ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

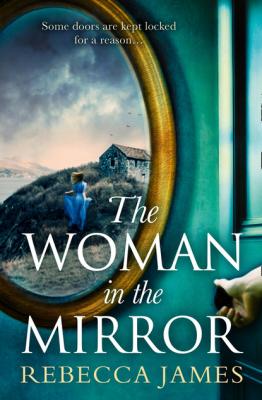

The Woman In The Mirror. Rebecca James

Читать онлайн.Название The Woman In The Mirror

Год выпуска 0

isbn 9781474073172

Автор произведения Rebecca James

Жанр Сказки

Серия HQ Fiction eBook

Издательство HarperCollins

‘I’m sorry,’ he turns to me, ‘he occasionally does this. Normally I can get him out before he does. It must be rats down there; he’s picking up a scent.’

‘Let’s follow,’ I say, thinking it rather good luck. We walk. He talks.

‘Jonathan is that breed of man who doesn’t readily admit weakness,’ the doctor says carefully, his instinct towards friendliness wishing to answer my question but his professionalism keeping him within reasonable bounds. It interests me that he refers to the captain by his name – it makes my employer seem less remote, more like an ordinary person, no one to be afraid of. ‘He comes from that sort of family,’ Henry says, ‘old English, stiff upper lip, that sort of thing. When he went off to war, there was no question of his surviving. The de Greys were – are – an institution in Polcreath; the idea of one of them falling victim to as trifling a matter as war was unthinkable. The captain wasn’t just to live: he was to triumph.’

We embark down the stairs. ‘Tipper!’ he calls. ‘Damn dog. Sorry for my language. He’s old; I shouldn’t bring him on my rounds any more.’

‘Are the captain’s injuries very bad?’

The doctor considers his reply. ‘They are as they appear,’ he says at length, as he helps me down the steps. It’s cold and dank, this lower part of Winterbourne shut off from the rest of the house so that it feels as if we are trespassing. ‘When his Hawker Hurricane went down over France, it was a miracle he was dragged out alive. Some might say a few burns and a dicky knee were a small price to pay.’

‘Is there potential for improvement?’

‘With the knee, certainly, but with injuries like this, a big part of the patient’s recovery is caught up in his outlook. Frustration doesn’t come close to describing it, particularly for a man in Jonathan’s position. He sees his war wounds as failings, where others might see them as strengths, badges of honour, however you like to describe it. Jonathan is a brave man, no doubt about it. But he isn’t the most open to accepting a doctor’s help. If he didn’t have to see me at all, I’m sure he’d be glad.’

We emerge into a fusty corridor, sooty with dust and cobwebs.

‘This must be the old servants’ quarters,’ I say out loud, and Henry nods, remembering I don’t yet know the house. From the way he stalks ahead, peering behind doors after his dog, it’s clear he’s been down here several times, probably for the same reason. I look up and see the bell box Mrs Yarrow was talking about, the one the evacuees used to play havoc with. It’s a handsome thing, its gold edges tarnished but the dozens of names beneath the chimes are visible: DINING ROOM, STUDY, LIBRARY, MASTER BEDROOM… I imagine the servants rushing along this corridor in another decade, bright with bustle. Now, it’s as quiet as a graveyard.

‘Tipper!’ Henry is shouting. ‘Get back here, you useless mutt!’

The doctor encourages me to turn back; he’ll be up with the dog soon enough. But I’m looking at that bell box, picturing the maids rushing up to the captain’s bedside. I’m picturing the woman in bed beside him.

‘Did his wife die while he was away?’ The darkness makes me bold. Here we cannot be heard, cannot be seen. Here, I can say what I like.

Henry shakes his head. ‘The captain’s crash happened in ’41. He was no good to the effort after that and came straight back to Winterbourne. She’d struggled while he was absent, of course, coping with two babies on her own. But it wasn’t until the following year that she died.’ There, he stops. He knows we have stumbled off limits.

‘I don’t mean to speak out of turn,’ I say, hoping to assure him of my loyalty. ‘It’s just I feel such affiliation with Edmund and Constance, and in turn with Winterbourne, and in turn with the captain. I care for them all.’

‘I understand. But the death of Laura de Grey isn’t a matter for discussion, here or anywhere in Polcreath. I should never have entertained it.’

Her name coats me like heat. It’s the first time I have heard it. Laura.

I have an almost overwhelming desire to say it aloud, but I don’t. Her husband would have left to fight right after their twins were born, leaving her to deal with their infancy by herself. I recall Mrs Yarrow talking about the evacuees and the bell box, about those howling hounds belonging to the man called Marlin, and how Laura was kept awake at night, exhausted and alone, prey to two screaming nurslings, growing to hate Winterbourne and its severe outlook, its arched windows and gloom-laden passages, the thrashing sea outside mirroring the thrashing in her mind, wishing fervently for her husband’s return… And when the captain did come back, had he been the same? Physically he was compromised, yes, but was he the man she’d married, in spirit, in soul, in temperament? Did he look at her in the same way; did he talk to her as he had? Laura. The mother. The wife. The powerful.

Laura.

‘I shouldn’t have raised it,’ I say. ‘I’m sorry.’

We are interrupted by a frantic bark. ‘At last!’ the doctor mutters, and I follow him down the hall and towards another set of descending steps. Just how deep does Winterbourne go? ‘I should have known he’d be here,’ says Henry, as the barking becomes a higher pitched yap, a moan, nearly, as if Tipper has hurt himself. ‘The cellar – again!’ We arrive in a small, damp room: the full stop of the house. It can’t be longer than a few metres, and the walls are exposed stone, mottled black. There are a few empty crates on their sides on the dusty ground.

‘Is he all right?’

Henry grabs the dog’s collar and attempts to soothe him, but the animal is wild. I take a step back: Tipper’s eyes are mad, his mouth pulled over his gums, his teeth bared. Saliva darts from his tongue with each expulsion. His fur stands on end, his spine arched, his tail set. He yelps then cowers, yelps then cowers.

‘Come now, boy,’ says the doctor gently, ‘it’s just a silly old door.’

I see the door he means, though I didn’t at first. It is set in the corner, lost in shadow but not quite. It is unfeasibly old-looking, and small, so small as to be uncertain if it was intended for a person to walk or crawl through. Its wood is cracked and splintered with age. In the style of the house, it wears a gothic arch, with a heavy rounded handle partway down. I try the handle but it doesn’t give.

‘Why is he afraid?’ I ask.

‘He’s an old dog full of bad habits,’ says the doctor lightly, although I can see he’s as keen to get back upstairs as I am.

‘Where does it lead?’

Henry doesn’t know. ‘I should think there’s a lot of old rubbish behind there,’ he says. ‘Tipper can smell it.’ He’s struggling to restrain the dog. ‘Let’s go.’

We head back the way we’ve come, Tipper dipping his head, his tail bowed, staying tight to his master’s heel. ‘That’s the last time I bring you with me, do you hear?’ he says gently to the hound. Before we ascend the final staircase, I look behind, wondering at this cold, abandoned netherworld, seeing that strange door, beyond which Tipper knew about something we did not.

I hear her name again.

Laura.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить