ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

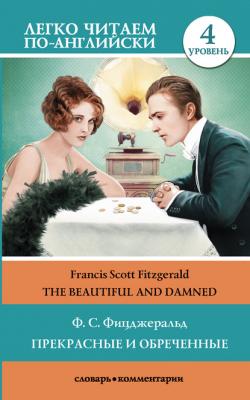

The Beautiful and Damned / Прекрасные и обреченные. Уровень 4. Фрэнсис Скотт Фицджеральд

Читать онлайн.Название The Beautiful and Damned / Прекрасные и обреченные. Уровень 4

Год выпуска 1922

isbn 978-5-17-120007-7

Автор произведения Фрэнсис Скотт Фицджеральд

Жанр Зарубежная классика

Серия Легко читаем по-английски

Издательство Издательство АСТ

This was his healthy state and it made him cheerful, pleasant, and very attractive to intelligent men and to all women. In this state he considered that he would one day accomplish some quiet subtle thing. Until the time came for this he would be Anthony Patch.

A Worthy Man And His Gifted Son

Anthony was the grandson of Adam J. Patch. Adam J. Patch, more familiarly known as “Cross Patch[3],” left his father’s farm in Tarrytown[4] early in sixty-one to join a New York cavalry regiment. He came home from the war a major, walked to Wall Street, and he gathered for himself some seventy-five million dollars.

This occupied his energies until he was fifty-seven years old. Then, after a severe attack of sclerosis, he decided to consecrate the remainder of his life to the moral regeneration of the world. He became a reformer among reformers. From an armchair in the office of his Tarrytown estate he directed against the enormous hypothetical enemy, unrighteousness.

Early in his career Adam Patch had married an anemic lady of thirty, Alicia Withers[5], who brought him one hundred thousand dollars. Immediately she had borne him a son. The boy, Adam Ulysses Patch, became an inveterate joiner of clubs, and at the age of twenty-six he began his memoirs under the title “New York Society as I Have Seen It.”

This man married at twenty-two. His wife was Henrietta Lebrune[6], and the single child of the union was, at the request of his grandfather, christened Anthony Comstock Patch. Young Anthony had one picture of his father and mother together. It showed a dandy of the nineties, standing beside a tall dark lady with a muff. Between them was a little boy with long brown curls, dressed in a velvet suit. This was Anthony at five, the year of his mother’s death.

His mother was a lady who sang, sang, sang, in the music room of their house on Washington Square – sometimes with guests scattered all about her, and often she sang to Anthony alone, in Italian or French or in a strange and terrible dialect.

After Henrietta Lebrune Patch had “joined another choir,” as her widower remarked, father and son lived up at grandfather’s in Tarrytown. Ulysses came daily to Anthony’s nursery and was continually promising Anthony hunting trips and fishing trips and excursions to Atlantic City, “oh, some time soon now”; but none of them ever materialized. One trip they took; when Anthony was eleven they went abroad, to England and Switzerland, and there in the best hotel in

Lucerne his father died. Anthony was brought back to America, and a vague melancholy stayed beside him through the rest of his life.

Past And Person Of The Hero

At eleven he knew a horror of death. Within six years his parents had died and his grandmother had faded off almost imperceptibly. So to Anthony life was a struggle against death, that waited at every corner. He formed the habit of reading in bed – it soothed him. He read until he was tired and often fell asleep with the lights still on.

His favorite diversion until he was fourteen was his stamp collection; his grandfather considered fatuously that it was teaching him geography. His stamps were his greatest happiness; they devoured his money.

At sixteen he became an inarticulate boy. His private tutor persuaded to go to Harvard.

There he lived for a while alone – a slim dark boy of medium height with a shy sensitive mouth. He laid the foundations for a library by purchasing from a wandering bibliophile some books, finding later that he had paid too much. He became an exquisite dandy, bought a pathetic collection of silk pajamas, brocaded dressing-gowns, and neckties too flamboyant to wear. In this he could parade before a mirror in his room.

Curiously enough he found that he was looked upon[7]as a rather romantic figure, a scholar, a recluse, an erudite. This amused him but secretly pleased him. In 1909, when he graduated, he was only twenty years old.

Then abroad again – to Rome this time, architecture and painting. He wrote some ghastly Italian sonnets.

He returned to America in 1912 because of his grandfather’s sudden illness, and decided to put off the idea of living permanently abroad. He took an apartment on Fifty-second Street and settled down.

In 1913 Anthony Patch’s shoulders had widened and his brunette face had lost the frightened look. His friends declared that they had never seen his hair rumpled. His nose was too sharp; his mouth was a mirror of mood, but his blue eyes were charming. Moreover, he was very clean, in appearance and in reality, with that especial cleanness borrowed from beauty.

The Work

His apartment was kept clean by an English servant with the appropriate name of Bounds. From eight until eleven in the morning he was entirely Anthony’s. He arrived with the mail and cooked breakfast. At nine-thirty he pulled the edge of Anthony’s blanket; then he served breakfast on a card-table in the front room, made the bed and, after asking with some hostility if there was anything else, went away.

In the mornings, at least once a week, Anthony went to see his broker. His income was slightly under seven thousand a year, he inherited money from his mother. His grandfather judged that this sum was sufficient for young Anthony’s needs. Every Christmas he sent him a five-hundred-dollar bond, which Anthony usually sold.

Anthony always enjoyed the visits to his broker. The big trust company building linked him to the great fortunes. From the hurried men he derived the sense of safety.

Some golden day, of course, Anthony would have many millions. Let’s go back to the conversation with his grandfather immediately upon his return from Rome.

He had hoped to find his grandfather dead, but had learned by telephoning that Adam Patch was comparatively well again – the next day he had concealed his disappointment and gone out to Tarrytown.

Anthony was late and the venerable philanthropist was awaiting him in a parlor, where he was glancing through the morning papers for the second time. His secretary ushered Anthony into the room.

They shook hands gravely.

“I’m glad to hear you’re better,” Anthony said.

The senior Patch pulled out his watch.

“Train late?” he asked mildly. And then after a long sigh, “Sit down.”

Anthony felt that he was expected to outline his intentions. He wished that the secretary would have tact enough to leave the room.

“Now you ought to do something,” said his grandfather softly, “accomplish something.”

Anthony made a suggestion:

“I thought – it seemed to me that perhaps I’m best qualified to write – “

Adam Patch winced, visualizing a family poet with a long hair and three mistresses.

“ – history,” finished Anthony.

“History? History of what? The Civil War? The Revolution?”

“Why – no, sir. A history of the Middle Ages.”

“Middle Ages? Why not your own country? Something you know about?”

“Well, you see I’ve lived so much abroad – “

“Why you should write about the Middle Ages, I don’t know. Dark Ages, we call them. Nobody knows what happened, and nobody cares, except that they’re over now. Do you think you’ll be able to do any work in New York – or do you really intend to work at all?”

This last with soft, almost imperceptible, cynicism.

“Why, yes, I do, sir.”

The conversation came toward a rather abrupt conclusion, when Anthony rose, looked at his watch, and remarked that he had an engagement with his broker that afternoon. He had intended to stay a few days with his grandfather, but he was tired and irritated. He will come again in a few days.

Afternoon

It

Cross Patch – Сердитый Пэтч

Tarrytown – Тэрритаун

Alicia Withers – Алисия Уитерс

Henrietta Lebrune – Генриетта Лебрюн

he was looked upon – его почитали