ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

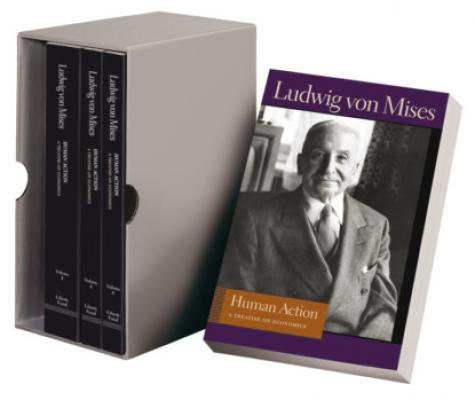

Human Action. Людвиг фон Мизес

Читать онлайн.Название Human Action

Год выпуска 0

isbn 9781614871477

Автор произведения Людвиг фон Мизес

Жанр Зарубежная деловая литература

Серия Liberty Fund Library of the Works of Ludwig von Mises

Издательство Ingram

In order to avoid any possible misinterpretation of the praxeological categories it seems expedient to emphasize a truism.

Praxeology, like the historical sciences of human action, deals with purposeful human action. If it mentions ends, what it has in view is the ends at which acting men aim. If it speaks of meaning, it refers to the meaning which acting men attach to their actions.

Praxeology and history are manifestations of the human mind and as such are conditioned by the intellectual abilities of mortal men. Praxeology and history do not pretend to know anything about the intentions of an absolute and objective mind, about an objective meaning inherent in the course of events and of historical evolution, and about the plans which God or Nature or Weltgeist or Manifest Destiny is trying to realize in directing the universe and human affairs. They have nothing in common with what is called philosophy of history. They do not, like the works of Hegel, Comte, Marx, and a host of other writers, claim to reveal information about the true, objective, and absolute meaning of life and history.11

Some philosophies advise men to seek as the ultimate end of conduct the complete renunciation of any action. They look upon life as an absolute evil full of pain, suffering, and anguish, and apodictically deny that any purposeful human effort can render it tolerable. Happiness can be attained only by complete extinction of consciousness, volition, and life. The only way toward bliss and salvation is to become perfectly passive, indifferent, and inert like the plants. The sovereign good is the abandonment of thinking and acting.

Such is the essence of the teachings of various Indian philosophies, especially of Buddhism, and of Schopenhauer. Praxeology does not comment upon them. It is neutral with regard to all judgments of value and the choice of ultimate ends. Its task is not to approve or to disapprove, but to describe what is.

The subject matter of praxeology is human action. It deals with acting man, not with man transformed into a plant and reduced to a merely vegetative existence.

The Epistemological Problems of the Sciences of Human Action

There are two main branches of the sciences of human action: praxeology and history.

History is the collection and systematic arrangement of all the data of experience concerning human action. It deals with the concrete content of human action. It studies all human endeavors in their infinite multiplicity and variety and all individual actions with all their accidental, special, and particular implications. It scrutinizes the ideas guiding acting men and the outcome of the actions performed. It embraces every aspect of human activities. It is on the one hand general history and on the other hand the history of various narrower fields. There is the history of political and military action, of ideas and philosophy, of economic activities, of technology, of literature, art, and science, of religion, of mores and customs, and of many other realms of human life. There is ethnology and anthropology, as far as they are not a part of biology, and there is psychology as far as it is neither physiology nor epistemology nor philosophy. There is linguistics as far as it is neither logic nor the physiology of speech.1

The subject matter of all historical sciences is the past. They cannot teach us anything which would be valid for all human actions, that is, for the future too. The study of history makes a man wise and judicious. But it does not by itself provide any knowledge and skill which could be utilized for handling concrete tasks.

The natural sciences too deal with past events. Every experience is an experience of something passed away; there is no experience of future happenings. But the experience to which the natural sciences owe all their success is the experience of the experiment in which the individual elements of change can be observed in isolation. The facts amassed in this way can be used for induction, a peculiar procedure of inference which has given pragmatic evidence of its expediency, although its satisfactory epistemological characterization is still an unsolved problem.

The experience with which the sciences of human action have to deal is always an experience of complex phenomena. No laboratory experiments can be performed with regard to human action. We are never in a position to observe the change in one element only, all other conditions of the event remaining unchanged. Historical experience as an experience of complex phenomena does not provide us with facts in the sense in which the natural sciences employ this term to signify isolated events tested in experiments. The information conveyed by historical experience cannot be used as building material for the construction of theories and the prediction of future events. Every historical experience is open to various interpretations, and is in fact interpreted in different ways.

The postulates of positivism and kindred schools of metaphysics are therefore illusory. It is impossible to reform the sciences of human action according to the pattern of physics and the other natural sciences. There is no means to establish an a posteriori theory of human conduct and social events. History can neither prove nor disprove any general statement in the manner in which the natural sciences accept or reject a hypothesis on the ground of laboratory experiments. Neither experimental verification nor experimental falsification of a general proposition is possible in its field.

Complex phenomena in the production of which various causal chains are interlaced cannot test any theory. Such phenomena, on the contrary, become intelligible only through an interpretation in terms of theories previously developed from other sources. In the case of natural phenomena the interpretation of an event must not be at variance with the theories satisfactorily verified by experiments. In the case of historical events there is no such restriction. Commentators would be free to resort to quite arbitrary explanations. Where there is something to explain, the human mind has never been at a loss to invent ad hoc some imaginary theories, lacking any logical justification.

In the field of human history a limitation similar to that which the experimentally tested theories enjoin upon the attempts to interpret and elucidate individual physical, chemical, and physiological events is provided by praxeology. Praxeology is a theoretical and systematic, not a historical, science. Its scope is human action as such, irrespective of all environmental, accidental, and individual circumstances of the concrete acts. Its cognition is purely formal and general without reference to the material content and the particular features of the actual case. It aims at knowledge valid for all instances in which the conditions exactly correspond to those implied in its assumptions and inferences. Its statements and propositions are not derived from experience. They are, like those of logic and mathematics, a priori. They are not subject to verification or falsification on the ground of experience and facts. They are both logically and temporally antecedent to any comprehension of historical facts. They are a necessary requirement of any intellectual grasp of historical events. Without them we should not be able to see in the course of events anything else than kaleidoscopic change and chaotic muddle.

2 The Formal and Aprioristic Character of Praxeology

A fashionable tendency in contemporary philosophy is to deny the existence of any a priori knowledge. All human knowledge, it is contended, is derived from experience. This attitude can easily be understood as an excessive reaction against the extravagances of theology and a spurious philosophy of history and of nature. Metaphysicians were eager to discover by intuition moral precepts, the meaning of historical evolution, the properties of soul and matter, and the laws governing physical, chemical, and physiological events. Their volatile speculations manifested a blithe disregard for matter-of-fact knowledge. They were convinced that, without reference to experience, reason could explain all things and answer all questions.

The