of the water, skipping rocks, like they’d stepped out of a Norman Rockwell painting. It was all perfectly safe, these endless summertime activities that delighted our boys and made them beg us to head to Lakeside whenever possible. When it was bedtime, though, finding them, corralling them and then getting them into bed was a process best left for family only. We never wanted witnesses to that exhausting exercise.

“Right, I don’t need to bother Buck. I can check the crowns as soon as we get there,” Mia says in my direction before returning her attention to her phone screen.

“Good call.” I check the rearview mirror for any more speeding sports cars. I had an expensive sports car before, of course. I’ll likely have one again one day when my lifestyle dictates a change, I muse, taking in the interior of my sensible Ford Flex. Room for the whole family, and as many strawberry plants as Mia could handle planting. I can haul as much of the boys’ sports equipment as they can throw my way. It is a sensible, practical car. For a responsible family man. It fits me perfectly, this car. Me and my hot, newly skinny again wife. If she loses any more weight, though, she’ll disappear. It’s a real shame about the nausea she’s been struggling with. The latest doctor is convinced it’s stress-related. He told her to meditate.

“Did you know my strawberry plants’ runners are called ‘daughter’ plants?” she asks. The air between us pulses, I feel it. Ping.

“No, I didn’t,” I say, taking a deep breath before I realize I am doing it. It’s funny how the absence of a daughter catches your breath at the strangest times, over the silliest topics. “No ‘son’ plants? How sexist.”

“I still wish we’d tried,” Mia says quietly, stirring the age-old pot. Just that topic, that old leathery shoe of a stew makes me swallow something bitter. I cough, trying to clear my throat, my dark mind.

“Can we not have that old discussion today, of all days?” I ask. I focus on the farmland beginning to open up on either side of the road. We’re finally out of the reaches of the city, finally free from the responsibility, the shiny office buildings, bespoke suits and country clubs that that part of civilization values. I would miss golf if I had to live in the country, of course. And many other things. Country visits are for weekends, a touch-base with our more rural and simple selves. Not a place to live full-time. I hope we aren’t going to disagree this early in our country excursion.

Mia turns to me and I can hear her gentle, agreeable smile in her next words. “Of course, no fighting. This is our happy day, the start of a wonderful weekend. I just didn’t realize until this moment about strawberry seedlings and ‘daughter’ plants. I should have grown peppers.” Her voice is soft, a stealth dagger to my heart. This statement, the peppers, is a jab. Sure, we could have tried to get pregnant one more time, but I was convinced it would be another boy. We had two of those, perfect little specimens, each a miniature version of me, as they should be. I realize Mia would enjoy seeing a little version of herself walking around this world, following in her footsteps. But why tempt fate?

I glance at my wife. Did I see Mia wipe under her eye? No, I’m sure it must be an errant eyelash. This topic is almost as old as Sam, our youngest, who is six. We have been arguing, disagreeing let’s call it, over our phantom daughter—her name would have been Lilly, Mia had said over and over again—for six years. The whole thing is absurd. She should be counting her blessings, like her strawberry daughters at her beautiful lake house, for example. She should be thankful for everything she has, everything I’ve provided, not missing something, someone who never existed. I feel myself squeeze the steering wheel, watch my knuckles whiten.

“Or beans. Green beans. Those would be fun to grow,” I say in a concerted effort to play along. I have a passion for green beans and have since I was a child. I’ve learned not to question why. It’s just a fact, like the impossibly blue May sky or the brown-green fields stretched out for miles on either side of the car.

I remember when I was a kid and my parents took us to a fancy restaurant in town—this was long before their tragic accident, of course. Before everything changed. Just goes to show you, one thing can happen and poof, all bets are off.

People said it was an odd twist of fate, bad luck that both of my parents had decided to take a nap in the afternoon. Mom’s friends in the neighborhood told the police my mom hardly ever rested during the day. But she had Alzheimer’s, early stage, so things changed all the time. Bottom line was she did take a nap that day. My dad was slowing down in his old age even though he was stubborn and wouldn’t admit it. He napped daily. While my mom’s disease was progressing, she still functioned, still had more energy than he had. Sure, she forgot little things like her neighbor’s name, but until then she hadn’t forgotten big ones—like turning off the car when she had parked it in the garage, most notably.

But my dad always napped, from twelve thirty to two every afternoon. He’d pull out his hearing aids, put the golf channel on the television and commence his obnoxiously loud snoring. He sounded like an uncontrolled train screeching down the tracks. I can almost picture my mom returning from her errand, pulling the car into the garage and pushing the button to close the garage door. She’d walk inside the house, accidentally leaving the door connecting the garage to the house open, the