ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

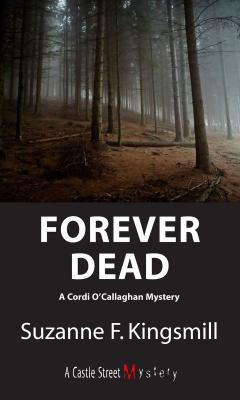

Forever Dead. Suzanne F. Kingsmill

Читать онлайн.Название Forever Dead

Год выпуска 0

isbn 9781554885367

Автор произведения Suzanne F. Kingsmill

Жанр Ужасы и Мистика

Серия A Cordi O'Callaghan Mystery

Издательство Ingram

“Jesus, Ryan, we’ll never make it!” I yelled, but my words were lost in the roaring of the raw power of the river. I looked ahead and stifled the panic building inside me.

The whole river ahead of me was torn up, shreds of water spewing everywhere, boiling, seething, and we were barrelling down toward that cauldron at a break-neck pace. Huge standing waves were breaking up in front of us, and two boulders were causing angry waves to jerk and thrash.

I gripped my paddle, eyeballed the river, and made a quick judgment, trying to remember what I had seen from the head of the rapids when we had joked about running them and I had thought about immortality. We would have to go right between the two boulders. Going left meant huge standing waves, and I could see water leaping up, the telltale signs of shallow water just beyond them. We’d never get by that. The boulders it would have to be, but we were too far right. We had to get the canoe over.

I thrust my paddle into the water, leaning way over the side of the canoe, and pulled the blade back toward the canoe to draw the bow to the left, waiting for Ryan to rudder the stern around to line us up so that we were pointed right between the boulders.

I could see the air bubbles churning over one of the rocks as the canoe swept down upon it, and just when I figured we were going to broadside Ryan pried the stern out and the canoe swept by the right boulder, missing it by inches.

I tried to remember what came after the boulders. What had Ryan pointed out? Hug the shore, take the ledge on the right, and eddy out before the waterfalls — or was it take the ledge on the left? I couldn’t remember what path to take. Everything looked so different now we were in the rapids.

Just ahead and to our right a jagged rock suddenly reared out of the water. I hoped I was right: we needed to go to the right of it, to give us a good chance of avoiding the ledge. I started paddling to draw the bow to the right, but the current was too fast and I frantically switched sides and pulled the bow left to avoid broad siding the rock. Ryan took my lead and we flew by on the wrong side.

We were in the centre of the rapids now, heading for the shelf, which I still couldn’t see. The foam and the spray washed over me as I strained to pick out our route.

And then, suddenly, I saw it: the long, low uninterrupted line of the shelf. We were too far to the right. We were on a collision course.

“Left!” I screamed into the wind, frantically leaning way out and pulling my paddle in toward the canoe to pull the bow over. The clamour of the rapids killed all other sound and my words were whipped away on the wind, but I knew, as long as Ryan was watching, that the meaning in my wildly pumping arms made it very clear just exactly what was expected of him.

Ryan held the canoe angled, with the bow pointing to shore, and it looked to me like we would broadside. I jabbed my paddle again and again into the churning white mess, blade parallel to the canoe and as far out as I dared reach, then hauled back on it to draw the bow forward and to the left. My arms screamed for rest and my jaw ached from being clamped tight while my adrenaline raced the river for how fast it could drown me. The bow was clear, but it was touch and go if I was really clear enough for Ryan to start bringing the stern around. If he did a strong pry too soon, the canoe would swing around and we would hit the shelf. He held off till the last possible minute and then, with a mighty pry, the stern swung around and the canoe shot past the shelf, so close that I could see the flecks of quartz on the rocks that would have claimed us.

I could see the churning cauldron to my left and the easy, smooth, fast-running water to my right, but to get to it we had to go to the right of a big boulder fast approaching. We had shipped some water, and the canoe was sluggish and not responding as quickly to steering. We hit side on.

The canoe tilted crazily. I reached out and slapped the water hard with the flat side of the paddle blade. The canoe came upright, shipping water as it entered a rolling field of haystacks, huge standing waves sculpted by the hidden boulders beneath. We back paddled to keep the canoe riding the waves.

The eddy we had seen from the shore had to be somewhere ahead, somewhere we could take out — had to take out before the falls. And suddenly there it was, the big boulder and beyond and to its side the small square of dead water and safety. But to my horror, straddling the rock and pushing out over the water to block our route was a “sweeper,” a great bloody pine tree, partly submerged.

If we hit it broadside the canoe would tip and fill. We’d be swept under and held by the sweeper. But there was no time to go around it. If we hit the sweeper bowon I could leap onto it, if it held, but Ryan would swing around or, worse, dump as I leapt.

Broadside it would have to be. We would have to leap in unison, just before it hit. I made the decision, drawing frantically to pull the bow around as Ryan pried, hoping to God we could time it right, that Ryan was reading my signals properly. I braced myself as the canoe hit broadside, flinging my weight downriver to counteract the canoe’s crazy tilt upstream into the current. I could see Ryan, closer to shore, flinging his body onto the tree, even as I felt my hands close around a limb. I felt the branches beneath me ripping through my shirt as I grabbed the ones on the surface and then felt the weight of my body dragging them into the water, its power slamming into me like a freight train. I could feel my grip slipping as the water grabbed my legs, pulling them down, dragging me with them. I felt the canoe broach, felt my hands slip. I grabbed wildly for another branch and struggled as my legs were pulled along by the water. I hung on desperately, but the branch was pliable, soft, and my weight pulled it under; I felt my body being pulled under the branches, still with their needles untarnished by death, and then my momentum stopped suddenly as I was jerked back by the straps of my pack.

I was face up and felt like a pinned insect amongst the submerged branches of the tree, barely able to breathe as the water sluiced over my face. I was afraid to move, for fear the backpack would suddenly let go, my left hand in a rigid grip on a small branch, my right hand and arm pressed up against another branch. I stayed as still as I could and waited. Where was Ryan?

I could feel my energy dwindling away as the force of the water pounded me mercilessly. And then he was there above me on the main tree trunk, reaching down, touching my face. I could see his lips moving but heard nothing, just felt the water pressing hard against my ears like a vice; I couldn’t move my head in any direction, as it was braced by the water on both sides and was being pushed down against the ominously flimsy branches beneath. Ryan said something again but it was useless — I couldn’t hear him and suddenly he was gone.

I timed my breathing to coincide with the least amount of water sluicing over me, terrified that I would start to choke. I felt the panic in me begin to rise and forced myself to think of something else.

And then Ryan was back and I watched as he pulled out his knife and cut the end off a plastic Coke bottle. He reached over and indicated that he wanted me to breathe through it. I started to lose it. I was sure I was going to drown, the bottle would be wrenched from my mouth by the power of the water and I’d be gone. Ryan grabbed my free hand and pressed it, and then pointed to the sturdy branch right above my head. He placed the bottle upriver of it and fed it into my mouth so that the branch braced the bottle. I clamped down with my teeth on the rim of the bottle and took a tentative breath through the tube, fearing water, getting air.

Ryan disappeared for what seemed like hours. The water was sluicing constantly now over my face, and my teeth ached from their iron grip around the bottle. Suddenly I felt Ryan’s nails digging into my hands.

“Cordi, can you hold on?” he yelled over the raging of the river. He was gone and then was back with a coil of rope, one end of which he tied with a bowline to one of the tree’s branches that soared out of the water. Struggling, he lay over the partially submerged trunk and reached down into the lunging strength of the current. After what seemed like an interminable amount of fumbling he finally got the other end of the rope under my arms and tied another bowline.

“I’ll