ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

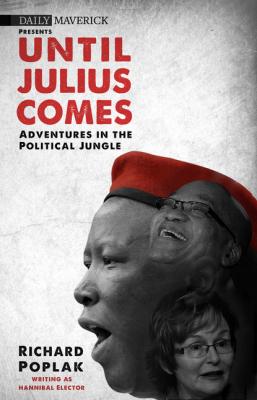

Until Julius Comes. Richard Poplak

Читать онлайн.Название Until Julius Comes

Год выпуска 0

isbn 9780624070108

Автор произведения Richard Poplak

Издательство Ingram

The ANC’s campaign party truck was parked on President Street, under the gaze of the library building’s friezes depicting Goethe, Cervantes, Shakespeare, Dante and friends. These concrete literary giants, forming a row on the northern wall of the library’s edifice under which the party truck was installed, seemed to regard what was happening below with recognition, as if they were thinking, ‘Yup, there was lots of this crap in my day, too.’

On my way to a prime viewing spot, I encountered the provincial treasurer of the students’ union, and we fought through the crowd together. He wore boxing gloves and a slingshot around his neck. I told him that he looked ready.

‘We are ready,’ he said. ‘We are ready.’

Jessie Duarte, the ANC’s Deputy Secretary General, provided the warm-up act, if that’s the proper way to describe it. She addressed, as everyone seems to these days, ‘the youth’.

‘Helen Zille’s husband is a lecturer at UCT,’ she reminded the faithful. ‘But he doesn’t want you there. The ANC is saying, “Not on our watch!”’

The crowd had filled out with a representative ensemble of those unable to find work in this country: old women, and young men in their prime. ‘Today,’ Duarte promised them, ‘we are not going to waste this day. We heard in the news that the visitors are not ready. If they come next week, next year, we will be ready. Now, what we are going to do is political education.’

Which meant handing out pamphlets and dog-eared copies of the manifesto to taxi drivers and passers-by.

Duarte went on to blame the current anti-march non-rally rally on ‘Stan Greenman or something’, a presumed reference to the American pollster Stan Greenberg, who has advised everyone from Bill Clinton, evil monster vegetable maker Monsanto and, wait for it, the ANC itself. He ditched the ruling party in 1999 because Thabo Mbeki’s stance on Aids horrified him, and in 2013 agreed to provide his services to the DA, in no small part because of a long-standing friendship with the party’s national chairperson, Wilmot James. Greenberg has described his role as that of ‘an outside adviser to the existing local DA polling operation’, and he’s been bullish on the DA’s polling numbers. But he would be.

The DepSecGen, however, saw a conspiracy: ‘[Greenberg] says, “Go to the ANC, because they will react violently.” But this is not America. This is South Africa,’ implying that the incoming DA marchers, should they ever arrive, would be handed cups of Oros and reams of ANC literature, and not be provoked into a street war.

Later, I got talking with two younger comrades, one wearing a black beret and a T-shirt emblazoned with an image of an AK-47. Mpumi told me that he and his comrades would have stopped the march if it had occurred. ‘This is our house,’ he said, pointing to the HQ’s concrete facade. ‘This is our heart. The correct place to go with their grievances is the Union Buildings. Go to Pretoria. Don’t come here.’

I asked him about the DA’s septimana horribilis – the brief, disastrous Mamphela marriage –presumably all the fault of Stan Greenberg. ‘It was empty, there’s nothing to talk about. It’s a sign of desperation to get black voters. It’s a rent-a-black mentality. They want a BEE president. But, let’s be honest, Mamphela Ramphele is not really that black.’

By now, the rotund Secretary General, Gwede Mantashe, had been hoisted onto the party truck. He held aloft the storied manifesto. He addressed ‘the youth’.

‘There has been a divorce in the DA,’ said Mantashe. ‘Because the divorce was complicated, they did not arrive. They wanted to storm the Bastille. Very ambitious. Very ambitious.’

Not really. The DA was happy to gamble with the safety of their supporters; so too was the ANC. It’s just people, and there are lots where they came from. But what would have been welcome was if the official opposition had pulled back from all the stunt work and started to campaign for the 2014 general elections like a sophisticated political party, and not like COPE’s nursery-school wing. The DA didn’t need provocative marches. They just needed a week that didn’t make them look like schmucks.

THE METAPHORAI

12 FEBRUARY 2014, JOHANNESBURG CBD

In which the Democratic Alliance marches to Luthuli House, to present a demand, wrapped inside a proposal, for 6 million ‘real jobs’.

‘In modern Athens,’ the philosopher Michel de Certeau once noted, ‘the vehicles of mass transportation are called metaphorai. To go to work or to come home, one takes a “metaphor”.’

One week after the ANC’s non-march, anti-rally rally, Johannesburg was, as usual, jammed with metaphors – in this case, the buses that brought in DA supporters and ANC supporters, who gathered on either side of the central business district.

‘Viva Helen Zille viva,’ yelled one half of the city. ‘Viva President Zuma viva,’ yelled the other.

The meaning of the humming metaphors that lined Miriam Makeba was easy to decipher: in a divided city, which was built to maintain divisions, the buses were intended to make those divisions plain. The DA, led by Helen Zille, were here to deliver a jobs proposal to the ANC, who were encamped to protect the integrity of the revolutionary house from those who hoped to defile its honour.

Before the first Molotov cocktail had been thrown, before the first rubber bullet had been fired, I stood outside Luthuli House and spoke with a Department of Community and Safety spokesperson named Obed T.I. Sibasi. He assured me that the morning would unfold without trouble. We were alongside in a circle of dancing ANC supporters, and Sibasi was explaining how it was his department’s responsibility to protect citizens, not encourage their shitty behaviour.

‘That is why we will ensure that the DA will avoid this area’ – he was pointing to Luthuli House’s entrance – ‘for the sake of the peace. That is why we say there will be no problems.’

It was difficult to know whether Sibasi and I inhabited the same reality because, from my vantage point, problems looked both imminent and certain. The ANC contingent, now a couple of thousand strong, were armed with struggle songs, cattle crops, sticks, bricks, bats, flags, freezies, berets and T-shirts. They were, to my eyes, a fully operational street army. To Sibasi, however, they represented a slight traffic headache.

‘Will the DA make it to Luthuli House to deliver their jobs thing?’ I asked.

‘We are not sure of the outcome,’ Sibasi told me. ‘But that is not our business. We are concerned with public safety.’

With that in mind, I strolled along Marshall Street towards the DA encampment, which had been set up at the Westgate Transport Hub at Miriam Makeba and Anderson. A city sliced in half – yellow and green hither, blue and white thon. Getting my white ass into the DA assembly area was no easy task – first, I was frisked by an enormous nightclub bouncer wearing a black dinner jacket, dark jeans and a neon safety vest, and then I was frisked by another. The DA’s security contingent seemed recruited from nearby nightclubs, their expertise better suited to selling cocaine and punching drunk people in the face than managing a political rally.

Inside, the DA supporters were armed with T-shirts, berets, white-dude ponytails, fat hippies, flags, and signs that read ‘6 million REAL jobs now’. The DA’s Gauteng leader, John Moodey, dressed like a Sylvester Stallone character in a black beret, aviator shades and a flak jacket, warned those who had brought children to stay behind. ‘We will have no children on the march,’ he said. ‘We’re marching for their future.’ Dead babies, after all, make for