ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

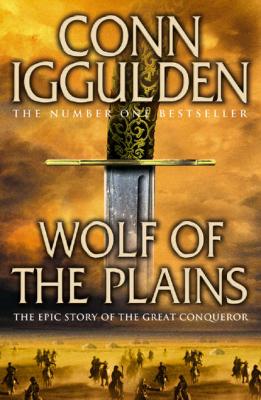

Wolf of the Plains. Conn Iggulden

Читать онлайн.Название Wolf of the Plains

Год выпуска 0

isbn 9780007285341

Автор произведения Conn Iggulden

Издательство HarperCollins

He enjoyed being away from the chatter and noise of the gers. When his father was absent, he sensed a subtle difference in the way the other men treated him, especially Eeluk. The man was humble enough when Yesugei was there to demand obedience, but when they were alone, Bekter sensed an arrogance in the bondsman that made him uncomfortable. It was nothing he could have mentioned to his father, but he walked carefully around Eeluk and kept his own counsel. He had found the best course was simply to remain silent and match the warriors at work and battle drills. There at least, he could show his skills, though it helped not to have Temujin’s eyes on the back of his neck as he drew his bow. He had felt nothing but relief when Temujin went to the Olkhun’ut. In fact, he had taken satisfaction from the hope that his brother would have a little sense beaten into him, a little respect for his elders.

Bekter remembered with pleasure how Koke had tried to bait him on his very first day. The younger boy had not been a match for Bekter’s strength or ferocity and he had knocked him down and kicked him unconscious. The Olkhun’ut had seemed shocked by the violence, as if boys did not fight in their tribe. Bekter spat at the memory of their sheep-like faces accusing him. Koke had not risked taunting him again. It had been a good lesson to give early.

Enq had thrashed him, of course, with one of the felting sticks, but Bekter had borne the blows without a single sound, and when Enq was panting and tired, he had reached out and snapped the stick in his hands, showing his strength. They had left him alone after that and Enq had known better than to work him too hard. The Olkhun’ut were as weak as Yesugei said they were, though their women were soft as white butter and stirred him as they walked by.

He thought his betrothed would surely have come into her blood by now, though the Olkhun’ut had not sent her. He remembered riding out onto the plains with her and laying her down by the bank of a stream. She had struggled a little at first when she realised what he was doing and he had been clumsy. In the end, he’d had to force her, though it was no more than he had a right to do. She should not have brushed past him in the ger if she didn’t want something to happen, he told himself, smiling at the memory. Though she had cried a little afterwards, he thought she had a different light in her eye. He felt himself growing stiff as he recalled her nakedness, and wondered again when they would send her. Her father had taken a dislike to him, but the Olkhun’ut would not dare refuse Yesugei. They could hardly give her to another man after Bekter had spilled his seed in her, he thought. Perhaps she would even be pregnant. He did not think it was possible before the moon’s blood began, but he knew there were mysteries there that he did not fully understand.

The night was growing too cold to be tormenting himself with fantasies and he knew better than to be distracted from his watch. The families of the Wolves accepted that he would lead them one day, he was almost certain, though in Yesugei’s absence they all looked to Eeluk for orders. It was he who had organised the scouts and watchers, but that was only to be expected until Bekter took a wife and killed his first man. Until that time, he would still be a boy in the eyes of seasoned warriors, as his brothers were boys to him.

In the gathering gloom, he saw a dark spot moving out on the plain below his position. Bekter rose to his feet instantly, pulling his horn free of the folds of his deel. He hesitated as he raised it to his lips, his eyes searching for more of a threat than a single rider. The height he had chosen gave him a view of a great expanse of the grassland and whoever it was seemed to be alone. Bekter frowned to himself, hoping it was not one of his idiot brothers out without telling anyone. It would not help his status in the tribe if he called the warriors from their meal without cause.

He chose to wait, watching as the tiny figure came closer. The rider was clearly in no hurry. Bekter could see the pony was walking almost aimlessly, as if the man on his back was wandering without a destination.

He frowned at that thought. There were men who claimed allegiance to no particular tribe. They drifted between the families of the plains, exchanging a day’s work for a meal or occasionally bringing goods to trade. They were not popular and there was always the danger that they would steal whatever they could lay their hands on, then disappear. Men without a tribe could not be trusted, Bekter knew. He wondered if the rider was one of those.

The sun had sunk behind the hills and the light was fading quickly. Bekter realised he should sound his horn before the stranger was lost in darkness. He raised it to his lips and hesitated. Something about the distant figure made him pause. It could not be Yesugei, surely? His father would never ride so poorly.

He had almost waited too long when he finally blew the warning note. The sound was long and mournful as it echoed across the hills. Other horns answered him from watchers around the camp and he tucked it back into his deel, satisfied. Now that the warning had been given, he could go down to see who the rider was. He mounted his mare and checked his knife and bow were within easy reach. In the silence of the evening, he could already hear answering shouts and the sound of horses as the warriors came boiling out of the gers. Bekter dug in his heels to guide his pony down the slope, wanting to get there before Eeluk and the older men. He felt a sense of ownership for the single rider. He had spotted him, after all. As he reached the flat ground and broke into a gallop, thoughts of the Olkhun’ut and his betrothed slipped away from his mind and his heart began to beat faster. The evening wind was cool and he hungered to show the other men that he could lead them.

The Wolves rode hard out of the encampment, Eeluk at their head. In the last moments of light, they saw Bekter kick his mount into a run and went after him, not yet seeing his reason for raising the alarm.

Eeluk sent a dozen riders left and right to skirt the camp, looking for an attack from another direction. It would not do to leave the gers defenceless while they went after a feint or a diversion. Their enemies were devious enough to draw the watchers away and then attack, and the last moments of light were perfect to cause confusion. It felt strange for Eeluk to be riding without Yesugei on his left, but Eeluk found he was enjoying the way the other men looked to him to lead them. He snapped orders and the arban formed around him with Eeluk on the point, racing after Bekter.

Another blast from a horn came from just ahead and Eeluk narrowed his eyes, straining to see. He was almost blind in the gloom and to gallop was to risk his mare and his life, but he kicked his horse on recklessly, knowing Bekter would not have blown again unless the attack was real. Eeluk snatched at his bow and placed an arrow on the string by feel, as he had done a thousand times before. The men around him did the same. Whoever had dared to attack the Wolves would be met with a storm of whining shafts before they came much closer. They rode in grim silence, high on the stirrups, balancing perfectly against the rise and fall of their ponies. Eeluk pulled back his lips in the wind, feeling the thrill of the attack. Let them hear the hooves thundering towards them, he thought. Let them fear retribution.

In the dark, the riding warriors almost collided with two ponies standing alone on the open ground. Eeluk came close to loosing his arrow, but he heard Bekter shouting and, with an effort, he lowered himself into the saddle and eased his string. The battle blood was still strong in him and he felt a sudden fury that Yesugei’s son had brought them out for nothing. Dropping his bow over the saddle horn, Eeluk leapt lightly to the ground and drew his sword. The darkness was on them and he did not yet know what was happening.

‘Eeluk! Help me with him,’ Bekter said, his voice high and strained.

Eeluk found the boy holding the slumped figure of Yesugei on the ground. Eeluk felt his heart thump painfully as the last traces of battle rage slid away from him and he knelt by the pair of them.

‘Is he injured?’ Eeluk said, reaching out to his khan. He could hardly see anything, but he rubbed his fingers and thumb together and sniffed at them. Yesugei’s stomach was tightly bound, but blood had soaked through.

‘He fell, Eeluk. He fell into my arms,’ Bekter said, close to panic. ‘I could not hold him.’