ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

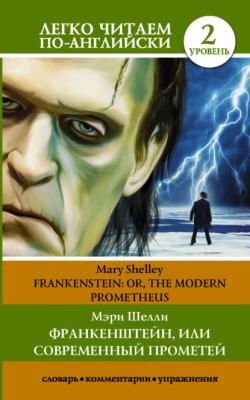

Франкенштейн, или Современный Прометей / Frankenstein, or The Modern Prometheus. Уровень 2. Мэри Шелли

Читать онлайн.Название Франкенштейн, или Современный Прометей / Frankenstein, or The Modern Prometheus. Уровень 2

Год выпуска 1817

isbn 978-5-17-144930-8

Автор произведения Мэри Шелли

Жанр Ужасы и Мистика

Серия Легко читаем по-английски

Издательство Издательство АСТ

“You are all mistaken; I know the murderer. Justine, poor, good Justine, is innocent.”

At that instant my father entered. Ernest exclaimed,

“Good God, papa! Victor says that he knows who was the murderer of poor William.”

“We do also, unfortunately,” replied my father, “and I prefer to be ignorant than to see so much depravity and ungratitude in that girl.”

“My dear father, you are mistaken; Justine is innocent.”

“If she is, God will help her. She will be tried today.”

This speech calmed me. I was firmly convinced that Justine was guiltless of this murder.

Soon Elizabeth joined us. She welcomed me with the greatest affection.

“Your arrival, my dear cousin,” said she, “fills me with hope. You perhaps will find some means to justify poor guiltless Justine. Alas! I believe in her innocence. If she is condemned[17], I never shall know joy more. But she will not, I am sure. She will not; and then I shall be happy again, even after the sad death of my little William.”

“She is innocent, my Elizabeth,” said I, “fear nothing!”

“How kind and generous you are! Every one believes in her guilt, and that makes me sad. I know that it is impossible.” She wept.

“Dearest niece,” said my father, “dry your tears. If she is, as you believe, innocent, rely on the justice of our laws.”

Chapter 8

We passed a few sad hours until eleven o’clock, when the trial began. My father and the rest of the family were witnesses. I accompanied them to the court. Justine was a girl of merit; now she will be tried, and I am the cause!

Justine was calm. She was dressed in mourning[18], her face was solemn and beautiful. She did not tremble, although people looked at her with hatred. She was tranquil, and her tranquillity was a proof of her guilt. When she entered the court she looked around and quickly discovered where we were. A tear dimmed her eye when she saw us, but she quickly recovered herself.

The trial began, several witnesses spoke. Several strange facts combined against her. She was out that night. In the morning a market-woman perceived her not far from the spot where the body of the murdered child was. The woman asked her what she did there, but she looked very strangely and only returned a confused and unintelligible answer. She returned to the house about eight o’clock. When she saw the body, she fell into violent hysterics and was ill for several days. Then the servant found the picture in her pocket. Elizabeth proved that it was the same which was round the child’s neck. Elizabeth herself gave it to the boy! A murmur of horror and indignation filled the court.

Justine’s countenance altered. It expressed surprise, horror, and misery. Sometimes Justine struggled with her tears, but she collected her powers and spoke.

“God knows,” she said, “how entirely I am innocent. I want to give a simple explanation of the facts which are against me.”

She then related that, by the permission of Elizabeth, she passed the evening at the house of an aunt at Chene, a village near Geneva. On her return, at about nine o’clock, she meets a man. That man asks her if she saw the child who was lost. She was alarmed and began to looking for the boy. The gates of Geneva were shut, and she remained several hours of the night in a barn. Most

of the night she did not sleep. In the morning some steps disturbed her, and she awoke. It was dawn, and she quitted her asylum. She wanted to find my brother. If she went near the spot where his body lay, it was without her knowledge. What about the picture? She could give no answer.

“I know,” continued the unhappy victim, “how heavily and fatally this picture weighs against me. But I can’t explain it. Somebody placed it in my pocket. But who? I have no enemies. Did the murderer place it there? But when? And if he stole the jewel, why part with it again so soon?

I see no hope. I can say only this: I am totally innocent.”

Several witnesses spoke well of her; but fear and hatred of the crime rendered them timorous. Elizabeth desired permission to address the court.

“I am,” said she, “the cousin of the unhappy child who was murdered, or rather his sister. And I see a poor girl who is about to perish through the cowardice of her pretended friends. I may say what I know of her character. I am well acquainted with the accused. I have lived in the same house with her, at one time for five and at another for nearly two years. During all that period she appeared to me the most amiable and benevolent of human creatures. She nursed Madame Frankenstein, my aunt, in her last illness, with the greatest affection and care. Afterwards she attended her own mother during a tedious illness. After that she again lived in my uncle’s house, where all the family loved her. She was warmly attached to the child who is now dead and acted like a mother. I do not hesitate to say that, notwithstanding all the evidence against her, I believe and rely on her perfect innocence. She had no temptation for such an action. I esteem and value her much.”

A murmur of approbation followed Elizabeth’s simple and powerful appeal. Anyway, the audience charged poor Justine with the blackest ingratitude. Justine herself wept as Elizabeth spoke, but she did not answer. My own agitation and anguish was extreme during the whole trial. I believed in her innocence; I knew it. Could the demon who murdered (I did not doubt) my brother betray the innocent to death and ignominy? I could not sustain the horror of my situation, and I rushed out of the court in agony. The fangs of remorse tore my bosom.

In the morning I went to the court; my lips and throat were parched. I dared not ask the fatal question. The officer guessed the cause of my visit. Justine was condemned.

I cannot describe what I then felt. The officer added that Justine already confessed her guilt.

This was strange and unexpected; what could it mean? Did my eyes deceive me? I hastened to return home.

“My cousin,” replied I, “she has confessed.”

This was a dire blow to poor Elizabeth, who relied upon Justine’s innocence.

“Alas!” said she. “How shall I ever again believe in human goodness? Justine, whom I loved and esteemed as my sister! Her mild eyes seemed incapable of any severity or guile, and yet she has committed a murder.”

Soon after we heard that the poor victim expressed a desire to see my cousin.

“Yes,” said Elizabeth, “I will go, although she is guilty. And you, Victor, will accompany me. I cannot go alone.”

The idea of this visit was torture to me, yet I could not refuse.

We entered the gloomy prison chamber and beheld Justine. She was sitting on some straw at the farther end. Her hands were manacled, and her head rested on her knees. She rose, and when we were left alone with her, she threw herself at the feet of Elizabeth. She wept bitterly. My cousin wept also.

“Oh, Justine!” said she. “I relied on your innocence! I was not so miserable as I am now.”

“And do you also believe that I am so very, very wicked? Do you also join with my enemies to crush me, to condemn me as a murderer?” Her voice was suffocated with sobs.

“Rise, my poor girl,” said Elizabeth; “why do you kneel, if you are innocent? I am not one of your enemies. I believed you were guiltless, notwithstanding every evidence, until I heard that you yourself declared your guilt. That report, you say, is false. Dear Justine, nothing can shake my confidence in you, but your own confession.”

“I confessed, but I confessed a lie. I confessed to obtain absolution. But now that falsehood lies heavier at my heart than all my other sins. God will forgive me! My confessor besieged me; he threatened and menaced, until I almost began to think that I was the monster that he said I was. He threatened excommunication and hell fire if I continued obdurate. Dear lady,

if she is condemned – если её осудят

in mourning – в трауре