ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

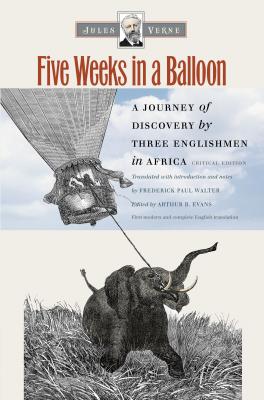

Five Weeks in a Balloon. Jules Verne

Читать онлайн.Название Five Weeks in a Balloon

Год выпуска 0

isbn 9780819575487

Автор произведения Jules Verne

Жанр Научная фантастика

Серия Early Classics of Science Fiction

Издательство Ingram

So a complete, accurate, reader-friendly translation of Verne’s early masterpiece is long overdue. This book has a twofold audience: first, the countless general readers who think Verne is fun to read, a population ranging from school kids to scientists to oldsters with fond memories. This new translation is particularly meant for them and works to balance the two methodologies Kieran O’Driscoll describes in his recent study of Verne in English: in brief, my text began life as a “highly accurate, source-oriented, imitative” rendering, which I then polished using “informal, idiomatic language” (251–52). As for other audience members, they include the growing battalions of scholars and specialists who, although they know their Verne from the original French, are still appreciative of textual detective work and stimulating critical materials. I encourage them to consult the endnotes, which address the policies, priorities, textual puzzles, and interpretive decisions affecting the translation. In short, to borrow another of O’Driscoll’s phrases, this new, complete rendering of Five Weeks in a Balloon is “aimed at both a general and a scholarly readership” (190).

Frederick Paul Walter Albuquerque, New Mexico

REFERENCES

Butcher, William. Jules Verne: The Definitive Biography. New York: Thunder’s Mouth, 2006.

Compère, Daniel. Jules Verne: Écrivain. Geneva: Librairie Droz, 1991.

Costello, Peter. Jules Verne: Inventor of Science Fiction. New York: Scribner’s, 1978.

Dale, Henry. Early Flying Machines. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992.

Dehs, Volker. “Les Manuscrits de Cinq semaines en ballon.” Bulletin de la Société Jules Verne, no. 183 (August 2013): 20–27.

Denniston, George. The Joy of Ballooning. Philadephia: Courage Books, 1999.

Deschamps, Jean-Marc. Jules Verne: 140 ans d’inventions extraordinaires. Paris: Du May, 2005.

Disraeli, Benjamin. Letters: 1860–1864. Edited by M. G. Wiebe, Mary S. Millar, Ann P. Robson, and Ellen L. Hawman. Toronto: University of Toronto, 2009.

Evans, Arthur B. “The English Editions of Five Weeks in a Balloon.” Verniana 6 (2013–14): 141–70.

———. Jules Verne Rediscovered: Didacticism and the Scientific Novel. New York: Greenwood, 1988.

———. “Jules Verne’s English Translations.” Science Fiction Studies 32, no. 1 (March 2005): 80–104.

Fernández-Armesto, Felipe. Pathfinders: A Global History of Exploration. New York: Norton, 2006.

Froidefond, Alain. “Jules Verne fabuleux.” In Jules Verne, no. 8: Humour, ironie, fantasie. Edited by Christian Chelebourg. Paris: Lettres Modernes Minard, 2003.

Habeeb, William Mark. Africa: Facts and Figures. Philadelphia: Mason Crest, 2005.

Hallion, Richard P. Taking Flight: Inventing the Aerial Age from Antiquity through the First World War. New York: Oxford University Press, 2003.

Jules-Verne, Jean. Jules Verne: A Biography. Translated and adapted by Roger Greaves. New York: Taplinger, 1976.

Lottman, Herbert R. Jules Verne: An Exploratory Biography. New York: St. Martins Press, 1996.

Martell, Hazel Mary. Exploring Africa. New York: Peter Bedrick, 1997.

Martin, Andrew. The Mask of the Prophet: The Extraordinary Fictions of Jules Verne. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1990.

Miller, Walter James. The Annotated Jules Verne: From the Earth to the Moon. 1978. 2nd ed. New York: Gramercy Books, 1995.

Noiray, Jacques. Le Romancier et la machine: L’image de la machine dans le roman français, 1850–1900, vol. 2. Paris: Corti, 1992.

O’Driscoll, Kieran. Retranslation through the Centuries: Jules Verne in English. Oxford: Peter Lang, 2011.

Owen, David. Lighter than Air: An Illustrated History of the Development of Hot-air Balloons and Airships. Edison, NJ: Chartwell, 1999.

Quinn, Arthur Hobson. Edgar Allan Poe: A Critical Biography. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1941. Pbk. ed., 1998.

Voisin, Marcel. “Théophile Gautier: Précurseur de Jules Verne?” In Colloque d’Amiens (1977), vol. 2: Jules Verne: Filiations.Rencontres.Influences. Paris: Lettres Moderne Minard, 1980.

Walter, Frederick Paul. Amazing Journeys: Five Visionary Classics by Jules Verne. Albany: State University of New York Press, 2010.

chapter 1

The end of a wildly applauded speech—introducing Dr. Samuel Fergusson—“Excelsior”—full-length portrait of the doctor—a confirmed fatalist—dinner at the Travelers Club—many toasts to the occasion.

They had a packed house for the Royal Geographical Society’s meeting on January 14, 1862, at 3 Waterloo Place, London. Their president, Sir Francis M——, made a major announcement to his distinguished colleagues during a speech that was frequently interrupted by cheering.

This choice bit of eloquence finally came to a close with several grandiose sentences brimming over with patriotic fervor:

“England has always marched in front of other nations” (because, mind you, nations are always marching on each other’s fronts), “thanks to the valor of her explorers in the realm of geographical discovery. (Much agreement.) Dr. Samuel Fergusson, one of her glorious sons, won’t disgrace his ancestry. (No’s from all directions.) If this endeavor succeeds (It will!) we’ll ultimately fill in the blank spaces on Africa’s map (hearty approval), and if it fails (No, never!) at the very least it will go down as one of the most courageous expressions of the human spirit!” (Frenzied stamping of feet.)

“Hooray! Hooray!” the gathering shouted, galvanized by these rousing words.

“Hooray for Fergusson the fearless!” exclaimed one of the audience’s noisier members.

Enthusiastic yells rang out. Fergusson’s name burst from every mouth, and we have reason to believe that it got an extra oomph from passing through English throats. The meeting room shook.

Yet many in the audience were seasoned travelers, dauntless, weather-beaten oldsters whose restless personalities had led them into the five corners of the globe! Mentally or physically, one way or another, they all had survived shipwrecks, wildfires, Indian tomahawks, the war clubs of savages, burning at the stake, and the bellies of Polynesians! But nothing could quiet their pounding hearts during that speech by Sir Francis M——, which was definitely the grandest oratorical success at London’s Royal Geographical Society within living memory.

But in England enthusiasm is more than a matter of words. It generates money quicker than molds at the Royal Mint.* They voted Dr. Fergusson a performance incentive on the spot, the lofty figure of £2500.1 The significance of the sum was in keeping with the significance of