ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

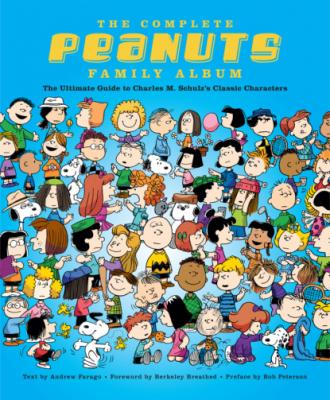

The Complete Peanuts Family Album. Andrew Farago

Читать онлайн.Название The Complete Peanuts Family Album

Год выпуска 0

isbn 9781681887531

Автор произведения Andrew Farago

Жанр Юмористические стихи

Издательство Ingram

one celebrated in this volume. It’s the business I made my

own not much after the above detour in preadolescent

entertainment choices, and Charles Schulz’s characters

played a role, not surprisingly. To be in cartooning is to

really be in “charactooning”—my term (I have no idea

where “car” came from). The comic strips—or movies, or

TV shows, or plays, or novels—that slip from memory

do so for one simple reason that you may test at will: The

personalities that inhabited these ephemeral vehicles were

forgettable.

Character doesn’t just count in comic strips; character

is everything. Making even just a few of them distinct, fun,

separate, and memorable when you only have four tiny

frames each day is a herculean feat. Making dozens and

dozens of them so is something else. Sparky Schulz did that.

Consider just one from Peanuts: my

favorite, Lucy. From the position of a

male writer who does this for a living,

I can tell you that it’s hard to create a

female character without stumbling back

on cliché. Lucy was wildly, wickedly

free from the usual feminine banalities

that girl characters attract like dumb

lumbering bears to honey. She was the

primary female character in Peanuts

and by far the most complex in the

whole gang. When Sparky invented the

very simple allegory of the held (and

inevitably withdrawn) football from the

ever-hopeful Charlie Brown, he brought

comic strips—and their real place in literature—into a

larger world where complex character, as it should, rules.

They gave Bob Dylan a Nobel Prize but neglected Charles

Schulz. That’s almost a punchline.

Peanuts wasn’t a collection of gags (like most comic

strips). It was an assemblage of personalities poured

happily from the mind of one that very skillfully hid his

creative, jubilant schizophrenia behind a genial smile and

a straightforward heart. In 1986, I lay in a hospital bed

with a broken spine after cracking up a small plane . . .

and I opened a package that included a very rare Peanuts

original strip, signed: To Berkeley with friendship & every

best wish—Sparky.

“With friendship.” I’d never met him. Character counts,

indeed. In Sparky’s case, his characters—in all their flaws

and passions and idiosyncrasies—gave a collective voice

to his own character of deep and undisguised humanity.

Explore them here in The Complete Peanuts Family Album

and marvel, like me, that they all came from one creative id.

I wish I’d known him better when I had the chance.

This volume may be the next best thing.

above: Outland strip by Berkeley Breathed | opposite: Design by Cameron + Co

I

went as Charlie Brown for Halloween this past year.

At age fifty-six, I got a few sideways glances. My beard

and glasses with my Charlie Brown bald wig made me look

more like Sigmund Freud Charlie. But I didn’t care. The

whole universe of Peanuts characters that Schulz created is

sacred to me. I remember being in my pajamas as a four-

year-old watching the Christmas special when it first ran

on TV. I read every Peanuts book I could. I identified with

Charlie Brown’s insecurities. I was amazed at the secret,

adventurous world of Snoopy. I was inspired by the spiri-

tuality of Linus and that he could endure the fussbudgetry

of Lucy! I coughed on the sidewalk and then stomped on

the germs. Schulz’s work is in my artistic DNA now. He has

many lessons for us.

Peanuts is such an interesting mix of emotional angst

and surrealism. Somehow the two go together. Who among

us hasn’t felt that the world becomes surreal during times

of angst? I’ve taken that Schulzian idea into my cartooning

and animation career, which includes twenty-three years as

a story artist and screenwriter at Pixar.

In graduate school at Purdue University, I drew a

daily four-panel strip called Loco Motives for the Purdue

Exponent Newspaper. There, I was exploring the angst of

university life but overlaid with a surreal set of characters

including a herbivorous plains-dwelling antelope who just

happened to live with two dudes on campus. Blitzen, as I

called him, could talk, and his antlers (much like Snoopy’s)

could reshape and reflect his emotions. There was no

reason for putting this character in, but I was inspired by

how Snoopy’s surreal world of flying aces and bowling

alleys in his dog house paired nicely with a normal round-

headed boy who found the world mean and indecipherable.

This duality also inspired me on movies like Up, which

is a mix of the grief of Carl Fredriksen and the surrealism

of talking dogs (“Squirrel!”). The two balance and clarify

each other. It seemed like the lower we took Carl in grief,

the more outlandish we could go with Dug and the rest of

the dog pack. Carl’s grief stood out in stark contrast. His

character was clear.

Which is another Schulz lesson: clarity and contrast of

character—we all know what Lucy or Schroeder or Sally

would say or do in any situation. It’s what we in storytelling

grapple with, and I am daily inspired by Schulz’ mastery of

it. In Monsters, Inc., we spent a lot of time at the beginning

just trying to define how Mike Wazowski would contrast

Sulley. As an exercise,