ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

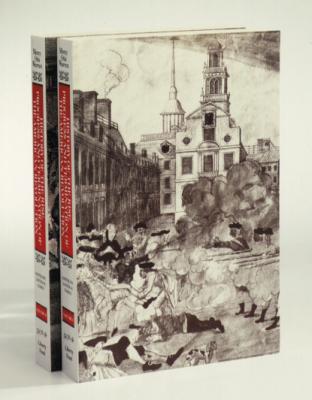

History of the Rise, Progress, and Termination of the American Revolution. Mercy Otis Warren

Читать онлайн.Название History of the Rise, Progress, and Termination of the American Revolution

Год выпуска 0

isbn 9781614871392

Автор произведения Mercy Otis Warren

Издательство Ingram

With regard to the rest of your Excellency’s speech, we are constrained to observe, that the general air and style of it favors much more of an act of free grace and pardon, than of a parliamentary address to the two houses of assembly; and we most sincerely with your excellency had been pleased to reserve it, if needful, for a proclamation.

In the bill for compensation by the assembly of Massachusetts, was added a very offensive clause. A general pardon and oblivion was granted to all offenders in the late confusion, tumults and riots. An exact detail of these proceedings was transmitted to England. The king and council disallowed the act, as comprising in it a bill of indemnity to the Boston rioters, and ordered compensation made to the late sufferers, without any supplementary conditions. No notice was taken of this order, nor any alteration made in the act. The money was drawn from the treasury of the province to satisfy the claimants for compensation, and no farther inquiries were made relative to the authors of the late tumultuary proceedings of the times, when [37] the minds of men had been wrought up to a ferment, beyond the reach of all legal restraint.

The year one thousand seven hundred and sixty-six had passed over without any other remarkable political events. All colonial measures agitated in England were regularly transmitted by the minister for the American department to the several plantation governors; who, on every communication endeavoured to enforce the operation of parliamentary authority, by the most sanguine injunctions of their own, and a magnificent display of royal resentment, on the smallest token of disobedience to ministerial requisitions. But it will appear, that through a long series of resolves and messages, letters and petitions, which passed between the parties, previous to the commencement of hostilities, the watchful guardians of American freedom never lost sight of the intrigues of their enemies, or the mischievous designs of such as were under the influence of the crown, on either side the Atlantic.

It may be observed, that the tranquillity of the provinces had for some time been interrupted by the innovating spirit of the British ministry, instigated by a few prostitutes of power, nurtured in the lap of America, and bound by every tie of honor and gratitude, to be faithful to the interests of their country. The social enjoyments of life had long been disturbed, the mind fretted, and the people rendered suspicious, [38] when they saw some of their fellow citizens, who did not hesitate at a junction with the accumulated swarms of hirelings, sent from Great Britain to ravish from the colonies the rights they claimed both by nature and by compact. That the hard hearted judges of admiralty, and the crowd of revenue officers, that hovered about the custom houses, should seldom be actuated by the principles of justice, is not strange. Peculation was generally the prime object of this class, and the oaths they administered, and the habits they encouraged, were favorable to every species of bribery and corruption. The rapacity which instigated these descriptions of men had little check, while they saw themselves upheld even by some governors of provinces. In this grade, which ought ever to be the protectors of the rights of the people, there were some, who were total strangers to all ideas of equity, freedom, or urbanity. It was observed at this time, in a speech before the house of commons, by colonel Barre, that, “to his certain knowledge, some were promoted to the highest seats of honor in America, who were glad to fly to a foreign country, to escape being brought to the bar of justice in their own.”*

However injudicious the appointments to American departments might be, the darling [39] point of an American revenue was an object too consequential to be relinquished, either by the court at St. James’s, the plantation governors, or their mercenary adherents dispersed through the continent. Besides these, there were several classes in America, who were at first exceedingly opposed to measures that militated with the designs of administration;—some impressed by long connexion, were intimidated by her power, and attached by affection to Britain. Others, the true disciples of passive obedience, had real scruples of conscience with regard to any resistance to the powers that be; these, whether actuated by affection or fear, by principle or interest, formed a close combination with the colonial governors, custom-house officers, and all in subordinate departments, who hung on the court for subsistence. By the tenor of the writings of some of these, and the insolent behaviour of others, they became equally obnoxious in the eyes of the people, with the officers of the crown, and the danglers for place; who, disappointed of their prey by the repeal of the stamp-act, and restless for some new project that might enable them to rise into importance, on the spoils of America, were continually whispering malicious insinuations into the ears of the financiers and ministers of colonial departments.

They represented the mercantile body in America as a set of smugglers, forever breaking over the laws of trade and of society; the [40] people in general as factious, turbulent, and aiming at independence; the legislatures in the several provinces, as marked with the same spirit, and government every where in so lax a state, that the civil authority was insufficient to prevent the fatal effects of popular discontent.

It is indeed true, that resentment had in several instances arisen to outrage, and that the most unwarrantable excesses had been committed on some occasions, which gave grounds for unfavorable representations. Yet it must be acknowledged, that the voice of the people seldom breathes universal murmur, but when the insolence or the oppression of their rulers extorts the bitter complaint. On the contrary, there is a certain supineness which generally overspreads the multitude, and disposes mankind to submit quietly to any form of government, rather than to be at the expense and hazard of resistance. They become attached to ancient modes by habits of obedience, though the reins of authority are sometimes held by the most rigorous hand. Thus we have seen in all ages the many become the slaves of the few; preferring the wretched tranquillity of inglorious ease, they patiently yield to despotic masters, until awakened by multiplied wrongs to the feelings of human nature; which when once aroused to a consciousness of the native freedom and equal rights of man, ever revolts at the idea of servitude.

[41] Perhaps the story of political revolution never exhibited a more general enthusiasm in the cause of liberty, than that which for several years pervaded all ranks in America, and brought forward events little expected by the most sanguine spirits in the beginning of the controversy. A contest now pushed with so much vigour, that the intelligent yeomanry of the country, as well as those educated in the higher walks, became convinced that nothing less than a systematical plan of slavery was designed against them. They viewed the chains as already forged to manacle the unborn millions; and though every one seemed to dread any new interruption of public tranquillity, the impetuosity of some led them into excesses which could not be restrained by those of more cool and discreet deportment. To the most moderate and judicious it soon became apparent, that unless a timely and bold resistance prevented, the colonists must in a few years sink into the same wretched thraldom, that marks the miserable Asiatic.

Few of the executive officers employed by the king of Great Britain, and fewer of their adherents, were qualified either by education, principle, or inclination, to allay the ferment of the times, or to eradicate the suspicions of men, who, from an hereditary love of freedom, were tenderly touched by the smallest attempt, to undermine the invaluable possession. Yet, perhaps [42] few of the colonies, at this period, suffered equal embarrassments with the Massachusetts. The inhabitants of that province were considered as the prime leaders of faction, the disturbers of public tranquillity, and Boston the seat of sedition. Vengeance was continually denounced against that capital, and indeed the whole province, through the letters, messages, and speeches of their first magistrate.

Unhappily for both parties, governor Bernard was very illy calculated to promote the interest of the people, or support the honor of his master. He was a man of little genius, but some learning. He was by education strongly impressed with high ideas of canon and feudal law, and fond of a system of government that had been long obsolete in England, and had never had an existence in America. His disposition was choleric and sanguine, obstinate and designing, yet too open and frank to disguise his intrigues, and too precipitant to bring them to maturity. A revision of colony charters, a resumption of former privileges, and an American revenue, were the constant topics of his letters to administration.*