ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

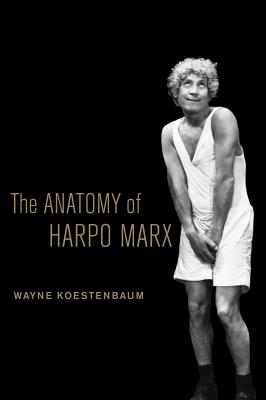

The Anatomy of Harpo Marx. Wayne Koestenbaum

Читать онлайн.Название The Anatomy of Harpo Marx

Год выпуска 0

isbn 9780520951983

Автор произведения Wayne Koestenbaum

Жанр Кинематограф, театр

Издательство Ingram

Harpo steals the basso’s blazer and puts it on Chico. Harpo steals to please his family. Like Oliver Twist under Fagin’s charge, Harpo presents theft’s gleaning to an underworld boss—not to garner acclaim, but to remain securely in the position of tolerated little brother. Brotherliness has a queer energy that Walt Whitman called “adhesiveness”: the democratic desire to attach.

IMMUNITY TO COQUETRY Harpo may chase women, but he foils their advances: heterosexuality, for Harpo, doesn’t compute. And yet Kay Francis, the film’s vamp (soon she’ll star in George Cukor’s Girls about Town and Ernst Lubitsch’s Trouble in Paradise), tries to snare Harpo’s libido. They seem an unlikely match: she’s tall and not Jewish. Flirtatiously, she drops a handkerchief, but he mistakes love-gift for plunder, which he pockets. “Did you see a handkerchief?” she asks. He shakes his head “no” and mimics coquetry by acting femme, while his teeth extract a scarf from her bodice. Earlier, he played this trick on the detective, but Kay’s hankie is longer than the Law’s, and comes from a more intimate hiding place. Harpo mocks private property, puts his mouth to improper use, and interrupts other people’s insincerity. His mouth considers Kay’s hankie an abstract prize, which he hides in his pocket, an almost anatomical safe-deposit box.

WHY HARPO LOOKS DIRECTLY AT THE CAMERA Later, he will learn not to look at the camera. But now, in this primal film, he commits the sin of acknowledging our presence. Mincing, hand on hip, like Mae West, he looks directly at us. His lapse allows me to argue: Harpo, expressing a naked need-for-audience, smashes the diegesis (the technical word for everything that takes place within a film’s fictional world). And by smashing the diegesis, Harpo carves a covert for reverie and for threshold experiences beyond conventional moral accounting systems, including regimes that divide useful and useless acts, and regimes that compel us to choose sociability over introspection.

His horn, colliding with the shutting elevator door, squawks, and he steps backward, arrested, unsmiling, slack-faced. He has failed to prime his features with a signifying expression. Blankness propels him toward music-making; going blank, he relinquishes interaction. Harpo may wish to attach himself to others—especially brothers—but because he lacks speech, he will only thrive when solitary. His contemplative episodes seem like locales rather than merely moods. Consider Harpo a homesteader. Not necessarily a Zionist. (However, at his death, he bequeathed his harp to Israel. I assume that Israel accepted the gift.) Onscreen, he seems a man concerned with escape and territory; his musical solos represent benign, nonviolent flight from the demands of the Other. Harpo, despite clannish chumminess, thrives when abandoned, and when he interacts with his instrument. When I was young, I loved Charlie Chaplin because, clumsy and pallid, he invited us to watch him sulk. Harpo never sulks, and rarely feels sorry for himself, and yet he leans toward emptiness, as if hunting for an echo.

II

HARP AS HOMELAND Seriousness descends. (A rule of Harpo Existence: you can’t make music while kidding around.) Stranded, he has no companion, only a clarinet: he can shove no one else’s body into his transformation factory. He empties himself of alacrity; he needs to purge himself before he dares to perform. His grave face illustrates the pleasure of evacuated meaning. When he plays clarinet, his right cheek expands, but not the left: asymmetrical sign of effortful, onanistic pathos.

Clarinet is just a warm-up; his real instrument is the harp. His harp adventures never change, though their meanings deepen with reiteration: repetition allows us to discover what was immanent in an experience the first go-round. How can we understand Harpo’s harp playing, unless we visit every instance?

In this inaugural experiment, Harpo prepares for solo by posing as bogeyman—looking at the viewer through harp strings, and making a scary face, Hollywood’s idea of a savage. Change of mood: serious, he sits down at the harp, an instrument not meant for men. Harpo’s seriousness butches up the suspect effort. Digital aplomb confirms sexual expertise: this guy knows how to use his fingers. Comedy dies: nap time begins. We can turn away from interaction, moneymaking, cadging, aggression, and garrulity; we can focus, instead, on Harpo’s lushly arpeggiated “soul”—the realm of Jewish feeling, Harpo’s version of singing the blues, a wail with a historical core. The solo’s spiritually assiduous style, a Covenant, is cut off from hijinks. The Marx Brothers never rest; arrivistes, they gate-crash other people’s estates and institutions. Only Harpo’s harp episodes broach the question of homeland. Finally, he gives up hectic transit and failed encounter; finally, he pursues an unbroken, self-generated line of thought.

A medium shot narrows to a close-up, framing Harpo’s face; the viewer presumably wants to spy on Harpo’s private musings, his necromancy—a spell aimed at himself, not at others. Like Garbo, Harpo at his harp is starry, alienated, commodifiable, contained, worth studying and collecting. We see Harpo’s nose in profile. We see how a Jew behaves in secret—an Orpheus with an overlarge, stolen lyre. Harpo, the Jewish fool, plays the instrument that signified, for the British romantic poets, and for anyone influenced by them, the strings of the imagination. In Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s “The Eolian Harp,” nature is a harp, waiting to be plucked by the “intellectual breeze.” Harpo has a lot of responsibility: the fate of Western lyricism rests in his capable, gummy hands.

“WHY BOTHER?” Harpo goes down on all fours, like a baby or a dog, and crawls under Kay’s bed. He loves nooks. He can play marauder without posing a sexual threat. He also possesses the virtue of being empty. He escapes sexual grids; he likes sequestration (pockets, hideaways); he tends toward the animalistic and the puerile; and he prefers to rid actions and objects of their meanings, rather than pile up new meanings.

Leaving his under-the-bed hiding place, Harpo swims like a seal, a watery jet squirting out his mouth: arms make undinal motions, and he wiggles across the floor. Toward humankind he says, “Why bother?” He becomes animal not merely to transgress but to unwind.

JACK-IN-THE-BOX: SUDDEN MANIFESTATION Harpo knocks and enters Margaret Dumont’s room. Margaret Dumont—where do I begin?—is the dowager, the goalpost, the butt of jokes, the consoling maternal presence, the pillar, the wailing wall, the frame, the woman with kind eyes and haughty voice, the woman who bars the brothers from high society but also ushers them into it. Toward Margaret, the cure-all and guardian, the ripe-toned enunciator with a heart of schmaltz, Harpo carries a pitcher of ice water: erotic indifference? Margaret tells him to put the pitcher on the bureau. Instead, Harpo goes to her bed, lies down, and pats the mattress as invitation. When she indignantly refuses, he waves good-bye and exits.

Knock knock. Margaret says, “Come in.” It’s Harpo again—programmed, with a mechanical, tick-tock rhythm, to pop into framed spaces. But then, discovering his mistake (wrong room!), he flees.

Harpo, jack-in-the-box, enacts a rhythm of sudden emergence: I’m-here, quickly followed by I’m-not-here. Harpo is happiest when he first appears. Soon afterward, identity falls prey to dilution. The blitzkrieg instant of arrival finds him most “Harpo.”

GROUCHO’S THIRD-PERSON REFERENCES TO HARPO Groucho says that he doesn’t want to see that “red-headed fellow” running around the lobby. (The film is black-and-white; we’ll take Harpo’s hair color on faith.) Groucho, rarely speaking to him, refers to him in the third person, and holds him within the pincers of adjectives and pejoratives. Later I will describe this effect as the “coziness of interpellation.” It is cozy to be invoked (“that red-headed fellow”) by your brother, even if the reference is negative. It is cozy to be named, and thus summoned into existence.

PLEASURE OF THE INSTANT BEFORE CATEGORIES CLICK INTO PLACE Harpo has little sense of good or evil; freedom from categories accords him cognitive cleanliness. When he does a good deed—he retrieves Margaret