ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

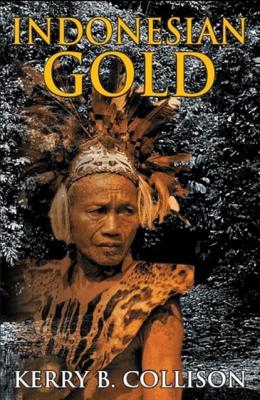

Indonesian Gold. Kerry B Collison

Читать онлайн.Название Indonesian Gold

Год выпуска 0

isbn 9781877006098

Автор произведения Kerry B Collison

Жанр Контркультура

Издательство Ingram

Bloody confrontations, hidden from the International and domestic Press through severe censorship and well-rehearsed, intimidation tactics, resulted in the Javanese-dominated military rethinking its strategies in support of transmigration in the Kalimantan provinces. Department of Defense signaled that Suharto Family interests, and those of their close associates, were to be protected at all costs. Additional troops were sent to areas where vested interest groups were in open conflict with the traditional landowners, their orders to deal swiftly and firmly with the local inhabitants.

Jonathan had witnessed evidence of the brutal RPKAD’s Special Forces in action. Word had spread through the upper Mahakam reaches that an isolated village had been razed to the ground by army elements. When he arrived at the scene, Jonathan no longer harbored any doubts that the Dayak peoples were not only in grave danger of losing their land and culture to the Javanese, but their lives as well. Amongst the still-smoldering Longhouse embers he counted more than two hundred bodies, the majority belonging to children who had obeyed their parents pleas to remain hidden inside, when the soldiers came. The RPKAD Special Forces had surrounded the raised village in crescent formation and opened fire with their automatic weapons, their bullets easily ripping through the timber-clad dwellings, killing or wounding all within. Then they torched the dry, wooden structure, the cries of their victims ignored as thatched roofs ignited spontaneously under intense heat then imploded, destroying the entire complex within minutes.

****

Throughout the following two decades Jonathan Dau conducted his own, secret war against the Javanese. He never involved others in his deadly game; neither did he reveal the real purpose of the frequent excursions that took him away from the village, often for days at a time. Jonathan was cautiously selective in his targets, killing soldiers who had strayed or become lost in the jungle. His actions were entirely covert in nature and, although he enjoyed limited success, the weight of numbers and the constant threat of discovery, finally convinced him to cease what had become a futile action. Although the government’s repressive actions continued to fuel anti-Javanese sentiment and calls for a cessation to the transmigration process, the flood continued. Jonathan sadly accepted that the Dayak people would remain subjects of their new colonial masters, the Javanese, but he still prayed that the time would come when Borneo would be returned to its original inhabitants, and the Moslems all sent home.

This was to be Jonathan Dau’s impossible dream.

The chief understood that the main impediment towards building a Dayak nation was that the Kalimantan indigenes had never been unified. Borneo’s indigenous peoples were comprised of scores of tribes, whose varied cultures and dialects had placed them poles apart, some developing from a highly stratified society with classes of aristocrats, freemen and slaves, whilst others, such as the northern Ibans, enjoyed a more egalitarian society.

Political lines now divided the great island, with Malaysia and Brunei to the north, and Indonesian-held Kalimantan to the south. Jonathan accepted that in order for the Penehing-Dayak to survive they would have to be guaranteed their own land, the question of how to achieve this aim, forever foremost in his mind. His people were but few in number and, alone, armed but with the most primitive of weapons, the possibility of a successful military confrontation never entered his mind. A pragmatist, Jonathan believed that only with great wealth could the Penehing-Dayaks’ future be secured, his conundrum, the improbability of such a dream coming to fruition. He had thought of seeking outside help to have their lands declared part of some world heritage trust, abandoning the idea when he discovered that this might very well deliver his people even sooner into Jakarta’s brutal hands. Then he embarked on a mission to have the entire area given special status, similar to that of Jogyakarta and Greater, Metropolitan Jakarta, but without central government support, this too failed. When the entire island was divided into concession areas covering minerals, oil and gas, Jonathan accepted that even the great wealth that lay below the surface would never be theirs. Now, approaching his fiftieth year, Jonathan had not mellowed, the strength of his convictions still evident in his dealings with government officials – most of whom being Javanese, or their local lackeys.

When Jonathan was elected village head, out of respect, none of his fellow villagers had challenged Jonathan’s right to lead. Out of bloody-mindedness, the East Kalimantan Governor had issued instructions for the military to identify pro-Jakarta candidates from within the local, river communities to run against the powerful spiritualist, but these efforts failed, causing an embarrassing retreat by the Javanese-appointed official.

Jonathan Dau continued to dedicate much of his time to the welfare of the Penehing people, counseling, administering cures and complying with the many, bureaucratic requests that flowed unceasingly from the Governor’s office in Samarinda. He still ventured out into the relatively unknown forests, sometimes spending days alone on the slopes of Bukit Batubrok meditating, occasionally climbing the two-thousand-meter plateau in search of the evasive plants needed for his medicinal potions. On occasion, Jonathan would take one of the village children with him, teaching the child some of the rudiments of jungle lore. The Longhouse children competed for this privilege, their parents delighted to surrender their sons to his care, for their chief had no male heir of his own. And, the possibility that their child might be the one chosen to succeed Jonathan Dau was not lost on their number. Jonathan’s wife had never fully recovered from her debilitating liver disease, surrendering to her condition, finally, when their daughter, Angela, was barely three. Jonathan did not seek another mate – such was his sense of loss. Now, he was to be alone, again. Jonathan’s daughter, Angela, was to leave to attend the Institute of Technology in Bandung.

As the day for departure neared Jonathan became heavy of heart, the impending void her absence would undoubtedly create sent him aimlessly into the fields where village women bent tirelessly, preparing the ladang for planting, their pre-school age children playing in close proximity. There, he had observed a small girl wander off unnoticed, and had retrieved the child, returning her to a grateful mother before strolling back through the naturally protected river island, and the Longhouse. It was time to take his daughter, Angela, up into the mountains.

As Jonathan Dau approached his village, he passed between guardian figures strategically placed along all paths leading to the Longhouse, to deflect evil spirits that might bring sickness to the isolated community. These sentinels took the form of both human and animal shapes, many carved deliberately displaying grotesque eyes and teeth, to intimidate intruders, and repel malevolent spirits. In this land overlooked by modern civilizations, Gods and spirits continued to play important roles in Dayak societies – the rivers and forests revered as hosts to these.

Gargoyle-like images stared down from the thatched roof as Jonathan climbed the steps leading up to the timber structure, a communal village raised three meters above the ground and more than a hundred and fifty meters in length, held together by massive, ornately carved, wooden beams. The elongated building housed more than a hundred families, each living in their own, separate apartment, joined to their neighbors’ by a central, wooden corridor, which served as the village ‘street’. Jonathan’s family quarters, and unofficial office, lay centered amongst this maze adjacent to the community meeting room. The traditional ‘gallery’ that once housed the most sacred of artifacts and enemy skulls, relics of another time, lay discreetly hidden from any visitor’s view.

Jonathan made his way through the Longhouse, stopping briefly to converse with other men, most preoccupied with their own chores, whilst the women tended the fields. He entered his quarters and changed into more appropriate attire, then summoned his daughter, Angela, who had been waiting eagerly for the moment to arrive.

****

Angela’s constant companion, a two-year old orang-utan by the name of Yuh-Yuh, held her long, reddish-brown arms open wide demanding she be lifted.

‘No,Yuh-Yuh, not now!’

Rejected, Yuh-Yuh rolled on the wooden planked floor and clucked.