ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

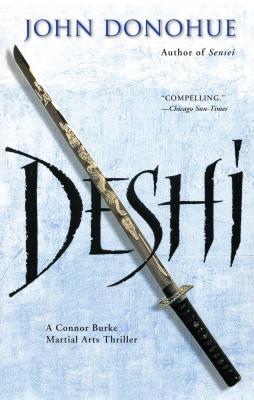

Deshi. John Donohue

Читать онлайн.Название Deshi

Год выпуска 0

isbn 9781594392481

Автор произведения John Donohue

Жанр Ужасы и Мистика

Серия A Connor Burke Martial Arts Thriller

Издательство Ingram

The breeze was warm that day and the air felt soft and laden with moisture. It was the time of year when a few good sunny hours could make the plants seem to explode with buds and blossoms. You could feel it: after a time of tense waiting, something was about to happen.

Edward Sakura knew about waiting. The people I spoke with told me that. He had learned to check the urge to act quickly with a calm, methodical discipline. The excitement and anticipation that were part of putting together a good deal never faded, of course. It was why he was in the business he was in. But he had mastered his impulses through years of trial and error. And it had paid off handsomely.

Shodo, the Way of the Brush, had been a constant teacher for over three decades in his quest for patience. It was one of life’s little ironies. As a young man, he had learned from his parents’ experience in Manzinar that safety in America was based on conforming to American culture. In retrospect, people of Sakura’s generation were puzzled as to why their folks did not grasp that one fact about America. After all, the Japanese themselves had a saying that the nail that sticks out gets banged down.

He had looked at the photos from the camps the American government had shunted his parents and other Japanese-Americans off to. The rows of slapdash wooden barracks, geometrically arranged in the desolation of the high American desert, would have been enough to drive the lesson home to even the dimmest of observers. And by the end of the war, Americans of Japanese descent had learned to look forward into the future, simply because the past was too painful. And, in so doing, they turned their gaze away from Japan.

Sakura had been a bright kid and he turned into an even brighter adult. After getting his MBA he had developed a taste for the high-octane deals increasingly being cut in the entertainment industry. And, over time, he succeeded quite well for himself. But with middle age, he had come to yearn for some sense of connection to his past. A high-energy man in a fast-paced business, he chose an endeavor diametrically opposed to the normal pace of his days.

For thirty years, every day, no matter where he was, Sakura surrendered part of his life to the Discipline of the Brush. As his teachers directed, he would set aside his worries. Enter a realm of a quiet focus. Then, kneeling before the purity of white paper, he would slowly, methodically prepare. The cake of dried ink would whir faintly against the stone as he ground it into powder. He would carefully add water to the mix, gazing intently at the liquid, thick with promise, dense and black with potential.

Then he would breathe, calming his hand, centering himself before picking up the brush. And, when spirit and brush were one, the ink trail would spool across the paper, leaving something of Sakura frozen in time, made manifest in the stark contrast of black ink and white background.

He had carried his art with him when he relocated to New York. The growing presence of Japanese companies like Sony in the entertainment industry meant that there were opportunities for a dealmaker like Sakura on two coasts. He worked in Manhattan and went home each night to a quiet, upscale neighborhood in the Fort Hamilton section of Brooklyn. It was a community that seemed tidy and green after the sprawling concrete of Manhattan. You could smell the sea in the breeze that blew in from the Atlantic. And best of all, amid the blush of life in a spring garden, it contained Sakura’s small Shodo hut.

He had built it as far back away from the house as he could. The property lines in his neighborhood were set with high walls for privacy and thickly cushioned with trees. It made for a small island of tranquility. He felt drawn to it now more than ever, a stone that sat, still and isolated, in the rushing current of his life.

The hut’s location was why he didn’t hear his killer approach.

In this part of Brooklyn, people value their privacy. The streets are relatively narrow, the houses old and well established, their faces closed to the street. The lots that the houses sit on are irregular, with occasional backyards of surprising depth. The hum of traffic from the more congested avenues to the east is never absent. And one more Lexus tooling sedately through the late afternoon streets would not have excited much comment.

People think of hunting as essentially a chase. But professional hunters, the really successful ones, get that way by wasting very little energy and planning ahead. They can chase if they have to, but they much prefer to stalk. And, if possible, they would rather use the techniques of ambush. Know your prey. Know his patterns. Know where he will be. And wait there.

Did the killer sneak up on Sakura or was he already there, lurking in the undergrowth? It doesn’t really matter. He knew where to find his victim. And with the pitiless certainty of all killers, he moved in.

The old masters, the real sensei, say that any Way leads to the same point. Whether you pick up the brush or the sword, the focus and training changes you. It’s imperceptible at first. But it is cumulative. I later studied Sakura’s calligraphy, and it told me that his three decades of training had not been wasted.

The whole point of calligraphy is to lose yourself in it, not dwell on distractions. It’s probable that he picked up on the sensations swirling around him, because mastering stillness means you can also vibrate like a tuning fork when conditions are right. I know. And I’ll bet Sakura did, too.

Professionals don’t leak much emotion. The Japanese warriors of old talked about the concept of remaining in kage, within the shadow or shade. You don’t give anything of yourself to your opponent. You don’t let enemies see what you think or feel or intend. The killer that day was probably as quiet and self-contained as they come. Yet we all leak some psychic energy, no matter how hard we try.

The atmosphere was charged with tension that day, and the victim sensed it. I work in a discipline with different tools, but the methods are the same. My teachers say that the mind can be distracted and “stick” to some extraneous thing. It creates a gap in your concentration. And you can see it revealed in subtle ways in your technique.

And that’s what I see when I look at that sheet of calligraphy from Edward Sakura. An intrusion. A change in focus.

The killer parked his car on the next block and walked back to the side gate that led to the rear of the property. He eventually had to leave the concrete and stone surface to get to his target, so he left a trace. His footprints through the rich, dark, spring earth suggested a big man. He walked slowly and quietly—the imprints are deeper on the toe and not much dirt was thrown backwards. There was no need for haste and no need to make noise. He obviously knew where he was going and knew what he would find there.

Sakura’s head probably came up as he sensed the killer’s approach. He remained seated in the formal position, legs tucked under him, insteps flat on the floor. The awareness must have come on him with an overwhelming finality. Not a thrill of panic or an electric jolt, but a deep-seated settling, like something at the body’s very core shifting down toward the earth, where it lodged, unmistakable and immovable.

There was no forced entry and none of the smashed doorjamb theatrics you might expect. There was no wasted motion. It was economical and efficient. You would almost call it civilized. Except for the end result.

The killer entered the hut from the door to the calligrapher’s left. Sakura shifted slightly to view the intruder, but remained oriented toward the low table that held his paper and brush. Did his eyes get wide as the attacker loomed there? I would have been scrambling around like mad. But there was none of that either.

Sakura knew about deals. He understood how they worked and how you could work them. But people who knew him also said he had the knack of analyzing things and predicting the outcome way before most other people. He knew when you could still negotiate and knew when the deal was done. So between the phenomenon the Japanese call haragei—a type of intuition common among masters of the arts—and his years of business acumen, Sakura pretty much knew what was about to happen. There was no way out.

There may have been some conversation. Not much. The killer was not in a line of work that did much to develop verbal skills. Messages got