ТОП просматриваемых книг сайта:

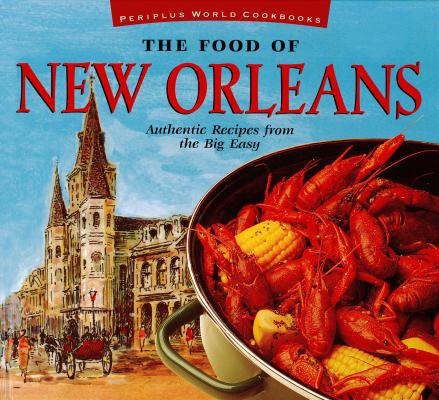

The Food of New Orleans. John DeMers

Читать онлайн.Название The Food of New Orleans

Год выпуска 0

isbn 9781462905447

Автор произведения John DeMers

Жанр Кулинария

Серия Food Of The World Cookbooks

Издательство Ingram

Today, the name Sazerac is diligently protected by the Sazerac Co., which actually licenses it to the Sazerac Bar at the Fairmont Hotel, which in turn served more than its share of the cocktails when it was the high-rolling Roosevelt.

The Hurricane (a newcomer compared with the Sazerac), made with passion-fruit flavoring, dark rum, and citrus juices, was created as a promotion at Pat O'Brien's Irish bar.

With the astronomical success of the Hurricane, the bar has even spun off a glass whose shape is recognizable anywhere—it is a footed glass, rounded at the bottom and tapering to a flared cylinder at the top. It is particularly well-known on Bourbon Street in the wee hours of the morning. Pat O's has given birth to other drinks bearing names like Cyclone, Squall, and Breeze.

Another historic favorite, the gin fizz (made of cream, gin, lemon juice, orange flower water, and egg whites) was created by Henry C. Ramos, a New Orleans bar owner who arrived in the city in 1888. At the time Ramos's Imperial Cabinet had a huge squad of bartenders, as many as thirty-five pouring out gin fizz after gin fizz during Carnival of 1915. The drink was a favorite of Louisiana governor Huey Long, who associated it with the bar at his beloved Roosevelt Hotel. When Long moved to Washington to serve in the U.S. Senate, he at first despaired of keeping the Ramos supply lines open. Eventually, the Kingfish imported his own bartender from New Orleans and made the drink, quite literally, the toast of the capital.

Along with the Sazerac, the Absinthe Suissesse and the Absinthe Frappe were the most famous New Orleans drinks associated with the namesake ingredient before its ban. Today, absinthe is typically replaced with Ojen.

A local variant on the Brandy Alexander that became a nationwide fad during Prohibition, Brandy Milk Punch, the primal version of the smoothie made of brandy, cream, sugar syrup, and egg, is great as a brunch aperitif. According to local lore, which invariably fights firewater with firewater, the Brandy Milk Punch helps cure hangovers.

We may not sip cool mint juleps on plantation verandahs, but on a hot New Orleans summer day there is nothing better than sitting on a French Quarter balcony, glass in hand, and watching the world go by.

A New Orleans Dine Around

Creole or Cajun, old or new, restaurants serve food and fantasy

by John DeMers

It is possible—even easy—to dine on history in New Orleans, both in terms of traditional recipes and in terms of restaurants still serving them in settings that exude history.

Nearly all of the city's oldest restaurants (in fact, the oldest one in America, Antoine's) are found in the French Quarter. This is where local European-recorded history began; this is where the settlement first became a city with aspirations of being the Paris of the New World.

There were a few eateries here before 1840, but Antoine's (713 St. Louis Street) is the oldest to survive into our modern day. It's unlikely that when Antoine Alciatore, then only twenty-seven, left Marseilles and opened a kind of no-frills boardinghouse on St. Louis Street, he could have foreseen what it would become.

Surely, he couldn't have foreseen the now famous dishes created at Antoine's, from oysters Rockefeller to pompano en papillote, or the presidents, movie stars, and authors who would dine within these walls. When Pope John Paul II visited New Orleans in 1988, it was Antoine's that cooked his meals.

The lacy wrought iron balconies of the French Quarter.

Tujague's (823 Decatur Street) is by most accounts New Orleans' second-oldest restaurant—and it couldn't be more different from Antoine's. It reached legendary status under a certain Madame Begue, who dished up huge wine-kissed "second breakfasts" (a prototype of today's brunch) to merchants from the nearby French Market. Today, most of Tujague's traditions remain strong, thanks to the Latter family. Do not miss the shrimp remoulade, boiled beef brisket with horseradish sauce, the hypergarlicked Chicken Bonne Femme, or the bread pudding.

Another of the older French Quarter eateries is Galatoire's (209 Bourbon Street), which made a home for itself on Bourbon Street in 1905, before any of that thoroughfare's current personality took hold.

If any restaurant here is more traditional than Antoine's, it would have to be Galatoire's, with its glittering dining room filled with high-society wave-and-wink, its veteran wait staff, and a menu taken from a Creole time capsule. What Galatoire's does, no one does better.

Henn Alciatore, maitred' in the Rex Room at Antoine's.

Chef Emeril Lagasse, though originally from the East Coast, is a celebrity in his adopted city He started at Commander's Palace and has since opened several successful restaurants of his own.

Arnaud's (813 Bienville Street) began operation in 1918 under the care of Arnaud Cazenave, a Frenchman so classy that before long he was known universally as "Count Arnaud." (He wasn't a count, in France or anywhere else—except maybe along Bienville Street!) With help from his daughter Germaine Wells and Archie Casbarian in the 1970s, Arnaud's today is as wonderful as anyone can remember it. The Shrimp Arnaud and Trout Meunière are musts here, and the bread pudding is the best.

Brennan's (417 Royal Street), while most famous for serving egg after egg after egg with too many cocktails at breakfast, is an insufficiently recognized gem for lunch or dinner. Many Creole classics were invented here, which makes Brennan's not only an interesting tourist spot but a part of history.

Commander's Palace (1403 Washington Avenue) in the Garden District remains a bridge between the Old World and the New, having reinvigorated traditional Creole cooking through the years with such well-known chefs de cuisine as Paul Prudhomme and Emeril Lagasse. With Jamie Shannon running the kitchen now, the Brennan family has every right to be confident that Commander's selection as a 1996 James Beard Award winner is no flash in the pan.

Near Commander's Palace, JoAnn Clevenger and chef Richard Benz keep creating wonderful things at the Upperline (1413 Upperline Street). In particular, Upperline is known for its "festival fetish," producing such events as a garlic festival, a duck festival, and festivals about whatever big event is in town.

A bit farther away from the maddening crowd, there's Brigtsen's (723 Dante Street), in the River-bend section. Just past its tenth anniversary, Brigtsen's and its chef-owner, Frank Brigtsen, put one of the best spins going on creative Creole-Cajun flavors. Whatever Brigtsen is doing with rabbit, don't let it get away.

Closer to downtown, the born-again Warehouse District has become a true restaurant row. Leading the renaissance has been Emeril's (800 Tchoupitoulas Street), established by former Brennan's chef Lagasse and reflecting his open-ended, highly personal style of cooking. If you sit at Emeril's food bar, you can even watch him cook.

Also in the Warehouse District (sometimes called the Arts District) you'll find Mike's on the Avenue (628 St. Charles Avenue), the restaurant that has done the most to convince locals that they can eat any cuisine on earth-all on the same plate, if they want to. Chef Mike Fennelly came to the city from New York by way of Santa Fe, and he offers the best of Thai-Southwestern-Mediterranean food. Mike's is chic, bright, airy, and deliciously unforgettable.

Lest you think a chef's departure is the worst thing in the world, you can walk around the corner and try the Grill Room at the Windsor Court (300 Gravier Street). Under Jeff Tunks's Asian-influenced hand, there's been no dramatic change of direction—it's just some of the world's best ingredients served in the city's most luxurious dining space.