ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

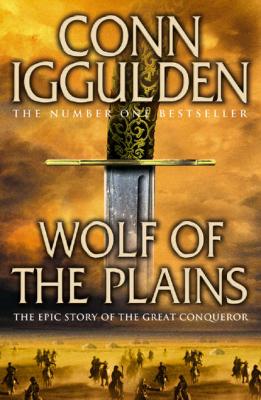

Wolf of the Plains. Conn Iggulden

Читать онлайн.Название Wolf of the Plains

Год выпуска 0

isbn 9780007285341

Автор произведения Conn Iggulden

Издательство HarperCollins

Temujin watched as Kachiun drew himself up into a crouch on the very edge of the nest, seemingly oblivious to the precarious position. Kachiun reached out a hand, but Temujin snapped a warning. ‘The clouds are too close for us to get down now,’ he said. ‘Leave them in the nest and we can take them in the morning.’

As he spoke, a rumble of thunder growled across the plains and both boys looked towards the source. The sun was still bright over them, but in the distance they could see rain sheeting down in twisting dark threads, the shadow racing towards the red hill. At that height, it was a scene to inspire awe as well as fear.

They shared a glance and Kachiun nodded, dropping back from the nest edge to the one below.

‘We’ll starve,’ he said, putting his sore finger in his mouth and sucking at the crust of dried blood.

Temujin nodded, resigned. ‘Better that than falling,’ he said. ‘The rain is nearly here and I want to find a place where I can sleep without dropping off. It will be a miserable night.’

‘Not for me,’ Kachiun said, softly. ‘I have looked into the eyes of an eagle.’

With affection, Temujin cuffed the little boy, helping him traverse the ridge to where they could climb further up. A cleft between two slopes beckoned. They could wedge themselves in as far as possible and rest at last.

‘Bekter will be furious,’ Kachiun said, enjoying the idea.

Temujin helped him up into the cleft and watched him wriggle his way in deeper, disturbing a pair of tiny lizards. One of them ran to the edge and leapt in panic with its legs outstretched, falling for a long time. There was barely room for both boys, but at least they were out of the wind. It would be uncomfortable and frightening after dark and Temujin knew he would be lucky to sleep at all.

‘Bekter chose the easy way up,’ he said, taking Kachiun’s hand and pulling himself in.

The storm battered the red hill for all the hours of darkness, clearing only as dawn came. The sun shone strongly once more from an empty sky, drying the sons of Yesugei as they emerged from their cracks and hiding places. All four had been caught too high to dare a descent. They had spent the night in shivering wet misery; drowsing, then jerking awake with dreams of falling. As the dawn light reached the twin peaks of the red hill, they were yawning and stiff, with dark circles under their eyes.

Temujin and Kachiun had suffered less than the other pair because of what they had found. As soon as there was light enough to see, Temujin began to scramble out of the cleft to collect the first of the young eagles. He almost lost his grip when a dark shape swept in from the west, an adult eagle that seemed as large as he was.

The bird was not happy to find two trespassers so close to its young. Temujin knew the females were larger than the males and he assumed the creature had to be the mother, as it screamed and raged at them. The chicks went unfed as the great bird took off again and again to float on the wind and look into the rock cleft that sheltered the two boys. It was terrifying and wondrous to be so high and stare into the black eyes of the bird, hanging unsupported on outstretched wings. Its claws opened and clutched convulsively, as if it imagined tearing into their flesh. Kachiun shuddered at the sight, lost in awe and fear that the huge bird would suddenly spear in at them, winkling them out as it might have done with a marmot in its hole. They had no more than Temujin’s pitiful little knife to defend themselves against a hunter that could break the back of a dog with a single heavy strike.

Temujin watched the brown-gold head turn back and forth in agitation. He guessed the bird could remain there all day and he did not enjoy the thought of being exposed on the ledge below the nest. One blow from a claw there and he would be torn loose. He tried to remember anything he had ever heard about the wild birds. Could he shout to frighten the mother away? He considered it, but he did not want to summon Bekter and Khasar up to the lonely peak, not until he had the chicks wrapped in cloth and close to his chest.

At his shoulder, Kachiun clung to the sloping red rock in the cleft. Temujin saw he had prised out a loose stone and was weighing it in his hand.

‘Can you hit it?’ Temujin asked.

Kachiun only shrugged. ‘Maybe. I’d have to be lucky to knock it down and this is the only one I could find.’

Temujin cursed under his breath. The adult eagle had disappeared for a time, but the birds were skilled hunters and he was not tempted to be lured out of his safe haven. He blew air out of his mouth in frustration. He was starving, with a difficult climb down ahead of him. He and Kachiun deserved better than to leave empty-handed.

He remembered Bekter’s bow, far below with Temuge and the ponies, and cursed himself for not having thought to bring it. Not that Bekter would have let him lay a hand on the double-curved weapon. His elder brother was as pompous about that as he was about all the trappings of a warrior.

‘You take the stone,’ Kachiun said. ‘I’ll get back up to the nest, and if she comes, you can knock her away.’

Temujin frowned. It was a reasonable plan. He was an excellent shot and Kachiun was the better climber. The only problem was that it would be Kachiun who had taken the birds, not him. It was a subtle thing, perhaps, but he wanted no other claim on them before his own.

‘You take the stone. I’ll get the chicks,’ he replied.

Kachiun turned his dark eyes on his older brother, seeming to read his thoughts. He shrugged. ‘All right. Have you cloth to bind them?’

Temujin used his knife to remove strips from the edge of his tunic. The garment was ruined, but the birds were a far greater prize and worth the loss. He wrapped a length around each palm to have them ready, then craned out of the cleft, searching for a moving shadow, or a speck circling above. The bird had looked into his eyes and known what he was trying to do, he was certain. He had seen intelligence there, as much as any dog or hawk, perhaps more.

He felt his stiff muscles twinge as he climbed out into the sunlight. Once more he could hear thin screeching from the nest, the chicks desperate for food after a night alone. Perhaps they too had suffered without their mother’s warm body to protect them from the storm. Temujin worried that he could hear only one call and that the other might have perished. He glanced behind him in case the adult eagle was soaring in to hammer him against the rock. There was nothing there and he pulled himself onto the high ledge, dragging up his legs until he crouched as Kachiun had the previous evening.

The nest was deep in a hollow, wide and steep-sided, so that the active young birds could not clamber out and fall before they could fly. As they caught sight of his face, both of the scrawny young eagles scuttled away from him, wagging their featherless wings in panic and cawing for help. Once more, he scanned the blue sky and said a quick prayer to the sky father to keep him safe. He eased forward, his right knee pressing into the damp thatch and old feathers. Small bones crunched under his weight and he smelled a nauseating gust from ancient prey.

One of the birds cowered from his reaching fingers, but the other tried to bite him with its beak, raking his hand with talons. The needle claws were too small to do more than lightly score his skin and he ignored the sting as he held the bird up to his face and watched as it writhed.

‘My father will hunt for twenty years with you,’ he murmured, freeing a strip from one hand and trussing the bird by wing and leg. The second had almost climbed out of the nest in panic and Temujin was forced to drag it back by one yellow claw, causing it to wail and struggle. He saw that the young feathers had a tinge of red amidst the gold.

‘I would call you the red bird, if you were mine,’ he